A team of genetics researchers has sequenced the genomes of Greenland sled dogs, or qimmeq (plural qimmit), both living and dead. Their results shed light on both the development of this breed and Greenland’s murky human history.

Qimmit are the oldest dog breed, and the Greenland government takes their genetic conservation seriously: no other dogs are allowed above the Arctic Circle. But interbreeding is not the only threat to their survival.

Qimmit are tough, working dogs, and they regularly injure or even kill humans, particularly children. For a long time, their usefulness outweighed any danger; they were a vital part of Arctic travel, and their intense pack-bonding and high drive were a feature, not a bug. But snowmobiles have changed everything. In 2002, there were around 25,000 qimmit in Greenland. In 2020, there were only 13,000.

New research, published in the journal Science, began as a quest to preserve the genetic information of the qimmeq before it’s too late.

In the northwestern village of Qaanaaq, dogs outnumber people. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Qimmeq DNA challenges timeline of Greenlandic settlement

Traditional scholarship places the Inuit settlement of Greenland at about 1200 CE. They would have joined the preexisting Dorset culture, which dropped out of the archaeological record several centuries later, as well as the Norse.

The Norse first ventured to Greenland in 985, when Erik the Red made contact with the “Skraelings” of the southeastern coast. They maintained a presence on the island until sometime in the 15th century. In the 18th century, Denmark embarked on a mission to recolonize Greenland, although first they had to find it again. Greenland has remained a Danish colony since.

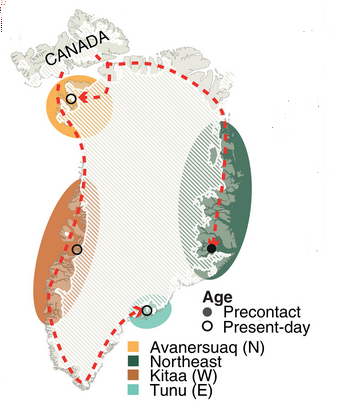

By analyzing the remains of qimmit before Danish colonization, the team of geneticists challenged this narrative. Their models suggest that qimmit diverged from earlier species of sled dog 1,164 years ago — over a hundred years before Erik the Red’s arrival. In the centuries afterward, different regional variations diverged from one another within Greenland.

Either the qimmit were migrating on their own, or the Inuit arrived in Greenland much earlier than previously thought.

Qimmeq DNA sampling allowed researchers to build a timeline of Inuit settlement in Greenland. Photo: Feuerborn et al 2025

Where did the first Greenlandic Inuit come from?

Another interesting facet of the new research is the qimmeq’s closest genetic relative. Rather than a modern husky or samoyed, qimmit shares the most DNA with the remnants of a dog from Alaska. Found near Teshekpuk Lake, this dog was alive about 3,700 years ago.

Finding the most similar genetics in Alaska rather than in Canada indicates that the ancestors of the Inuit moved rapidly from Alaska toward the eastern coast of Canada. The next closest relative of the qimmeq is a 4,000-year-old dog from Port-au-Choix in Newfoundland and Labrador.

The qimmeq’s closest genetic relative is a 3,700-year-old dog from Teshekpuk Lake in Alaska. Photo: Teshekpuk Lake Observatory

The shadowy history of northeastern Greenland

The dogs’ DNA also adds to the scant archaeological record of northeastern Greenland.

In 1823, an up-and-coming captain in the British Navy named Douglas Clavering received an assignment: to escort his friend, astronomer Edward Sabine, to the Arctic Circle. Sabine, a veteran of both the Ross and Parry Arctic expeditions, was engaged in a quest to measure the shape of the Earth using a pendulum. The period of a pendulum depends on gravity. Therefore, if the Earth bulges at the equator, the pendulum will have different periods at different latitudes.

But while engaged in his scientific ventures, Clavering twice encountered the same group of 12 Inuit. This was the last time any Inuit were confirmed to live in the northeast of Greenland before resettlement in the 19th century.

Oral history preserves stories of Inuit migration toward the southeastern coast of Greenland from the north over multiple centuries before Clavering’s encounter. But the motives of this migration, along with when exactly the Inuit finally vacated the northeast, are unclear.

Archaeological evidence and oral tradition form the bedrock of pre-Danish Greenlandic history. Professor Asta Mønsted, the archaeologist excavating here, is a leading voice in the field of Greenlandic Inuit history. Photo: Niels Mønsted

Clues from Qimmeq DNA

The new research places the first concrete estimate on the settlement of northeast Greenland: 1,146 years ago. This suggests that the Inuit settlers of Greenland moved from the northwest to the northeast within only a generation or two.

The pre-Danish northeastern qimmit is the most distinct regional population by far. Despite the rapid settlement of the northeast, once they were there, the northeastern Inuit didn’t seem to intermingle with other communities in Greenland. Trade networks connected the whole west coast, but qimmit DNA suggests they did not venture east.

This supports one particular theory of the abandonment of the northeast: isolation. Archaeologists have suggested that among the many challenges faced by inhabitants of the northeast, the death knell may have been the nigh-insurmountable distance between their villages and any other communities. When the Little Ice Age struck in the early modern era, they would have had no allies. Migration may have been their only chance of survival.

A new tool for human history

In the absence of a historical record, the genetic analysis of companion animals can trace human migrations. Qimmit present a unique case because of their genetic preservation to the modern day.

Outside of Greenland, many dog breeds face serious genetic ailments because of inbreeding. Several breeds are now unable to give live birth. Meanwhile, the qimmeq has stayed healthy despite modern, artificial isolation and over a thousand years of natural isolation. This is a testament to the care with which its human companions have treated it for over a millennium.