Recent discoveries have shown that brightly colored crests and eye-catching patterns adorned many dinosaurs. Meanwhile, our earliest mammalian ancestors survived these flamboyant predators by being as drab as possible.

The first prehistoric mammals were small, rodent-like creatures designed to hide from their bigger, more spectacular neighbors. A new study found that their coloration reflected this lifestyle.

An artist’s recreation of ‘A. Fustus’ and its dark, grey-brown fur. Photo: Chuang Zhao and Ruoshuang Li

How do you identify 100-million-year-old colors?

Melanin largely determines skin and fur colors. The more of this substance, the darker the skin, hair, or eyes of an individual. Melanin is stored in melanosomes — specialized structures within pigment cells.

In addition to the amount of melanin, the shape of melanosomes determines the cell’s color. Shorter, more oval-shaped melanosomes give a red tint, while longer ones of varying shapes produce black or shades of blue-green-yellow. This works in modern animals the same way it did for dinosaur-era ones.

By studying fossilized melanosomes, scientists can reconstruct the likely colors they produced. It’s a technique developed using living animals, by comparing their actual color against the shape of the melanosomes. Researchers used melanosomes to predict feather pigment and found the technique was 82% accurate.

This is how we know that the Microraptor, a small dinosaur, had glossy, raven-black feathers or that Sinosauropteryx sported reddish-striped tails. However, no researcher has tried the technique on prehistoric mammals. Until now.

Recreation of Microraptors based on melanosome analysis. Photo: Jason Brougham/University of Texas

New database needed

Existing databases of melanosome color came from research on birds. To understand mammalian color, researchers at the University of Ghent needed a new database. They used samples from 116 species, including monkeys, echidnas, cats, and sun bears. For the cat hairs, they used a sample from lead researcher Matthew Shawkey’s own pet, Masha.

Once they had a database of living mammals, they compared it with six extinct mammals. These ancient fossils all came from northeastern China but were millions of years apart and not closely related species.

The star of the show was a previously undescribed species of Euharamiyida. This was a family of early mammals that lived in trees and resembled the modern-day flying squirrel. This single fossil from the Hebei province of China was 158 million years old.

Thanks to melanosome analysis, researchers discovered that the animal had dark grey-brown fur all over. Because of this, they named it Arboroharamiya fuscus. In Latin, fuscus translates as “dusty,” or “dark-colored.”

A. Fuscus was small, weighing only 156 grams, about as much as a peach. It also likely had membranes between its arms and legs for gliding from branch to branch.

A. Fuscus’ color matched the other five species tested. They all had the same dark, grey-brown fur. They also probably lacked stripes or other markings.

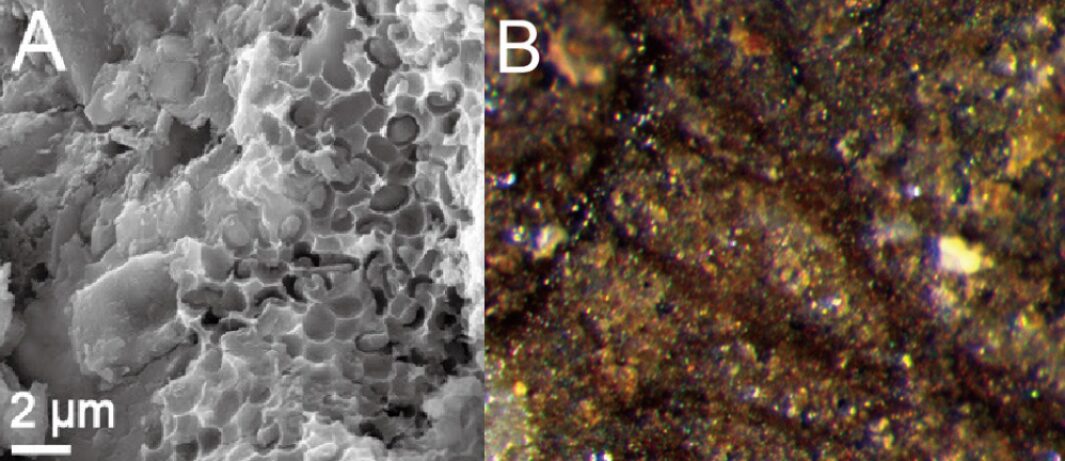

Fossilization preserved the microscopic structures that create pigment. Right, fossilized feather impressions. Left, microscopic image of the melanosomes.

Nocturnal lifestyle

These findings back up what researchers have long believed about early mammals: they were mostly nocturnal. During the day, they hid from the giant toothy dinosaurs, which would eat them if they were given the chance. At night, they crept from their holes to find food.

Our ancient rodent-like ancestors were a practical bunch. Their dark, bland coloring helped them blend into the nighttime environment.

Shawkey believes that fur color didn’t diversify much until about 66 million years ago. After the fall of the dinosaurs, early mammals took over the surface, becoming bigger and gaining brighter and more colorful coats.