Dane Steadman squeezed in some time between his flights to Patagonia to talk to ExplorersWeb about the recent climb he did up 6,667m Yashkuk Sar with fellow Americans Cody Winckler and August Franzen. The 2,000m-long route up a difficult and aesthetic spur in Pakistan might be one of the best expeditions of 2024.

Closed until this year

At first sight, it looks surprising that such a stunning peak had not been climbed yet. But as Steadman explained, there were at least two good reasons.

First, the Charpusan Valley in Pakistan’s Hunza region had been closed to foreign teams for the last 15 years.

“I believe this was the first year they re-opened it,” Steadman said.

The route is also highly difficult.

“It used to be open [in the past],” said Steadman. “A couple of teams went with the intention of climbing Yashkuk, according to the locals, but ended up trying/climbing easier peaks. My guess is that’s because from the north side, Yashkuk is either dangerous (seracs crown almost the whole north face) or difficult (the buttress we climbed is fairly steep and rocky).”

Choosing the goal

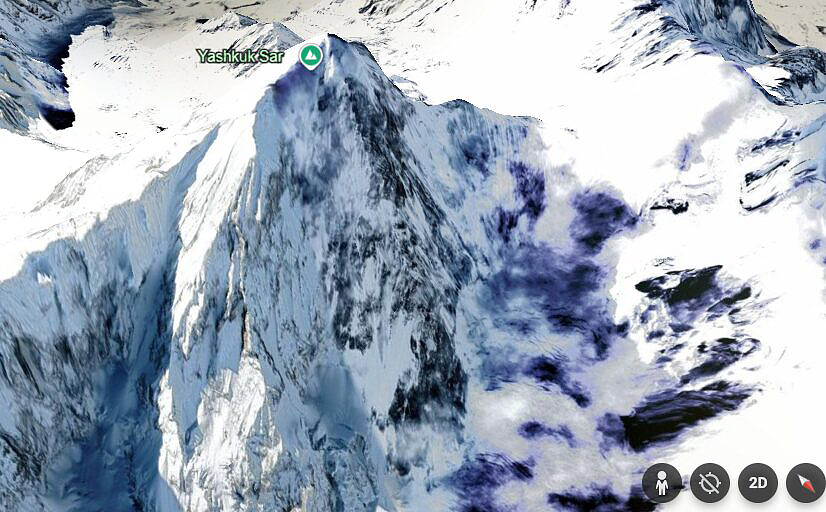

Yashkuk Sar on Google Earth, with the north buttress to the right.

Yashkuk Sar seemed to tick all the boxes, and it had finally opened to climbing. Steadman, Franzen, and Winckler started to make plans last November.

“From the few photos of the face we’d been able to find, we had identified the north buttress as our targeted line of ascent,” he explained. “It was beautiful and seemed safe from the seracs hanging over the rest of the face.”

On the ground

Photo: Dane Steadman

The climbers acclimatized by climbing Sax Sar, a 6,200m peak north of Yashkuk. Sax Sar had been climbed once before, and the Americans bagged a new route. Then they went for Yashkuk in a single, alpine-style push.

On the buttress

Among the ice runnels. Photo: Dane Steadman

“Partway up one of the big ice runnels, we traversed out left to an ice arete via a difficult snowy slab pitch. Here, we made our first bivy using a Russian ice hammock about 1,000m up the face.”

On the second day, the team climbed 400m on moderately difficult ice to a narrow ridge, where they set up their second bivouac on a flattened cornice.

“Day three started with a rappel down off the ridge to the other side, the only aid of the route,” Steadman recalled. “Then [we went] up an ice arete for a couple hundred meters to the base of the headwall. We finished the day with two tricky pitches up snowy gneiss that was either smooth and compact or heavily fractured.”

The spectacular third bivouac. Photo: Dane Steadman

They set their third bivy atop a wild snow mushroom on another arete at about 6,200m. The tent hung precariously over the edge on both sides.

“The final day started with three difficult mixed pitches up to M6, then two traversing pitches back right through a forest of snow mushrooms and along a marble band to the crux ice pitch, overhanging AI5+, that led to the top of the headwall,” Steadman said.

The top of the headwall was not the end of the climb. The three continued along the summit ridge, slowly plowing through deep snow. They couldn’t reach the top that day. Instead, they made another bivouac in a crevasse just below the summit.

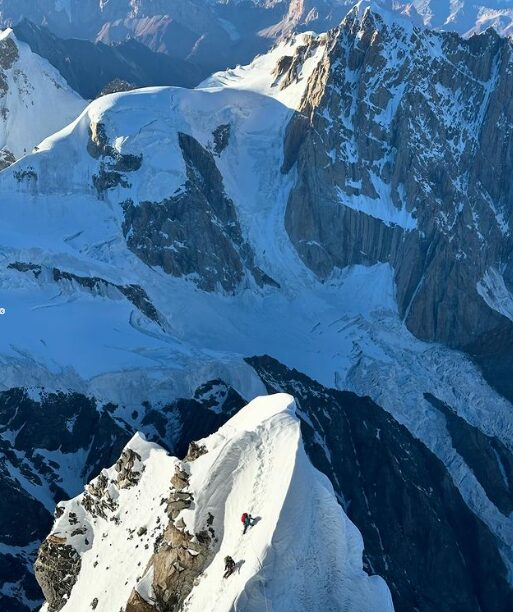

A section of the ridge, as seen from above. Photo: Dane Steadman

“We topped out early the next morning on a beautiful day, then began descending the west couloir,” Steadman explained.

The team made 10 rappels down, and then they had to climb up again over the west ridge. Finally, they again rappelled and downclimbed the far western edge of the northwest face of Yashkuk.

“We reached the glacier around 4 pm and got back to advanced base camp around 8 pm.”

The team called their 2,000m route the Tiger Lily Buttress and graded its difficulty as AI5+ M6 plus A0 for the rappel. Steadman had obtained a Cutting Edge Grant for the climb.

On mixed terrain. Photo: Dane Steadman

Last year, Steadman — a professional climber and mountain guide from Wyoming — used another Cutting Edge grant to set a new route on Pik Alpinist in Kyrgyzstan with partners Jared Vilhauer and Seth Timpano.