A single asteroid descended without warning to end the reign of dinosaurs, at the peak of their size and strength. It’s too cinematic an image, too archetypal a story, to possibly be true, isn’t it? For decades, scientists have questioned this simplistic narrative of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction, or K-Pg event.

For much of the 2000s, researchers investigated the additional role of volcanic activity, as well as sea level and climate change, which preceded the famous impact. Maybe it’s too frightening to imagine that a single chunk of rock in the wrong place could wipe out between 75% and 80% of species on Earth.

But emerging research in the last few years suggests the old theory was right, after all. A new study funded by the National Science Foundation found that dinosaurs in New Mexico had healthy, diverse populations in the final days before a 10km-wide asteroid struck the Yucatán Peninsula.

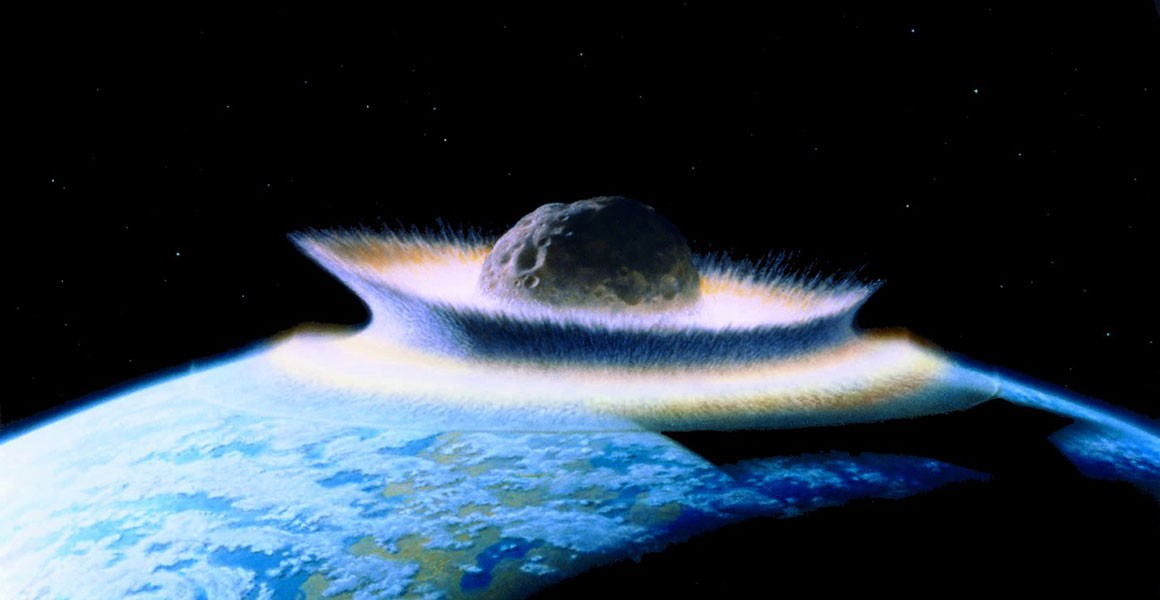

I think we can all agree that this looks like something that would be bad for the environment. Photo: NASA Image and Video Library

Searching for boundary-dwellers

The boundary between dinosaur times and post-dinosaur times is actually a physical line imprinted on the Earth. The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary (like me, you may have learned as a child that it was the Cretaceous–Tertiary (K–T) boundary, but this term is no longer in use), is a thin band of iridium-rich rock which formed approximately 66 million years ago.

The idea that an impact event caused this layer of iridium, and that this event also killed off the dinosaurs, was first proposed by father-son physicist-geologist team Luis and Walter Alvarez in 1980. To study the final Cretaceous ecosystems, paleontologists look at geological formations formed right below this boundary line. But as with all things, simple rules like this get complicated in practice.

In the Ojo Alamo rock formation in New Mexico, several chunks, called members, from different eras divide the rock. The Naashoibito Member is from the Maastrichtian age. This age included the final days of the Cretaceous from 72 to 66 million years ago. However, confirming the date of the fossils within these formations has been a sticky subject, as the layers fold in on each other and overlap.

To prove that the fossils they were looking at were really from the late Maastrichtian, the National Science Foundation researchers had to develop a new model for how the layers were deposited. Once they had a better picture of what they were sampling, they could model a snapshot of the late Maastrichtian.

The K-Pg boundary line can be found in sites all over the world. Photo: U.S. Geological Survey

The titans of the latter days

What they found was a total upending of previous models. Popular understanding went that species diversity had peaked in the earlier Campanian era and declined as the Maastrichtian went on. When the asteroid hit, so the story went, dinosaurs were less diverse and less healthy than they had been.

But the researchers, led by Andrew G. Flynn of New Mexico State University, found this wasn’t the case at all. The fossil specimens in this late Maastrichtian group were not abnormal or smaller than the Campanians. The models showed healthy species diversity across different sizes, diets, and lifestyles.

Rather than a slow population collapse, the late Maastrichtian was a time of flourishing speciation and high regional diversity. And then the asteroid hit.