British sailor Ella Hibbert is sailing alone around the entire Arctic Circle. If successful, she’ll be the first person ever to complete the 16,000km route solo and in a single season.

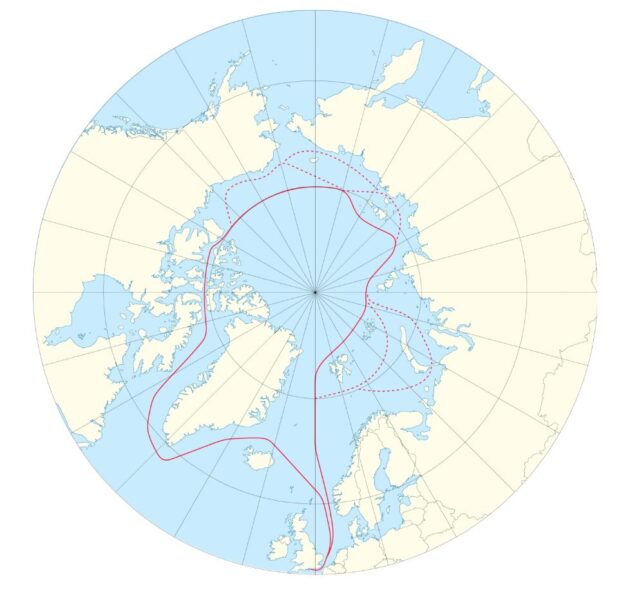

Last week, the 28-year-old set off from southern England and has since made her way up the east coast. Her official start point is the Arctic Circle (66.5°N latitude) between Norway and Iceland. From here, she will sail around Iceland, southern Greenland, through the Northwest Passage, then across northern Alaska, and into Russian waters. She will then cross the Northeast Passage and eventually return to her starting point before heading back to the UK.

The route. Image: Ella Hibbert

“It all started with my fascination with the Arctic,” she told ExplorersWeb. “I’d read about the Erebus and the Terror, that doomed early expedition. Then, as I got deeper into sailing, I started seriously thinking — could I go through the Northwest Passage myself? That idea evolved into this: a full circumnavigation of the Arctic, solo, to raise awareness of [the disappearing sea ice].”

A sailing instructor by trade, Hibbert has been organizing the project since 2022. “When I first said out loud that I was going to do this, I had no boat, no funding, and no idea how. But saying it made it real.”

First, find a boat

Her first priority was finding the right vessel. She had four must-haves: a boat under 12 meters (for easier solo handling), a steel hull (for safety in icy waters), a ketch rig (for sail versatility), and a doghouse to shelter from Arctic weather. After over a year of searching, she found Yeva, an 11.5-meter Bruce Roberts ketch built in 1978. There was only one problem — the boat wasn’t for sale.

Photo: Ella Hibbert

“I had to convince the old owner to part ways with her,” she said. “I didn’t have the money that he wanted for her, so I ran a crowdfunding page that raised a 20% deposit on the cost of the boat he was asking for. That was enough to convince him to let me pay off the rest month by month.”

Once Yeva was hers, the refit began: new engine, rigging, sails, electronics, and more.

“There’s not much on Yeva that hasn’t been replaced or serviced,” Hibbert said.

The sails are made from recycled plastic bottles, and she’s equipped with solar, wind, and water power generators.

“We’ve put all sorts of equipment on her, but my favorites are the hydrovane for self-steering without having to use electricity, which means less fuel consumption. And the water generator, which is an incredible bit of kit. If I’m sailing over four knots, it generates enough electricity to power the entire boat.”

Alongside the boat work, Hibbert has been preparing herself for total self-reliance.

Medical training

“I’ve done quite a lot of medical training, so I can put a cannula in my own veins for IV drips and morphine. I can do my own stitches and sutures. I’ve made sure that I know how to fix everything there is on the boat, so mechanics, electrics, and engineering. It’s been a lengthy process, but we finally made it.”

Photo: Ella Hibbert

She already has some solo experience, including a three-and-a-half-month training voyage in 2024.

“[I] sailed her over to Southern Norway, then did Southern Norway all the way up to Longyearbyen, and back down to Shetland and Scotland by myself. I absolutely loved it and managed to learn the aspects of single-handed sailing that I was unfamiliar with before.”

In the Arctic summer, she’ll have constant daylight. That helps with ice navigation but makes sleeping trickier. She thinks sleep deprivation may well be her biggest challenge.

Sleep deprivation

“It will be almost 24/7 daylight. If there’s any ice nearby, any ice within sight of the vessel, I won’t be sleeping. Even when the boat is moving, I will aim to sleep in 20-minute naps, get up, check everything…Obviously, that’s not sustainable for six months, so there will be times when I anchor for longer rests. Certainly, when the current is against me in places like the Northwest Passage, where the currents are too strong for me to try and sail into anyway.

“If I’m in an area of open water that’s ice-free, then I could do a tactic called heaving to, which is where you cross the sails over so that she can actually move forward through the water and she just drifts on the current and I could get a longer rest that way as well.”

” caption=”false”]

Russian Arctic

Sailing through the Russian Arctic is rare for a solo sailor, and getting permission was a bureaucratic nightmare.

“The main challenge was finding out who the right person to talk to was. It took about a year and a half to get those permits together, mainly because of the sanctions, not being able to look up online or email the right people. But once we managed to get a hold of them, they have been really lovely, supportive, and helpful. They’ve actually given me an extra two weeks’ allowance in my time frame to do that compared to what I originally asked for.”

She’s aware she likely won’t see another foreign yacht in Russian waters.

“There will be Russian icebreakers, and inevitably, fishing and shipping traffic. So not many boats of my size, but there are help and resources there if needed. Although obviously not as easily accessible as on the other side, in the Northwest Passage.”

The Northeast and Northwest Passages are notoriously tricky passages of water, and Hibbert is not sure which will be harder.

“It depends on where the ice is and on the weather. There are fewer fault holes and islands along the Northeast Passage for shelter. But there is slightly more open sea room, so it might be slightly easier to navigate than the Northwest Passage.”

All about the ice

The ice will play a key role in whether the expedition is successful. Hibbert will continuously assess the route and whether it is possible to complete it this season.

“There is a possibility of the ice being blown toward the Russian coastline for long enough that I don’t make it through the Northeast Passage. I won’t push into Russia unless I’m happy I can get out the other end, because it’s the last place that I want to get stuck for a winter alone in the ice or even in port. So, Nome, Alaska, is the halfway point of deciding whether we keep going. It will be up to the people sponsoring and funding the expedition as to whether we try again or pause and restart next year.”

Despite the huge number of challenges she knows she will face, Hibbert is full of excitement. “I can’t wait to see my first iceberg. Hopefully narwhals. Maybe even a polar bear — from a safe distance.”