Humanity’s closest relatives, both extinct, are the Neanderthals and the Denisovans. The second group, who lived alongside both humans and Neanderthals, were only discovered in 2008. They lived across Asia and Siberia, and may have passed on increased altitude tolerance to Tibetan and Nepalese people, who carry around 2% Denisovan DNA.

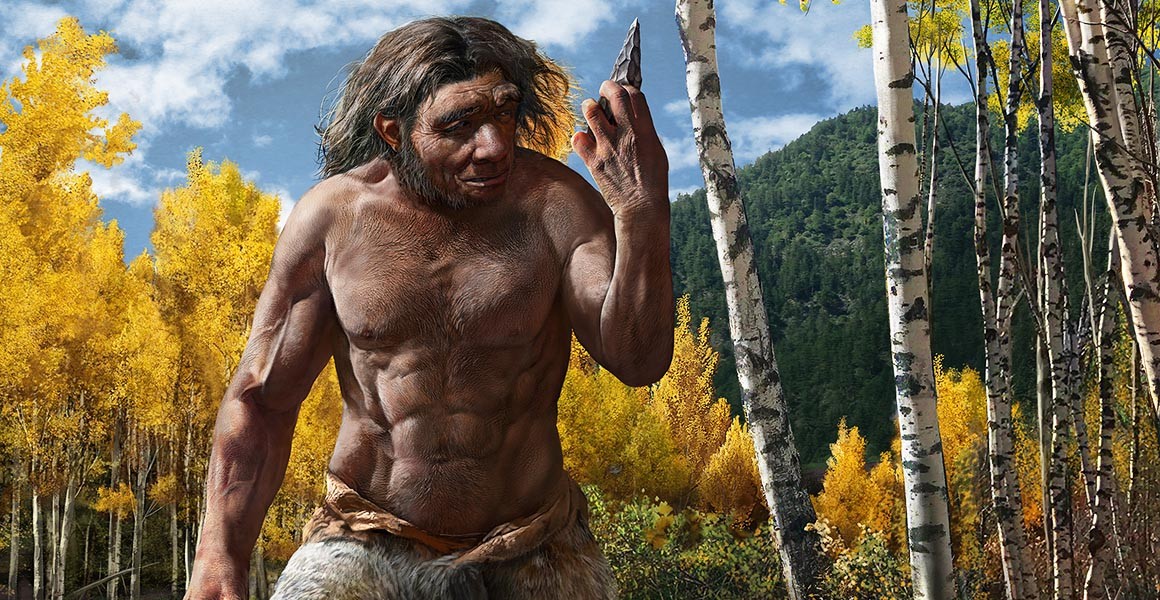

The Denisovans were sophisticated tool users, crafting stone axes as well as decorative objects. They spent at least some of their lives in caves, where the remains and artifacts have been found. We learned all this about our lost cousins from recovered artifacts, loose teeth and slivers of bone. Until now, we hadn’t found a single Denisovan skull.

Or, rather, we didn’t think we’d found one. Turns out, one was found in the 1930s.

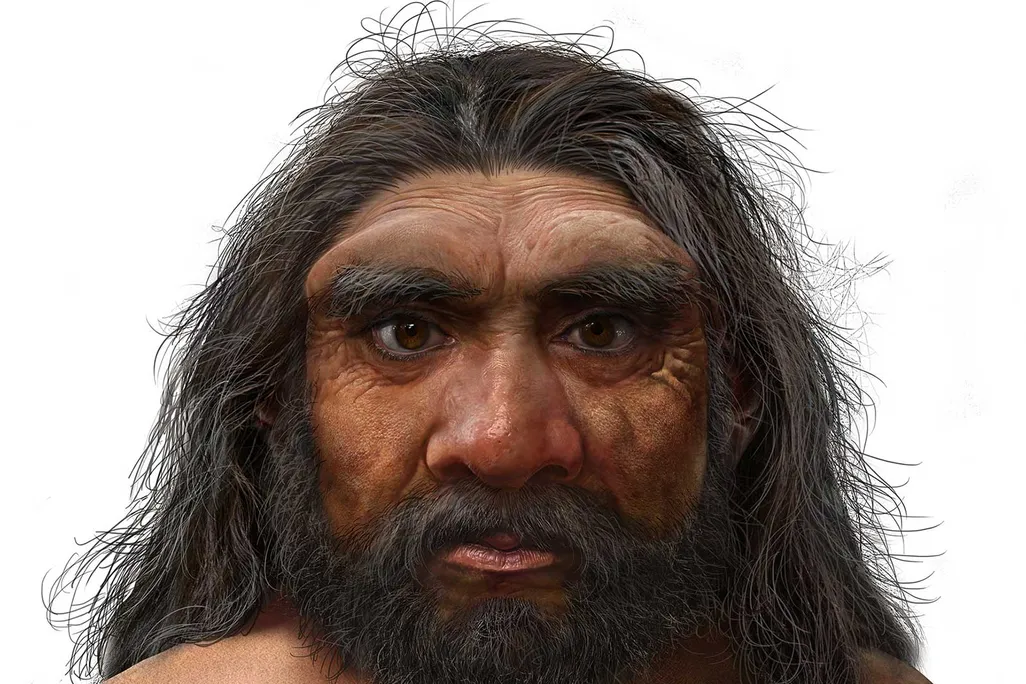

An artist’s recreation of the Dragon Man in his natural environment imagines him insanely ripped, with kind eyes. Photo: Chuang Zhao

A century of mistaken identity

In 1933, construction of a bridge over northeast China’s Songhua River churned up old sediment. In the sediment was a skull. Someone, presumably a worker, took the skull home and kept it safe. The family of farmers held onto it for three generations, passing it down.

Then in 2018, a farmer decided to donate the old family skull to Hebei GEO University. It was immediately subjected to a battery of examinations resulting in three different studies. One dated it to 146,000 years old; another pegged it at 138,000 years; a third, at 309,000 years old.

More intriguingly, they compared it to other known hominid skulls and found no match. The cranium was larger than any other hominid, suggesting a brain size in line with our own. But other features more closely resembled earlier human ancestors: heavy, jutting brows and large, prominent teeth with squarish eye sockets.

He must, they decided, be a new species. The “Dragon Man,” as he was being called, after the Songhua River’s associations with them, was Homo longi.

But a pair of new studies turned the Homo longi theory on its cranium.

The skull of the “Dragon Man” is the first Denisovan cranium we’ve found. Photo: Ni et al

Proteins and the family tree

Researchers from Chinese, German, and American universities worked together to extract genetic information from the Dragon Man skull, also called the Harbin cranium. They had noticed similar large teeth on both the Harbin cranium and the Xiahe mandible, a jawbone found on the edge of the Tibetan plateau.

In a previous study, researchers identified the Xiahe mandible as the remains of a Denisovan. It was the first hominid remains found using proteomic analysis, a technique that matches unique proteins. If the mandible was Denisovan, researchers wondered, then the matching Harbin cranium might be, too.

One of our closest cousins, the Denisovans left artifacts such as stone tools and decorative objects. The items here, carved from bone and stone, came from a Denisovan cave. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But the Dragon Man wouldn’t give up his secrets easily. They tried to find preserved DNA in the bone and then in a tooth, but with remains this old, it’s nearly impossible. Finally, they turned to dental calculus — calcified plaque. Dental calculus is bad for your gum health but good for preserving DNA.

And there, after cleaning, converting, and sequencing, they found what they needed. Researchers isolated pieces of mitochondrial DNA, which they could match against previous Denisovan genetic profiles. It was a match. Specifically, a match for the older Denisovans, likely before they began interbreeding with both humans and Neanderthals.

Now that we have a confirmed Denisovan skull, the studies’ authors hope more unidentified hominid fossils can be identified as Denisovan. A particularly well-preserved hominid cranium from the Shaanxi province of China may turn out to be the second Denisovan skull.