It’s 1553, and Sir Hugh Willoughby is leading three ships into uncharted arctic waters to search for the Northeast Passage — a direct route from Europe to China and India via northern Russia.

His expedition set out from Ratcliffe, a shipbuilding center on the outskirts of London. Three proud ships make their way down the Thames, past crowds of onlookers along the riverside, as the captain stands tall on the prow of his flagship. He is never seen alive again.

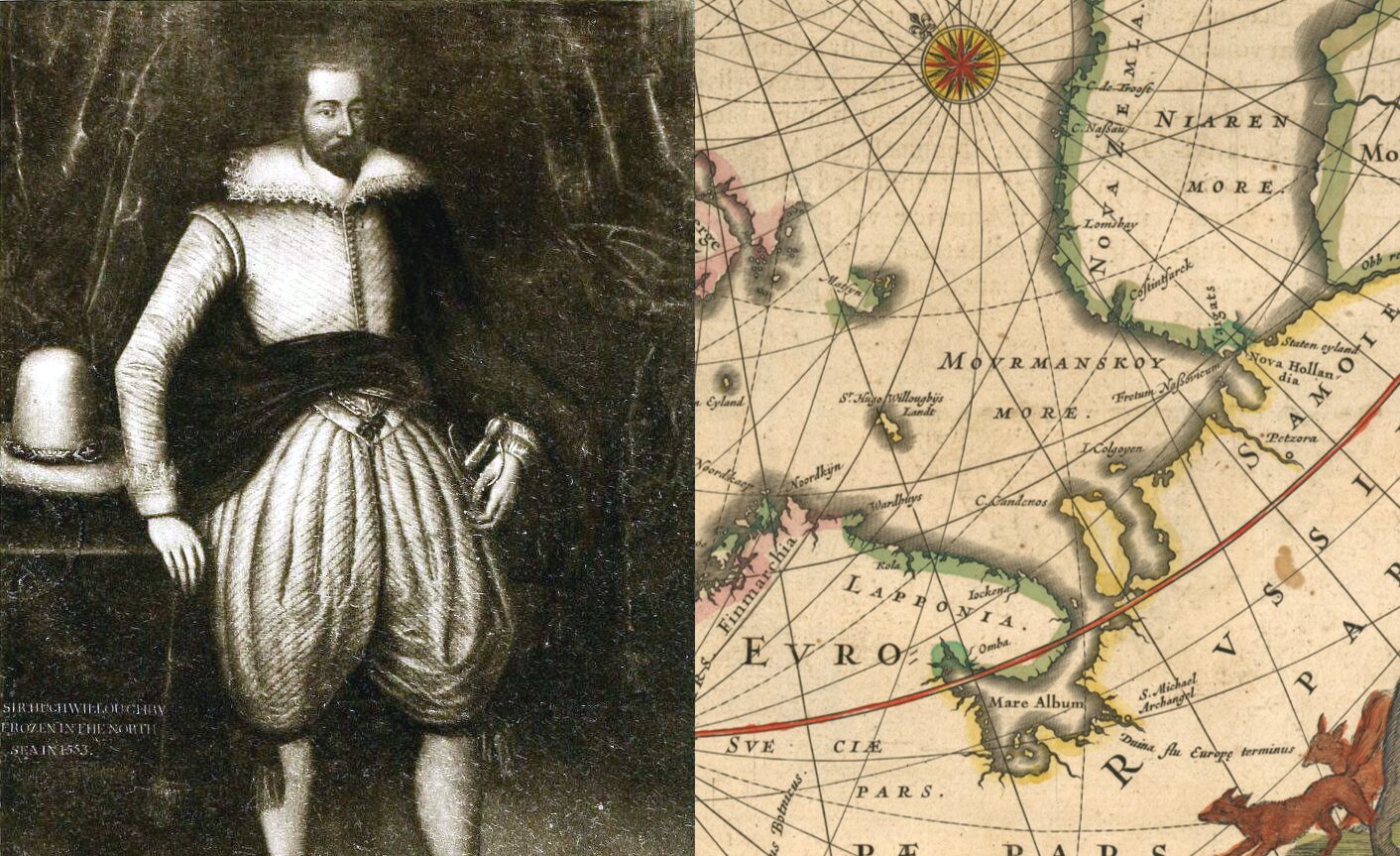

An engraving of ‘England’s Famous Discoverers,’ with Willoughby center right. Photo: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

An unlikely captain

Willoughby might have looked the part while the ships set sail, but he was a surprising choice to lead an arctic expedition. He had no seafaring or navigation experience and had likely never left the British Isles before. But he had a talent for impressing the right people at the right time.

By the time he was a teenager, Hugh’s wealthy noble parents had both died. As a younger son, he received just a small share of his father’s estate. His older brother John received instructions to look after Hugh and find him a wife.

Hugh did not find a wife (though he did acquire a daughter at some point). However, he took a lesson from his late father, who earned a knighthood from his military service during the Wars of the Roses. The lesson was this: In the tumultuous social and political world of Tudor England, advancement could come readily to young noblemen willing to get their swords dirty.

The house on the Middleton Estate which belonged to the Willoughby family. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Martial glory?

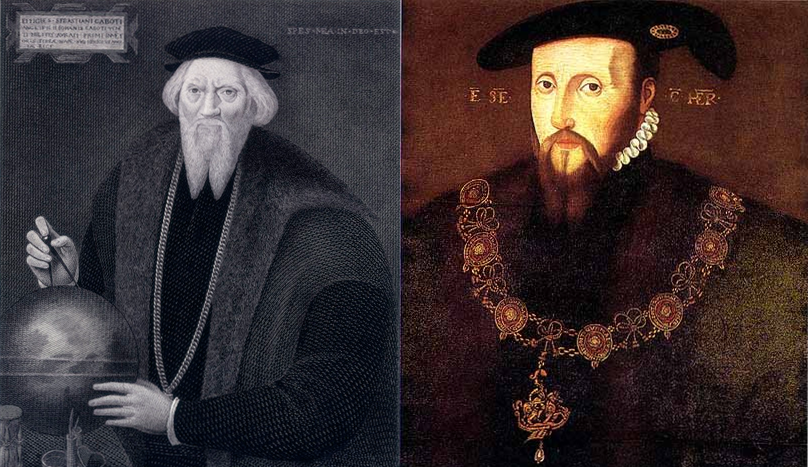

Hugh began his career fighting in the Scottish border wars. In 1544, he was knighted by his commander, Edward Seymour, the Earl of Hertford, and became Sir Hugh Willoughby.

His networking continued to pay off. In 1547, the king died, leaving his nine-year-old son Edward on the throne and appointing a council to rule until the boy came of age. Heading that council was Sir Hugh’s old friend Edward Seymour, now the Duke of Somerset and the most powerful man in England. Somerset made Hugh the captain of Lowther Castle so he could continue menacing the Scots.

By 1549, however, Somerset had become a controversial ally. Unpopular policy decisions and failed military campaigns led to his fall from power. Somerset himself spent a few years in and out of the Tower of London before losing his head.

Seeing all this going down, Sir Hugh decided it was time for a career change. Inspired by seafaring friends, including Venetian explorer Sebastian Cabot, he became a sea captain.

Two patrons of Willoughby. Left, Sebastian Cabot. Right, England’s Lord Protector, the Duke of Somerset.

Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands

Cabot was in England, serving as central authority in all maritime and shipping matters, when Hugh befriended him. Sir Hugh, Sebastian Cabot, and a third man, Richard Chancellor, formed a company in 1551. Like Cabot, Chancellor was a career explorer and seaman. All three shared the goal of finding a Northeast Passage to “Cathay” (China) and the spice riches it would bring.

It was called the Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands. In 1553, King Edward VI formally incorporated them. They wasted no time setting up their first expedition, which Sir Hugh Willoughby was to command.

Yes, he had no seafaring experience, but he was a proven military leader. He was also tall — his “goodly stature” was mentioned in contemporary accounts — so he at least looked the part of the explorer.

While Willoughby was in overall command, Richard Chancellor was the “pilot general” of the fleet, in charge of the day-to-day navigation and sailing.

Cannibals and swearing

The expedition had resources and funding that later explorers could only dream of. The company had three ships built specifically for the voyage under Hugh’s command. His flagship was the Bona Esperanza, with a crew of 34. The largest vessel was the Edward Bonaventure, captained by Richard Chancellor with 49 men. Finally, there was the Bona Confidentia, carrying 28 men.

The company supplied the ships with 18 months of food, and armor and munitions as well, just in case. These 16th-century vessels were comparatively small; the largest ship was only about half the size of Sir John Franklin’s flagship, HMS Erebus.

Sebastian Cabot put together lengthy instructions to Hugh in a 33-item-long letter that covered everything from the dressing and feeding of the men to the goals of the voyage. It also contained moral guidelines. For example, item 12 said not to allow “blaspheming of God, detestable swearing… filthy tales or ungodly talk,” and also banned any form of gambling.

Cabot alerted Hugh to possible dangers he might encounter. Item 30 warned that some people might wear bear or wolf skins but that Hugh shouldn’t let that alarm him; they only wore them to scare people. Item 31 cautioned him to keep a close watch against naked cannibals who swam in rivers, lakes, and seas and would steal onto the boats to eat the crew.

Well-warned against the dangers of cannibals and swearing, Hugh was ready to set sail. On May 10, the three ships began their journey down the Thames.

While attacks from swimming cannibals were unlikely, 16th-century Europeans imagined foreign people as frightening monsters. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Setting sail

The departure was not without hiccups. Two ill sailors had to be discharged before the voyage even began. Another was caught stealing. Sir Hugh had him ducked at the yardarm, an antique naval punishment wherein the offender would be tied to the end of the yard and dunked multiple times underwater, often while cannons were fired over his head. The thief was then discharged.

Staffing issues resolved, they continued their cheery river cruise, saluting a dying Edward VI as they passed Greenwich. The king had given Sir Hugh a long letter, translated into English, Latin, Greek, and various other languages, to give to any foreign monarchs he might meet on his travels.

Bad winds then delayed the voyage. For weeks, the weather forced them to anchor off East Anglia, waiting for a change. While there, they discovered the wine casks leaked and a significant amount of the provisions were bad. Willoughby decided that it was too late to go back and resupply, and they forged ahead as soon as the wind allowed.

The wine flasks probably looked like this one, which was recovered from the wreck of the ‘Mary Rose,’ another Tudor ship. Photo: The Mary Rose Trust

Ships in the night

It wasn’t until mid-July that they finally reached the coast of Norway. They spent several weeks at harbor in various small Norwegian islands, then under Danish rule. The people were friendly and hospitable, and the crews spent their time hunting “diverse fowl.”

They were about to enter the harbor of Finmark when the weather turned bad again. In danger of being forced against the rocky cliffs by the strong winds, the ships quickly fled to sea. They headed vaguely northeast, hoping only to escape foundering. Soon the storm grew so strong that all the sails had to be taken in, and all the men could do was wait for the weather to pass.

That is how they spent the night of July 30. Conditions were terrible. One of the small boats on the deck of the Bona Esperanza was flung so hard against the side of the ship that it shattered into pieces.

In the morning, from onboard the Bona Esperanza, Willoughby looked for his other two ships. Off to the leeward, they spotted the little Bona Confidentia, which had come through alright. But the Edward Bonaventure — Willoughby’s largest ship and the one which held his navigator and sailing master — was nowhere to be seen.

For several days, the two ships continued wearing out the storm and scanning the horizon for their missing third party. But they never saw the Edward Bonaventure or their 49 comrades again.

Overwintering

Willoughby sailed his two remaining ships on, heading northeast. On August 14, they sighted land but could not go ashore because of shoals. The Confidence had sprung a leak, and her bilge was filling with water. They needed a place to anchor. They kept moving, trying to stick near enough to the coast of Lapland to spot potential harbors.

On September 18, they found a “haven” at the mouth of the Arzina River. The harbor was about five kilometers by ten, and deep enough for their ships. Willoughby even judged, “by crosses and other signs,” that there was evidence of human activity in the area. The harbor also supported lots of wildlife. There were seals and fish in the water, and on the nearby shore, they sighted bears, deer, foxes, and other animals they did not have names for.

They stayed there as the weather worsened. If, Hugh wondered, conditions were this bad in September, how much colder and stormier would true winter be? Additionally, he had no experienced navigators with him, and they did not know where they were. At the end of a week in the harbor, Sir Hugh made the decision that they would winter there.

They immediately set about preparing to overwinter. Hugh sent out three scouting parties to look for people, but despite the signs Hugh had observed earlier, they found no one. Sir Hugh and his men would be wintering alone.

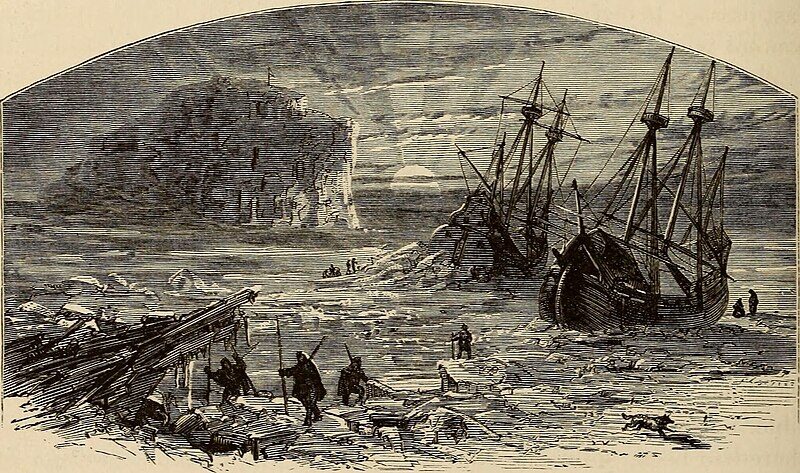

An engraving of ‘Hugh Willoughby’s Ships in Arctic Seas’. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Fate of the Edward Bonaventure

Meanwhile, the terrible storm off North Cape had not sunk the lost Edward Bonaventure. In fact, Richard Chancellor had successfully sailed on to the port of Vardø, their planned meeting point. After a week of waiting, he decided to continue on alone. He entered arctic waters and headed east.

While not quite discovering the Northeast Passage, Chancellor became the first explorer to enter the White Sea. They sailed on, making contact with and heeding the advice of local people. The ship landed in what is now the Russian port of Archangel, at the mouth of the Dvina River.

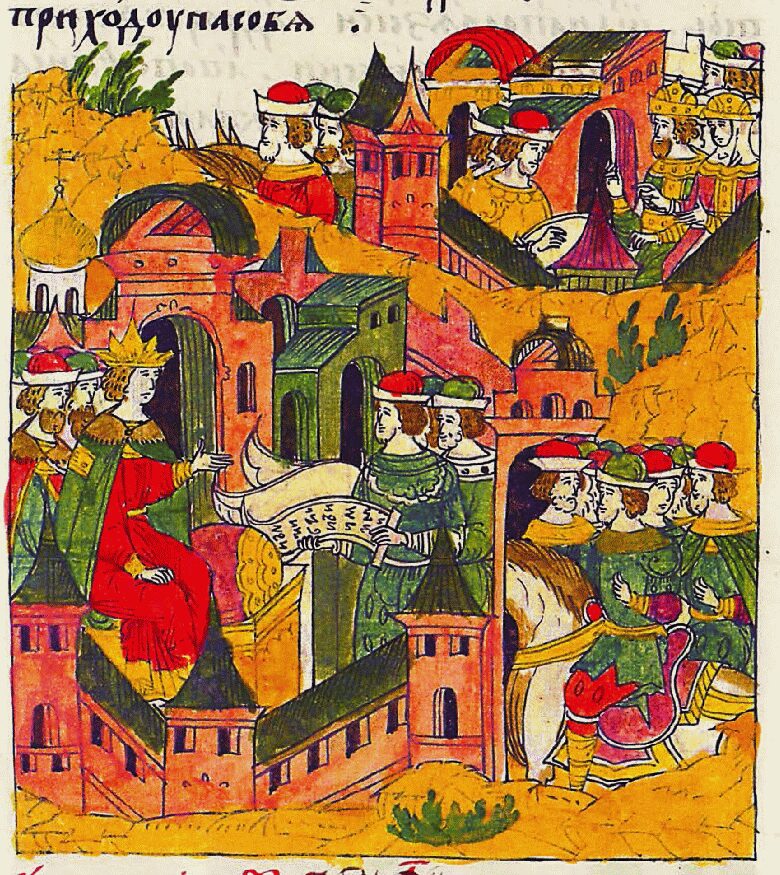

The letters they had been given for foreign potentates came in handy. Tsar Ivan, of “the Terrible” fame, heard about the English ship that had arrived on his shores and sent for Chancellor. Leaving his men to winter on the ship, Chancellor undertook a sleigh journey of over a thousand kilometers. He arrived in Moscow, where Ivan treated him to grand celebrations and feasting.

There, he negotiated a trade agreement with Russia. They would provide a market for English wool, and he could, in turn, bring back fur goods. The next spring, Chancellor returned to the Edward Bonaventure and sailed back to England without incident.

An illustration from a 16th-century illuminated Russian manuscript shows the visit of Richard Chancellor to Moscow. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What the fishermen saw

While his erstwhile second in command was being feted in Moscow, things had become grim for Willoughby and his men. Willoughby had stopped recording in his journal, focused on keeping his crew together over the long, hard winter. They decided not to build structures on the shore, but to stay on their ships.

By January of 1555, things had gotten bad enough for Sir Hugh to write out his will. At that point, all or most of the men were alive. After that, the record stops.

Russian fishermen, whose signs Willoughby had noted when he arrived, returned to the area when the weather began to warm. They were surprised when they found two strange ships in the harbor. They were likely even more surprised when they went on board and found that everyone was dead.

Meanwhile, eager to take advantage of the new trading partner that Chancellor had acquired, English merchants quickly prepared to sail into the frozen North. The first, led by George Killingworth, reached Moscow in the summer of 1555.

There, they heard that fishermen had found frozen ships full of dead Englishmen. Knowing this must be the missing Sir Hugh Willoughby, they made the 1,000-kilometer journey from Moscow to Lapland.

The ships and the dead men inside were still there. Descriptions of the scenes inside the ships were nightmarish. The men froze where they died. There were no graves on shore, so they must have perished quickly.

Killingworth repurposed many of the goods and supplies on board and recovered the bodies. The two ships were refitted in a Russian dockyard.

English merchants and ambassadors rushed to Moscow, hoping to gain riches and fame, as depicted in this 1875 painting by Alexander Litovchenko. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Scurvy, cold, or suffocation?

Early English arctic expeditions lacked knowledge and experience. Their clothes were inadequate, and the wooden ships kept out water but did not insulate against the cold. Heating them required massive amounts of fuel. In addition, the men likely suffered from scurvy. Though the plentiful game in the area could provide fresh meat, a source of vitamin C, much of the crew’s diet would have come from their stores aboard ship.

These two causes — scurvy and the cold — have been the usual explanations for the deaths of Willoughby and his men. But there are problems with these theories.

While the early symptoms of scurvy likely afflicted some of the crew, they weren’t away long enough to die in large numbers. Besides, the fact that there were no graves on shore meant that they had all died quickly, together — not from slow illness. The same applies to cold, which would have taken the weaker members first.

While no artifacts from Sir Hugh’s expedition survive, similar arctic expeditions in the following decade show the clothes worn. Wool stockings and shirts, felt and knitted caps would not have been warm enough. Photo: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

New theory

In 1986, scholar Eleanora C. Gordon proposed a new theory: carbon monoxide poisoning. Hoping to conserve heat and fuel, the 63 men gathered together below decks on one of the ships, tightly closing all the hatches against the freezing drafts. The coal they burned gave off carbon monoxide, which became highly concentrated in the small, unventilated space. The gas is invisible and odorless, silently replacing the oxygen in their blood.

If they felt dizzy, tired, and weak, it was easily attributable to the cold. By the time they lost consciousness, it was too late. They all died together, their safe haven becoming their tomb.

Sixteenth-century explorers lacked the skills and knowledge to survive in the Arctic. Shown here in a painting of the death of William Barents in 1597.

Lost, found, and lost again

Killingworth brought the story back to England, where Richard Chancellor finally learned the fate of the rest of his expedition. His upcoming return visit to Russia took on a new dimension. In addition to the new trade route, he would bring the rediscovered ships and an account of the disaster back home.

In July of 1556, after another visit to Moscow, Chancellor reunited the Bona Confidentia and Bona Esperanza with his own ship, the Edward Bonaventure. The voyage back was disastrous.

The Bona Confidentia was separated from the fleet and never seen again, and Bona Esperanza struck rocks off the coast of Norway and was lost with all hands. Then, on the 10th of November, the Edward Bonaventure sunk off Aberdour Bay, Aberdeenshire. Chancellor and much of the crew went with them.

Wreck site of the ‘Edward Bonaventure’ off the coast of Aberdeenshire. Photo: Google Maps

The lost ships had been found and then lost again, taking much of the physical evidence of their wintering with them. Ultimately, what happened to the 63 men who wintered in Lapland in 1555 remains a mystery.