Interested in exploration reading but don’t know where to start? Or perhaps you have a library card burning a hole in your pocket? For those looking to dive into the history of discovery, we’ve assembled the following introduction, ordered by chronological eras.

Of course, this is just the tip of the iceberg; beware, for you soon may find yourself hankering for exploration literature that can only be acquired by getting your Swiss friend to scan something from the University of Geneva’s special collections (theoretically).

‘Man proposes, God disposes,’ painted in 1864 by Edwin Landseer, is perhaps the most iconic painting in the history of exploration. Referencing the failure of the doomed Franklin Expedition, it captures the tension between hubristic human effort and the terrible fate many explorers ultimately met. Photo: Royal Holloway, University of London

The mythological dawn of exploration

The earliest exploration literature is indistinguishable from mythology. The Hellenistic explorer Megasthenes wrote Indica, about his travels to India around 300 BCE. It’s now a lost work, surviving only in fragments, just like his peer Pytheas‘s account of exploring Northern Europe.

In this period, Greeks and then Romans were expanding into Gaul and Britannia, now encompassing Western Europe and the British Isles. They were also spreading into North Africa and India. To the east, Chinese explorers like the monk Faxian were also traveling to India and Central Asia.

Polynesian explorers undertook vast voyages across the Pacific, settling on islands separated by thousands of watery kilometers. Oral tradition records the legendary Ui-te-Rangiora, who reached a bitterly cold region that some believe may have been Antarctica.

For this genre of mytho-historical exploration writing, try the Alexander Romance. In late classical and early medieval writing, Alexander the Great’s military exploits often took a back seat to his role as an explorer of India and Persia. The Alexander Romance, though partly compiled from the accounts of those who knew him, is a fantastical work composed in Ancient Greek. It’s been translated over a hundred times and fueled a thousand years of Western imaginings about India and the East.

A naval officer in Alexander the Great’s army, Nearchus completed a celebrated journey from the Indus River to the mouth of the Tigris. Like so many other ancient accounts, his story of the voyage is now lost. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Explorer-monks of early medieval literature

The stories of medieval exploration, especially in the early medieval era, were still interwoven with fictional, allegorical, and religious elements. While the journeys themselves may be more verifiable, their details are often just as fantastic as those of classical explorations. Many key exploration narratives were only written several hundred years after the fact, further obscuring reality.

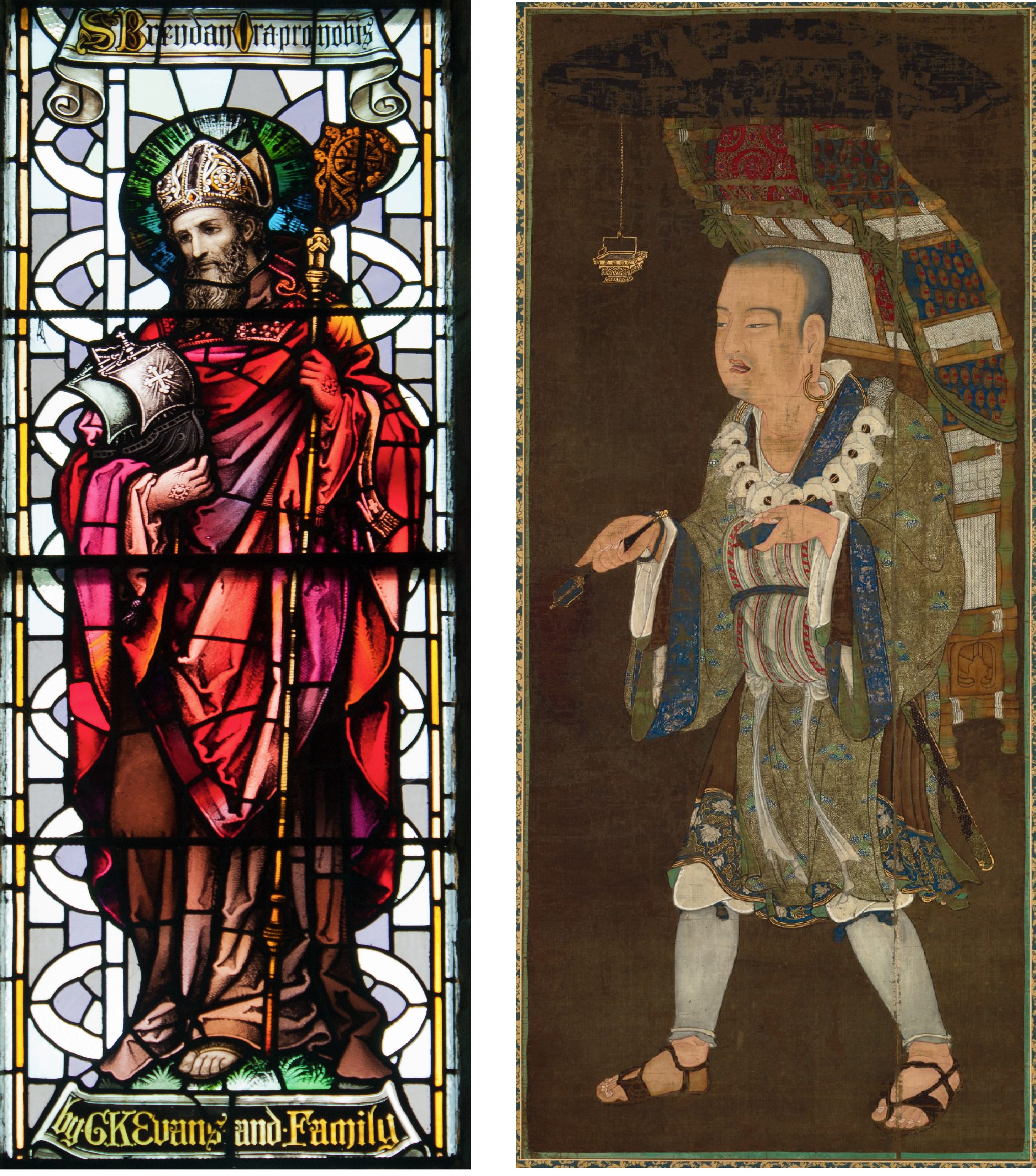

One early medieval voyager who exemplifies the blend between history, myth, and religious allegory is Saint Brendan the Navigator, who undertook a legendary sea journey in search of a blessed island. His 6th-century voyage is recorded in the 10th-century work, Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (Voyage of Saint Brendan).

Meanwhile, in China, exploration of India continued. By far the most famous of these early medieval Chinese explorers is Xuanzang, a Buddhist monk from the early 7th century. Xuanzang undertook a 17-year journey to India to bring back and translate important Sanskrit texts.

You can read his account, Records of the Western Regions, detailing his 16,000km journey down the Silk Road. Or, you can read the famous 16th-century Chinese novel, Journey to the West. It’s a much less useful historical source, but has far more demon fights.

St. Brendan, left, from a church in Glenbeigh, Ireland, and Xuanzang from a 14th-century painting. Photo: Wikimedia/Smithsonian Institution

Viking intermission

When they weren’t busy pillaging Irish monasteries and blood feuding with each other, the Scandinavian voyagers of the High Middle Ages were exploring the edges of their known world. A pair of Norse sagas record how Vikings, led by Eric the Red and then his son, Leif Eriksson, crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

The explorers of the Grænlendinga saga, or Saga of the Greenlanders, and Eiríks saga rauða, or Erik the Red’s Saga, were the first Europeans confirmed to reach North America. There, they established a settlement named Vinland. But battle with the indigenous inhabitants, family drama, and the logistical challenges of maintaining a colony so far from home eventually led them to abandon Vinland.

A replica Viking longboat. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Exploring during the High Middle Ages

Meanwhile, back on the Eurasian continent, in Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree — and an Italian was there to write it down. His name was Marco Polo, known to schoolchildren as the inventor of a popular swimming pool game.

Of course, Marco Polo did not invent that game; he was actually a Venetian who traveled through Asia along the Silk Road in the late 13th century. Eventually, he came to reside in the court of Kublai Khan, Mongol emperor, ruler of China, and grandson of Genghis Khan. Polo wrote his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, from a Genovese prison. His account gives an outsider’s perspective on daily life in Asia and what it was like to travel the Silk Road at the height of its importance.

In 1324, a young Amazigh man named Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battuta left his home in Tangier to go on Hajj — the once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage required of every Muslim. The journey to Mecca and back should have taken about 18 months. Instead, Ibn Battuta returned after 24 years of travel through Africa, Asia, and Iberia, covering over 117,000km. Finally back in Tangier, Ibn Battuta wrote his travel memoir, The Rihla.

A colorful illustration from a medieval edition of Polo’s book, which was as close to a bestseller as something could be before the printing press. Photo: Shutterstock

The Age of Exploration

Around the 15th century, Europe started getting serious about exploring. The causes are complex: new technology, changing political and economic structures, power shifts in the Middle East cutting off trade routes — you could fill a book, and many have. But the upshot was that over the next few centuries, a lot of men got into rickety wooden boats and pointed them at the horizon.

Mediterranean powers, including Portugal, Spain, and various Italian city-states, set their sights on new routes to the Indies. Some of these expeditions ended up in the Americas, where they bravely made the best of things by pillaging America instead of Southeast Asia.

The seminal man of the era was Christopher Columbus, who treated the indigenous people he met so badly that Ferdinand and Isabella, the Spanish monarchs who were implementing the Spanish Inquisition and expelling the Jewish population from Spain, had him dragged back in chains.

But the most crucial introductory account of Spanish exploration and conquest in the New World is A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, by Dominican friar Bartolome de las Casas. De las Cases spent four decades in Spain’s colonies and dedicated his life to campaigning against the horrors being wrought there. The resulting writings are as fascinating as they are grim.

De las Casas wrote his volumes to present to European monarchs, begging them to intervene on behalf of the indigenous people of the New World. Photo: Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City

The search for trade routes

The discovery of vast new lands didn’t mean European markets forgot about the wealth of spices and luxury goods in Southeast Asia. Portugal had attained early dominance of the spice trade by pioneering a new route around the bottom of Africa, via the Cape of Good Hope.

Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese navigator in the employ of Spain, tried another route, heading the other way, around the bottom of South America. In 1519, Magellan set sail with five ships and nearly 300 men. In 1522, 18 of those men, in the one remaining seaworthy ship, returned to Spain, becoming the first people to circumnavigate the globe. Magellan died on the way.

The First Voyage Round the World is an account by one of the survivors, the Venetian . They faced storms, starvation, and scurvy, undertook the first navigation of the Strait of Magellan, and battled their shipmates in a brutally repressed mutiny.

England, meanwhile, had begun a long-standing obsession with sending people to die in the Arctic looking for the Northwest and Northeast passages. The Dutch, also trying to dominate the spice trade, tried to pioneer a northern route as well. Eventually, they gave up and went back to using the route around Africa, but England stuck with it. More on that later.

Magellan died in the Philippines at the Battle of Mactan. Magellan had landed on the island and demanded that everyone convert to Christianity and give him all the food he needed to resupply his ships. When Magellan tried to put down a rebellion led by Chief Datu Lapulapu by burning down native houses, Lapulapu’s troops rushed the beach and slew Magellan. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

An account of the voyages

As the Enlightenment and the rise of mercantilism and the nation-state affected social, political, and economic thought, the motivation for exploration changed. Wealth and power were still huge factors, but the twin desires of scientific discovery and patriotic fervor joined them. Expeditions were still sponsored by companies and governments, but as we entered the 19th century, organizations like the Royal Geographical Society and French Société de Géographie grew in prominence.

James Cook, who explored the Pacific and Southern oceans in the late 18th century, was a model for later explorers. A British Royal Navy captain who turned to discovery, the goal of his first voyage was to confirm rumors of Australia and claim it for the British crown. He landed in Botany Bay and, while Cook was firing cannons at the Aboriginal Gweagal people, botanist Joseph Banks did some botany.

Cook went on two further voyages to the region, accomplishing feats of discovery and antagonizing the locals. He finally died on Valentine’s Day, 1779, when he tried to kidnap the Hawaiian king, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, and was clubbed to death.

In 1773, John Hawkesworth published An Account of the Voyages (title here abbreviated considerably). This work includes Banks’ and Cook’s personal accounts of their voyage together, as well as journals from two other contemporary voyages in the South Pacific.

This work by Johann Zoffany, who knew Cook, conflicts with eyewitness accounts of his death, which have him taking a more active role in the fighting. Photo: Greenwich Maritime Museum

The race to record the world

Now that everyone knew how many continents there were, the goal became more exact maps, more efficient routes, better navigation methods, and to claim more “firsts” for one’s country. Areas deemed “unexplored” were shrinking, as explorers focused more on the polar regions, as well as the vast interiors of Africa, the Americas, and Australia.

As well as claiming land, there was now another way for an explorer to advertise success: scientific specimens. The great scientific societies of Europe wanted specimens of new species, and owners of the great gardens of Europe hankered for exotic plants.

By far the most famous of the naturalist-explorers is Charles Darwin. Better known for a later book, Darwin wrote The Voyage of the Beagle about his time as a naturalist on a five-year voyage around the world.

This full-size replica of HMS Beagle resides in Chile’s Nao Victoria Museum. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Any progress on the Northwest Passage?

The Royal Navy still had its eyes on the Poles. They sent dozens of expeditions to the Arctic after those fabled passages, and several more to the Antarctic. It was in the Antarctic that HMS Erebus and HMS Terror cut their teeth under Sir James Clark Ross, and the eternal second-in-command, Francis Crozier.

In 1845, Erebus and Terror went to the Arctic under Sir John Franklin. It didn’t go well.

Helen of Troy’s face launched a thousand ships, and Franklin’s missing one launched a thousand more. One of the searchers was by Elisha Kane Kent, who wrote Arctic Explorations: the Second Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin about his arduous, failed effort.

Success went to John Rae, who discovered what happened to Franklin by asking the people who had been there (the local Inuit), something no one else had tried before. He brought back the true story and promptly had his name dragged through the mud by Charles Dickens. No good deed goes unpunished.

The whole affair temporarily cooled polar exploration fever, and the bulk of interest and funding turned to Africa and the Amazon.

The artist exhibited this painting, titled ‘They forged the last links with their lives’, for the 50th anniversary of the Franklin Expedition. Photo: Greenwich Maritime Museum

The Heroic Age

The so-called Heroic Age began with a renaissance of interest in polar exploration. The “heroic” title comes from the perception that these explorers were overcoming great adversity, testing their physical and mental endurance.

While many explorers framed their expeditions as being for the sake of science, pride, fame, and fortune were often the true reasons. You didn’t get funding to look at plankton in the Antarctic Ocean; you got funding to plant your country’s flag at the Pole.

Here we come to the heavy hitters of exploration literature: memoirs from the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration. There are hundreds of them, and many are quite good, but I’ve narrowed it down to a few.

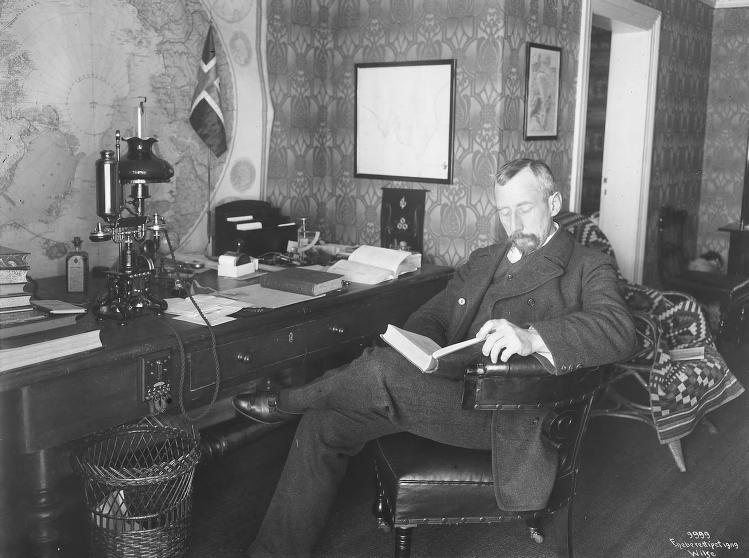

Fridtjof Nansen is best described as your favorite polar explorer’s favorite polar explorer. As well as being a neuroscientist, polymath, and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Nansen helped kick off the Heroic Age with his 1888 traverse of Greenland and the even more influential 1893–1896 Fram expedition. Chronicled in his book Farthest North, the expedition was a daring, years-long effort that took him and companion Hjalmar Johansen to 86°13.6′ N, setting what was then the record for farthest north.

Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s The Voyage of the Discovery is another quintessential work. It’s his account of his 1901 Antarctic voyage with several other men soon to etch their names into the annals of Polar history: Edward Wilson, Frank Wild, Tom Crean, and Ernest Shackleton.

Nansen intentionally froze his ship, the Fram, in the ice, then allowed the current to take it north. Nobody thought it would work, but it did, a fact he extensively points out in his book. Photo: Fram Museum

Polar hardship literature

Roald Amundsen claimed the South Pole in 1911, while the North Pole was first reached by Frederick Cook. Scratch that, it was Robert Peary, Richard Byrd, it was Roald Amundsen again. It was briefly popular to claim you reached the pole, then fail to provide evidence. Roald also got the Northwest Passage, hat trick!

While Amundsen’s books are interesting, I must reluctantly admit that they are not topping any lists focused on literary value. There’s not as much drama when good planning, skill, and luck result in everything going pretty smoothly. The best books of the Heroic Age are from expeditions that did not succeed.

South by Shackleton is one of those classic tales of an indomitable human spirit. Shackleton tells a mostly honest, if tonally positive, account of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, which abruptly became a struggle for survival when their ship, Endurance, became trapped in the ice and sank. The most astonishing part of the story is that, unlike nearly every other similar tale, the crew all lived.

If you read any of the books mentioned in this article, let it be Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s The Worst Journey in the World. Cherry published the book, a memoir of his experience in Robert Falcon Scott’s ill-fated Antarctic expedition, a decade after the actual events. Cherry’s account of the expedition is funny and tragic in turns, but always deeply personal. Some literary types, including travel writer Paul Theroux, consider The Worst Journey the best travel book ever written. The 70-page account of their winter journey in quest of emperor penguins’ eggs is truly magnificent, but then there are another 500 less interesting pages on the Scott expedition to wade through before you come to the last two or three pages of the book, which manage to attain the heights of great literature.

Henry ‘Birdie’ Bowers, Edward “Uncle Bill” Wilson, and Apsley Cherry-Garrard, about to set off on the winter journey to the penguin rookery, Cherry’s titular ‘worst journey.’ Bowers and Wilson both perished on the return journey from the South Pole. Photo: Herbert Ponting/Public domain

Modern explorers and adventurers

In an age of radar, satellites, and accurate maps, exploration, at least on Earth, has changed. Some seek new horizons among the stars or deep beneath the sea. Others turn to the past, using experimental archaeology to learn more about historic explorers.

Of these, perhaps none is more quintessential than the work of Tom Severin. A British explorer, author, and historian, Severin spent 40 years recreating and testing legendary voyages. His most famous brings us back to Saint Brendan the Navigator.

In 1976, Severin built a replica of Brendan’s currach, an ancient Irish hide-covered boat, and successfully sailed it over 7,000km from Ireland to Canada. He published an account of his journey in The Brendan Voyage, which became a bestseller.

Doubtless, the future of exploration lies beyond our planet. It’s a topic I don’t dare insult by cramming it in at the end. But while what I’ve left out dwarfs what I’ve managed to include, I hope the interested newcomer has at least found enough to get started.