I am prepared to risk it all by admitting that I enjoyed Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. There it is. The 2008 film didn’t get the best reception because of its overdone CGI and unlikeable characters. But the storyline — centered on a mysterious, elongated skull from Peru — grabbed me.

Crystal skulls are some of the most fascinating, strange mysteries out there. They arrived on the archaeological scene in the 19th century, most without stories or context attached. For many years, no one knew who made them or why. But in the early 2000s, they were proven to be fakes, so why do museums still bother to display them?

Where it all began

Our story begins in January 1924. The sound of cutting, cracking and enthusiastic voices interrupted the stillness of the jungle in British Honduras (now Belize). A group of local Mayan descendants, a teenage girl and her dear Papa were searching for something. The father, Frederick Mitchell-Hedges, was on a mission to fulfill his dream of becoming a world-renowned archaeologist after leaving his Wall Street job. And Anna, his protege and adopted daughter, wanted to make a name for herself in the field as well.

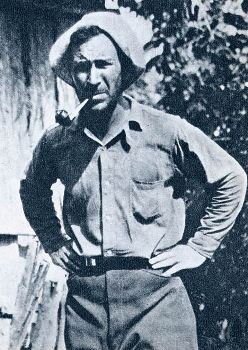

Frederick Mitchell-Hedges.

Somewhere in the bush was a lost city called Lubaantun, or “the place of fallen stones” in ancient Yucatek Maya. The site was occupied from 730 to 890 AD. At first, it did not look like much, with stones scattered everywhere and the ruins of pyramids. But it would become the epicenter of a phenomenon that took the world by storm.

On finding the ruins, young Anna took this chance to explore for herself without the supervision of her father. While peering through a crack in a sunken temple, she saw a small shiny object glistening in the sliver of sunlight. Risking the unstable ruins, she ventured into the dark and uncovered a skull. Not just any skull. Rather, it was a life-size skull of pure, clear quartz (13cm high, 18cm long, and 13cm wide.) This was her ticket to fame, and the skull soon became known as the Mitchell-Hedges skull.

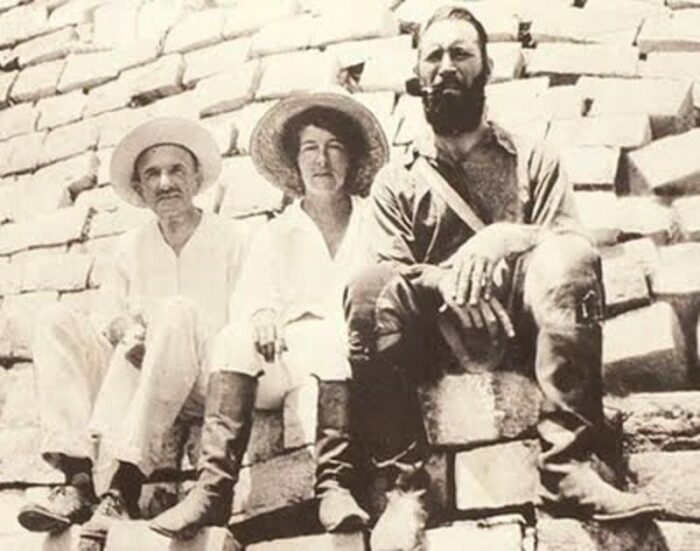

Frederick and Anna Mitchell-Hedges. Photo: The History Blog

A supernatural object?

The discovery overjoyed their Mayan guides. Supposedly, it had been missing for centuries and was a big part of their heritage. According to local legends, the skull was a crystallized likeness of a beloved and powerful high priest. To preserve his powers, they crafted the skull after him, believing that his essence could be transferred into the skull. Those in possession of the skull could will death on his enemies.

The most important rule was, don’t look into its eyes. It will drive you mad or even kill you. Curiously, the locals gifted Frederick and Anna the skull as a thank-you. Since then, the skull has been credited by New Agers, shamans, and UFO enthusiasts as the key to hidden knowledge and unlocked psychic abilities. They nicknamed it the Skull of Doom.

Skulls were not uncommon in Mesoamerican cultures. They played a big role in the religious, social, and artistic lives of the Maya and Aztecs. It symbolized both life and death and was mostly associated with human sacrifice, rebirth, and appeasing the gods. Skulls continue to be a major symbol of Mexican cultural practices.

An art restorer named Frank Dorland studied the skull to estimate its value. He determined it was thousands of years old, even older than the site itself. He believed it was carved out of a chunk of quartz, rubbed together, shaped, sanded down, and polished with diamonds for 150-300 years, the time it would take to make it so clear.

Anna Mitchell Hedges later in life, with her precious crystal skull. Photo: Crystalskull.com

Where it gets weird

You would think that such a discovery would have made Anna and Frederick famous as soon as they got back to civilization. Wrong. It wasn’t until the 1940s that the skull went public. So why wait? Unless the pair was hiding something.

After her father died in 1959, Anna went into full-on marketing mode. She began to promote events in which patrons could — for $5 admission — view the skull, feel its power, and hear about that life-changing find in the jungles of Belize. First red flag! The 1960s and 1970s were the perfect time to start such a venture, as spirituality and New Age exploration were at their peak.

If you check out Frederick’s autobiography titled Danger My Ally, you’ll see that it does not mention Anna’s discovery at all. You’d think that Frederick would have raved about the skull or at least made its discovery public. Rather, there is only mention of acquiring a skull, saying:

It is at least 3,600 years old and according to legend was used by the High Priest of the Maya when performing esoteric rights. When the High Priest willed death, with the help of the skull, death inevitably followed. It has been described as the embodiment of evil. I do not wish to try and explain this phenomenon….

No mention

Why is there no mention of Anna and her find?

Let’s look at Frederick Mitchell-Hedges. He was a restless man working in the finance sector, trying to build wealth for himself in London and Wall Street in New York City. Deep down, however, he yearned to be an archaeologist, particularly one who was well respected in the academic community.

Mitchell-Hedges left his well-paying job after saving up £4000 and became a full-time explorer. He had somewhat of a reputation, getting into relationships with wealthy women so he had access to funding for his expeditions. He even claimed that he found artifacts from Atlantis. Surely, such a person would have spoken about this crystal skull.

However, records from the Sotheby’s, published in the British journal Man, show a skull — reputedly an artifact from Mexico — went up for auction in 1936. The buyer was none other than Mitchell-Hodges. It seemed that he bought the skull, and the whole story of its serendipitous discovery was apocryphal.

The truth comes out

When Anna was confronted with this information, she stated that her father ran into financial trouble and received a loan from an art dealer named Sydney Burney after Mitchell-Hedges gave him the skull as collateral. However, Burney double-crossed him and put it up for auction.

Yet in a letter to his brother in 1943, Mitchell-Hedges suggests that the crystal skull was, in fact, a purchase:

The “Collection” grows and grows and grows. You possibly saw in the papers that I acquired that amazing Crystal Skull that was formerly in the “Sydney Burney Collection.” It is fashioned from a single block of transparent rock crystal, exactly life-size; scientists put the date at pre-1800 BC, and they estimate it took five generations passing from father to son, to complete. It is anthropologically perfect in every detail, a superb piece of craftsmanship. There is only one other in the world known like it, which is in the British Museum and it is acknowledged to be not so fine as this.

The matter was eventually put to rest in the 1970s when curious researchers from Hewlett-Packard’s laboratories took up Dorland’s suggestion to analyze it. Though the lab’s technology could not determine its age, it did find signs of metal drills used on its teeth. Anna did not hesitate to take the skull back and refuse any more scrutiny.

Anna’s later years

Anna married a man named Bill Homman and they toured with the skull until she died in 2007. Homman became its owner and he took the skull to the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. for analysis. However, it did not have the answers he was looking for.

Jane Walsh, the main researcher behind the tests, found some interesting details. X-ray and electron microscope scans revealed polishing and tool marks consistent with 19th and 20th-century techniques, particularly those associated with rotary tools and abrasives, most likely with a diamond head. Therefore, this was most likely made in the 1930s.

Smithsonian Skull. Photo: James Di Loreto/NMNH

Ancient civilizations, including the Maya and Aztecs, lacked the technology to carve such precise and smooth shapes from hard quartz. The fact that some skulls displayed features like perfectly symmetrical teeth suggested they were produced much more recently than claimed. Yet…this skull is on display for its expert craftsmanship rather than its historical accuracy.

It’s now apparent that the elaborate tale of Anne finding the skull deep in a cave in a jungle in Belize was made up from start to finish. The inconsistencies in her story, conveniently bending the details of her father’s purchase of the skull from an art dealer in London in the 1940s and the lack of records of having been in Belize in 1924 in the first place all point to an elaborate con job.

Other skulls turn up

The Mitchell-Hedges Skull is not the first such quasi-treasure. They’ve been around since the 1800s. The British Museum’s crystal skull, often referred to as the Mittler Skull, was acquired in 1897 from a collector named Eugene Boban.

A French antiquities dealer, Boban claimed that it had been discovered in Mexico. Most likely, he lied about its age to get more sales. He said it was found in an ancient Aztec or Mayan tomb. Others linked it to the broader lore surrounding pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures. However, the lack of solid provenance and the skull’s highly polished surface has led many researchers to question its authenticity as a genuine artifact.

British Museum skull craftsmanship. Photo: Rafał Chałgasiewicz/Wikimedia Commons

When Dr Jane Walsh received another skull in an anonymous package, she couldn’t help but analyze it. This one was not life-size but very large, around 31 pounds. It was not an accurate human skull but had more decorative embellishments. She enlisted the help of British Museum scientist Margaret Sax to help her compare the two skulls.

After rigorous tests, she said:

British Museum scientist Margaret Sax and I examined the British Museum and Smithsonian skulls under light and scanning electron microscope and conclusively determined that they were carved with relatively modern lapidary equipment which were unavailable to pre-Columbian Mesoamerican carvers…

The British Museum skull was worked with hard abrasives such as corundum or diamond, whereas X-ray diffraction revealed traces of carborundum (SiC), a hard modern synthetic abrasive, on the Smithsonian skull. Investigation of fluid and solid inclusions in the quartz of the British Museum skull, using microscopy and Raman spectroscopy, shows that the material formed in a mesothermal metamorphic environment equivalent to greenschist facies. This suggests that the quartz was obtained from Brazil or Madagascar, areas far outside pre-Columbian trade networks.

Conclusion

So, where does this leave us? They’re fake, yes. But you can’t help but admire the craftsmanship and beauty of the pieces. In a way, its creators got what they wanted: fame of a sort.