Two legendary Americans deviating from the normal route, two Japanese topping out after ascending the entire direct line, two Swiss machines operating in pure alpine style, a dedicated British-Canadian, one Swede, and a few others who made bold attempts.

All these climbers are connected to the same line: the dangerous and exposed Everest Super Direct on the North Face of Everest.

In 1963, Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld ignored the normal Southeast Ridge-South Col route taken by their teammates. Instead, they ascended Everest by a new route up the West Ridge from the Western Cwm.

Traversing over the North Face to the dangerous couloir below the summit of Everest, since known as Hornbein Couloir, their ascent was one of the most impressive achievements in mountaineering history.

Willi Unsoeld (left) and Tom Hornbein on Everest. Photo: Tom Hornbein

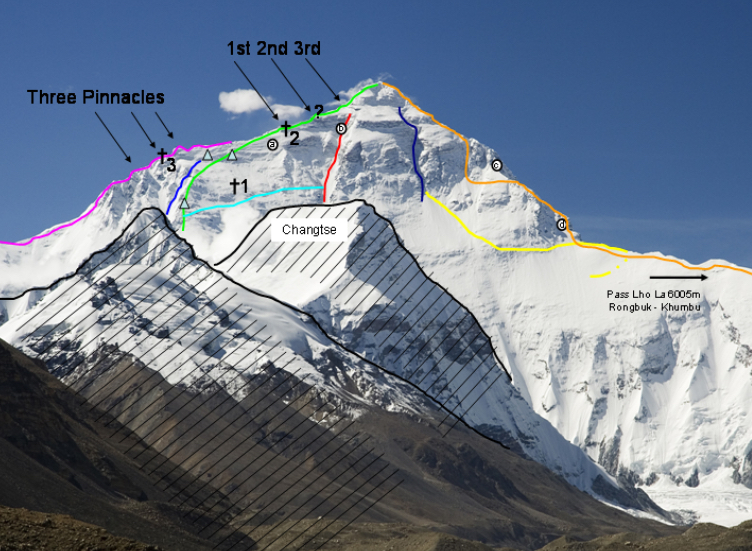

The Hornbein Couloir

The Hornbein Couloir is located west of the summit between 8,000m to 8,500m and is the origin of the Super Direct line. The narrow, steep couloir can be reached after climbing the West Ridge, or from the base of the North Face. The Hornbein Couloir is one of the most difficult sections on any 8,000m peak. Fewer than a dozen alpinists have climbed it, and it has claimed the lives of many others throughout the history of the mountain.

The dark blue line marks the Hornbein Couloir. Photo: Luca Galuzzi/Wikipedia

Japanese expedition to Everest North Side

In 1980, a large Japanese team from the Japanese Alpine Club attempted the North Side with bottled oxygen. The 19 climbers were divided into two parties. One would attempt the Northeast Ridge and the other the North Face from the bottom of a couloir that directly connects to the higher Hornbein Couloir.

Yasuo Kato, one of the 12-member Northeast Ridge party, summited successfully and then had to bivouac at the Second Step without oxygen. In the end, he managed to escape frostbite and descended safely.

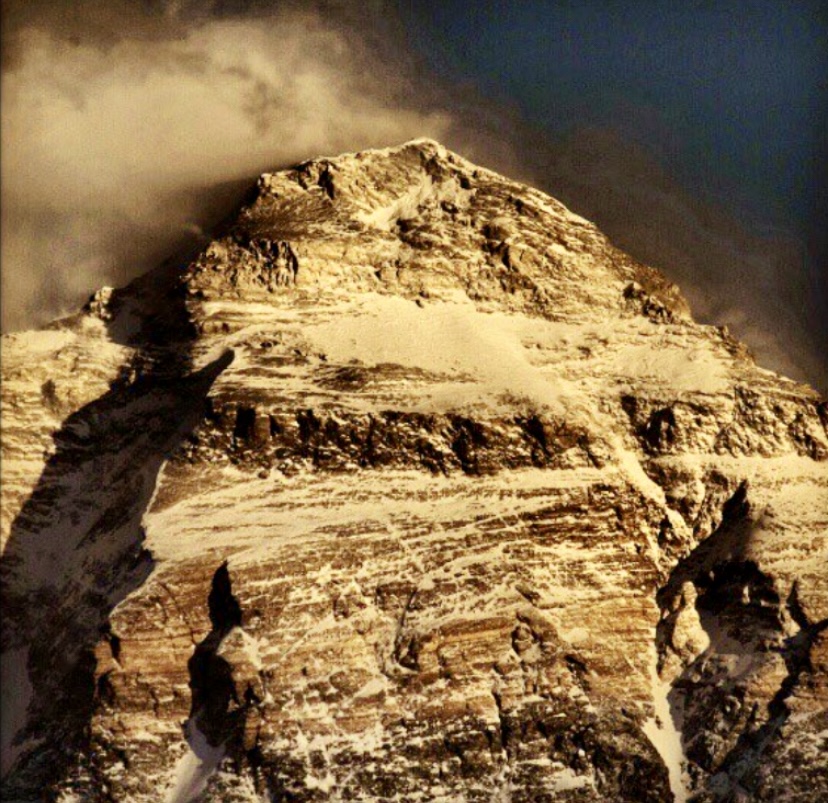

Hornbein Couloir. Photo: Jake Norton

Avalanche and fatality

According to Sadao Tambe’s report in the American Alpine Journal, the North Face party included 12 climbers led by Hideki Miyashita.

The North Face team placed its Camp 1 on the Central Rongbuk Glacier at 5,640m on March 9 and an advanced base camp at the head of the glacier at 6,150m on March 24.

The climbers found pitches of up to 60 degrees on the lower face. Nevertheless, they managed to make Camp 3 at 6,905m on April 4 and Camp 4 at 7,700m on April 18. Then they continued up the Hornbein Couloir, placing Camp 5 at 8,230m on April 25.

The team fixed rope up the entire face to 8,450m. The first summit team comprised Tsuneo Shigehiro, Takashi Ozaki, and Shohei Wada. Due to heavy snow, they had to give up at 8,580m.

On the same day, Toshiaki Kobayashi and Akira Ube were moving up to replace that first small team at Camp 5 when an avalanche hit them near the bottom of the Hornbein Couloir.

Ube was swept away. They found his body at the bottom of the face the next day.

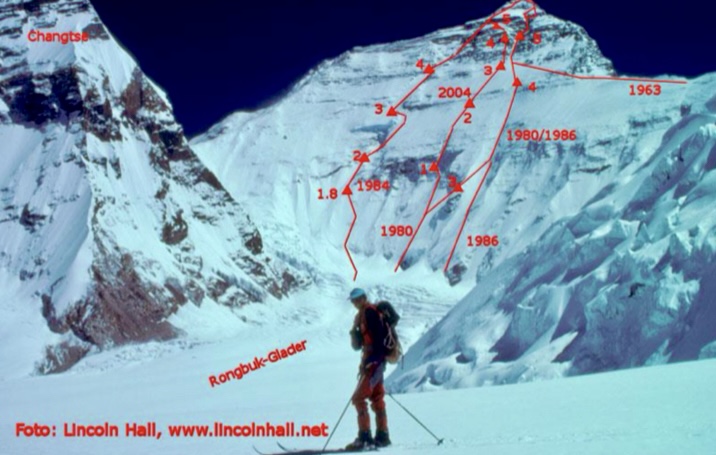

The Japanese route in 1980. Photo: Animal de Ruta

The first ascent of Everest Super Direct

But the others did not give up. They wanted a second chance to complete the direct line up the Hornbein Couloir to the summit.

On May 10, 1980, Ozaki and Shigehiro left Camp 5 on a new summit push. This was even more difficult than expected due to the large amount of fresh snow that had fallen the day before. Plus, both climbers ran out of oxygen four hours shy of the summit.

Despite this, the two climbers topped out successfully. They had to bivouac an hour below the summit during the descent before reaching Camp 5 the next morning. The following day, both went the rest of the way down without injuries.

The first part of the route, the couloir that the Japanese opened below the start of the Hornbein Couloir, was later dubbed the Japanese Couloir. Thus, the Everest Super Direct was born — a line that ascends both the Japanese and the Hornbein Couloirs.

Takashi Ozaki climbed Everest again in December 1983, and he died on Everest’s South Side in 2011 after having health problems and aborting the ascent at 8,600m. Photo: Kyodo News

1986 Loretan and Troillet, the ‘ne plus ultra’ ascent

In the summer of 1986, Swiss climbers Erhard Loretan and Jean Troillet made one of history’s most impressive mountaineering achievements — a fast and light alpine-style ascent of Everest Super Direct. Their route was a slightly different, parallel line from the one taken by the Japanese in 1980.

The original plan was that Jean Troillet would make a solo ascent of the Hornbein Couloir while Erhard Loretan and Pierre Beghin of France would climb the entire direct route. But according to The Himalayan Database, heavy snowfall in August caused all three to climb the Super Direct together.

Erhard Loretan (left) and Jean Troillet in 1994 during a later descent from Lhotse. Photo: Coll. Jean Troillet/Swiss Alpine Museum

Beyond limits

No sherpas, no supplementary oxygen, no ropes, no tent, no sleeping bags on the summit push, no backpacks above 8,000m. It was later called the “night naked” style because they climbed at night to avoid avalanches. According to the climbers, the Hornbein Couloir wasn’t too difficult, but the lower part of the face was very dangerous, with multiple avalanches tumbling down.

Beghin made two attempts but felt tired and finally bailed at 8,300m. For Loretan and Troillet, it was an almost nonstop ascent, carried out successfully over a period of 39 hours. They then glissaded down the mountain. From Base Camp to the summit of Everest and back to Base Camp took them only an astounding 41 hours.

Hornbein Couloir at sunset. Photo: Ed Webster

Lars Cronlund’s difficult 1991 descent

In 1991, Lars Cronlund, a member of a 21-member Swedish expedition supported by sherpas and bottled oxygen, made a summit push through the Japanese and Hornbein Couloirs. There had been two earlier summit attempts on this expedition, but Cronlund’s was successful. He topped out relatively late at 3 pm on May 15. The late hour led to problems during the ascent.

He hurried to descend to avoid the darkness that began around 7 pm, but he could not find the fixed ropes at the top of the couloir. He wandered most of the night, searching in vain. Exhausted, he accidentally fell asleep. At 7 am the next morning, he awoke to discover frostbitten toes and increasing winds.

It was a struggle for Cronlund to reach Camp 5, but he finally descended with the help of a partner who met him at 8,500m.

The 1980 Japanese and 1986 Swiss routes on the North Face of Everest. Loretan and partners climbed along the rib to the right of the 1980 Japanese Couloir. They would reach the Japanese route at an altitude of 7,000m in the Couloir itself. Photo: Lincoln Hall/Gunther Seyfferth

Bold attempts

In the spring of 1987, Roger Marshall wanted to ascend the Super Direct in pure style — and solo to boot. He was critical of ascents supported by sherpas and bottled oxygen. Like Loretan and Troillet, Marshall planned to climb at night and rest during the day.

However, in the spring of 1987, there wasn’t as much snow as in August 1986. The difficulty of climbing without snow, on only rock and blue ice, made him change his plans and climb in daylight.

At 7,850m, Marshall started to suffer altitude sickness and decided to abort the summit push and turn around. A determined but impatient climber, Marshall fell 150-300m down the North Face on May 21 and died.

Ralf Dujmovits climbs the first pitch above the bergschrund at about 6,800m on the Japanese Couloir in 2010. Photo: Ralf Dujmovits

Different teams and countries made valiant attempts along the route in 1988, 1989, 1995, 2003, and 2006. None reached the top, although some reached 8,500m.

In 2010, Ralf Dujmovits and Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner wanted to ascend the line without O2 or sherpa support. Kaltenbrunner finally summited by the North Col-Northeast Ridge.

Loretan’s conclusion after his successful 1986 ascent? “This very light alpine style makes it possible to do more difficult routes and longer traverses on 8,000’ers.”

Erhard Loretan on Aug. 30, 1986, on the summit of Everest. Photo: Coll. Jean Troillet/Swiss Alpine Museum