When climate journalist Alec Luhn found himself stranded in the Norwegian mountains with a broken leg this summer, he resorted to desperate measures, drinking his own urine, eating moss, and even sipping blood from a popped blister. He’s not alone in such extreme acts. Aaron Ralston, the hiker who famously amputated his own arm to escape a boulder, reportedly also drank urine. And TV adventurer Bear Grylls has turned the practice into a signature move during his staged survival challenges.

Does this desperate act of drinking your own pee actually work, or is it just a survival myth that refuses to die?

Stories like Alec Luhn’s can make it seem as if drinking urine is a legitimate survival tactic when water runs out. But these survivors may have lived despite their choices, not because of them. We rarely hear about the countless others who tried similar methods and didn’t make it.

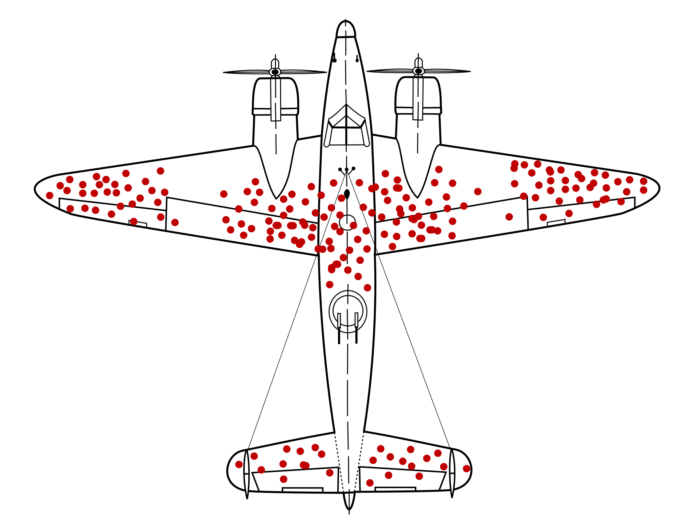

This selective storytelling is an example of survivorship bias, a tendency to focus on the rare success stories while overlooking the many failures that never make the headlines.

A World War II analysis illustrating survivorship bias: red dots mark bullet holes on Allied aircraft that safely returned from missions, showing where they could sustain damage and still make it home. Military analysts initially thought these areas needed reinforcement, but statistician Abraham Wald pointed out the flaw: Planes that did not return were likely hit elsewhere. His insight led to reinforcing the untouched sections instead. Photo: Wikipedia

Drinking urine is not new

There has been documented use (drinking, applying it to skin or gums) of human or animal urine dating back to ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, though modern science provides little to no evidence that it offers any real health benefits. In fact, research suggests that drinking urine can pose significant health risks rather than deliver healing effects.

Ancient traditions often attributed remarkable powers to urine. In Ayurvedic medicine, it was thought to treat ailments such as allergies, digestive issues, skin aging, and even cancer.

Mixed martial artist Kyoto Machida has been known to drink his own urine. Photo: Marcelo Alonso/Sherdog.com

The Roman poet Catullus reportedly believed urine could whiten teeth, likely because of its high ammonia content. Before the invention of glucose test strips, physicians once tasted urine to detect sweetness, an early and rather unpleasant method of diagnosing diabetes.

Surprisingly, “urine therapy” continues to this day, with celebrities and even NFL players and boxers chugging on their own waste fluids.

What about survival scenarios?

When stranded without water and with only a bit of food (a minor source of hydration), survival time is uncertain. Depending on hydration levels, the environment, and the amount of physical activity, a person may last only three to seven days without water.

Yet many people in desperate situations turn to drinking their own urine within a few days. In 2017, for example, Mick Ohman survived a mere two days stranded in the Arizona desert before resorting to his own urine after running out of water and beer.

There’s a certain logic to drinking urine early, when it’s about 95% water and 5% waste like urea. But even fresh urine contains small amounts of bacteria such as E. coli, which can cause illness. Filtering with a hiking water filter might reduce bacteria, but each time urine passes through the body, it becomes more concentrated with salts and waste, increasing strain on the kidneys.

Fresh urine in a lightweight bottle. Photo: Ash Routen

Like seawater, repeatedly drinking urine backfires: The body loses more water flushing out waste products than it gains. The result can be worsening dehydration, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and dangerous electrolyte imbalances.

Professor Mike Tipton, an expert in human physiology and survival at the University of Portsmouth in the UK, advises against turning to urine for hydration.

“You should also not drink urine in this [a survival] situation, because it will also contribute to salt building up in your body. The second important factor is to conserve body fluid.

The body of a 75kg person contains nearly 50 liters of water, and in a survival situation where dehydration is your greatest threat, conserving this water is crucial.

The body helps. With a body fluid loss of 1% of body weight and consequent decrease in blood volume and increase in salt concentration, the body increases the production of the anti-diuretic hormone that lowers urine production by the kidneys.

You can provoke this response by drinking nothing in the first 24 hours of a survival voyage.

At the same time, it is important to do as little as possible. Try to minimize heat production by the body, which will mean less sweating.

In short, by the time you’re dehydrated enough to consider drinking urine, the urine will be so concentrated that it’s just too salty. Then drinking your own pee will more likely harm than help.

What to do instead

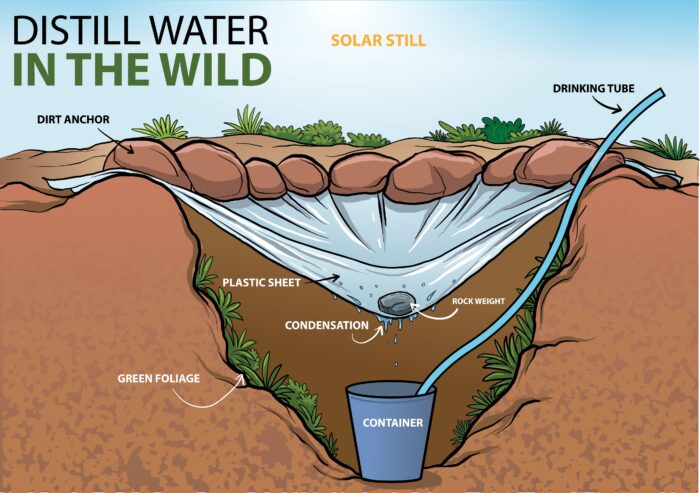

When your water bottle runs dry, there are smarter moves than sipping urine. A solar still is one of the oldest and simplest survival hacks: dig a shallow pit, drop a cup in the center, cover it with plastic, and weigh the middle with a rock. The sun does the rest by evaporating moisture from soil or plants and condensing it into clean, drinkable drops. It won’t fill a bottle fast, but it could keep you alive when every drop counts.

Illustration: Shutterstock

There are other tricks, too. Wring dew from grass with a T-shirt at sunrise, catch rainwater in anything that holds shape, or pull moisture off leaves with a plastic bag tied around a branch.

Assuming you have a plastic bag in your survival situation, tying it around a desert plant, like this camel prickle in Turkmenistan, can generate some water from condensation. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

In the rainforest, vines can drip surprisingly clean water, while in coastal zones, seawater can be evaporated and condensed using makeshift setups. Of course, the best move isn’t to move at all. Find shade, slow down, and let your body hold onto the water it’s got. If you must travel, travel at night, avoiding the sun during the day by digging a pit and lying in it, if no other shade is available.

During a simulated desert survival situation, this man dug a pit in the sand with his hands for shade. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko