In late November, Cyclone Senyar tore across Indonesia, dumping an incredible meter of rain on the island of Sumatra. Over four days, floods and landslides killed over 1,000 people and displaced hundreds of thousands of others. It was also a catastrophe for the rarest great ape on the planet.

The Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) was only discovered in 1997 and recognized as a distinct species (separate from Bornean and Sumatran orangutans) in 2017. With only three known populations, all in the Batang Toru region, and fewer than 800 individuals surviving overall, they are already critically endangered.

Deforestation and habitat fragmentation from mining, logging, hydropower projects, and the palm oil industry have severely impacted all orangutans, including these. Now, researchers believe the cyclone has pushed them closer to extinction.

“It’s a total disaster,” Erik Meijard, lead author of the new study, told The Guardian.

He called the disaster an “extinction-level disturbance” for the species. The great apes only reproduce every six to nine years. Even a seemingly tiny loss has a huge impact on the species’ survival chances.

A Tapanuli orangutan skeleton found in the mud in North Sumatra. Photo: Decky Chandra

Dozens of orangutans perished

Scientists estimate that between 33 and 54 Tapanuli orangutans died from the cyclone. That is a significant proportion of the small population. Earlier research suggested that just a one percent decline in the population would likely cause the orangutans to go extinct in the near future.

Rescue teams searching for human casualties took photos of one particular Tapanuli orangutan that perished in the cyclone.

“What struck me is that all the flesh had been ripped off the face,” Meijard told the BBC. “If a few hectares of forest come down in massive landslides, even powerful orangutans are helpless and just get mangled.”

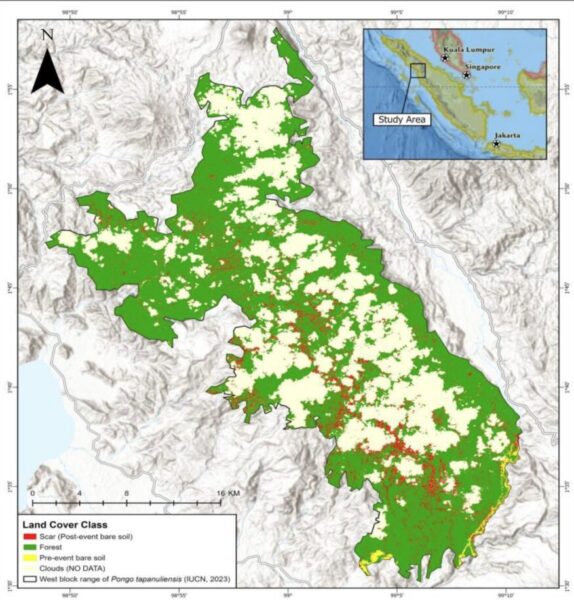

By analyzing satellite imagery, they were able to deduce that the flash floods and mudslides swept away almost 4,000 hectares of forest and damaged another 2,500 hectares.

Cloud cover made it impossible to see the full extent of the destruction. But some sections of forest up to 100 meters wide and over a kilometer long were destroyed.

“I have never seen anything like this before during my 20 years of monitoring deforestation in Indonesia,” remote-sensing expert and conservationist David Gaveau told The Guardian.

Map showing the scars created by the flooding and landslides in the Batang Toru ecosystem. Image: Meijaard et al., 2025

Lost habitat

Aside from the actual deaths, researchers are worried about the lasting effects on the habitat. The satellite imagery shows enormous scars across the Batang Toru forest. Its canopies once provided food, shelter, and travel routes for the orangutans.

“The rainfall was intense. If you lose your fruit, you lose your flowers; there will be a significant reduction in habitat quality,” Meijaard said.

Deforestation and habitat degradation made the destruction a lot worse. Logging, plantations, mining, and infrastructure projects have made the land less able to absorb intense rainfall. Landslides and flooding are thus more severe than they might have been.

Indonesia’s environment ministry has stopped all private-sector activity in the Batang Toru region indefinitely.