The Ninth Roman Legion, or Legio IX Hispana, was one of Rome’s elite regiments. Around 5,400 men strong, the unit spent a century in the outreaches of the empire, fighting wars and putting down rebellions. Yet this infamous military powerhouse vanished from public records after 108 AD. What became of the Ninth Legion?

The Ninth Legion’s history

When Julius Caesar became governor of Cisalpine Gaul around 58-59 BC, he acquired six legions of soldiers. Caesar used these troops in an intense campaign against locals. One of these units was the Ninth Legion, which grew in notoriety over the following decades.

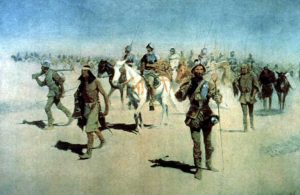

The Ninth Legion became Rome’s go-to force in key battles and for putting down rebellions. They served in the Gallic Wars, Cantabrian Wars, the battles of Dyrrhachium, Pharsalus, and Actium, and during the Roman Invasion of Britain in 43 AD.

Despite their skill, their time in Britain did not go smoothly. They experienced a humiliating defeat in 61 AD at the Battle of Camulodunum, also called the Massacre of the Ninth Legion. Led by the fearsome Iceni queen Boudicca, Celtic forces killed around 2,000 legionnaires. However, the survivors escaped, recuperated, and joined other others stationed in Germany. They continued working in York and Caledonia.

Disappearance

Historical records abruptly end in 108 AD. An inscription on a gate found in York, which turned out to be a tribute to Emperor Trajan, said, “The Emperor Caesar Nerva Trajan Augustus…built this gate by the agency of the Ninth Legion Hispana.” This is the last written record of the Ninth Legion.

Theories

Silchester Eagle in Reading Museum. Photo: Reading Museum

One long-held theory is that the Celts annihilated the Ninth Legion. British author Rosemary Sutcliff played on this theory in her bestselling novel, The Eagle. In this book (and later movie), the Ninth fell victim to the wilderness and native hostility beyond Hadrian’s Wall.

German historian Theodor Mommsen had already popularized that theory in the 1800s. He believed the Celts in northern England (particularly the Brigantes) caused the Ninth’s demise.

But despite frequent skirmishes between the Romans and Celts, no supporting physical evidence ever materialized. The only tenuous piece of evidence comes from a vague correspondence between an ancient historian named Fronto and emperor Marcus Aurelius. In their letters, they described the strength of the Celtic forces and how many Roman soldiers lost their lives. Mommsen estimated the Ninth’s destruction at around 118 AD.

In 1866, Reverend J. G Joyce found a 15cm high Roman bronze eagle in Silchester. It dates back to the 1st or 2nd century AD and might have been attached to a larger object like a statue, or carried in procession during campaigns or official activities. An important symbol of the Roman Empire, these eagles were called Aquila. Some researchers believe that this might be the lost eagle of the Ninth Legion.

Some scholarship suggests the possibility that the Ninth’s demise led to the construction of Hadrian’s Wall in 122 AD. However, this is purely speculation.

Hadrian’s Wall was built in 122 AD. Photo: Dave Head/Shutterstock

A change of scenery?

Archaeological evidence dating back to 80-105 AD suggests that the Ninth Legion may have relocated to what is now the Netherlands. A 1959 excavation in Nijmegen found tiles and an altar bearing an inscription with the words “Ninth Legion” and “Vex Brit.”

This prompted some historians to suggest a transfer from Britain to the Netherlands. Transfers were very common. Furthermore, historian Lawrence Keppie points out that the legion had a brief period of absence around 105 AD.

Another theory suggests that the Bar-Kokhba Revolt around 132 AD caused the Ninth’s demise. At that time, Julius Severus took a few European-based legions to Judea to stamp out an uprising. The revolt began because the Romans erected a pagan temple on the Temple Mount. However, the exact legions involved aren’t specified.

Fragment of an inscription bearing the Ninth’s name. Photo: Yorkshire Museum

Other researchers propose that the Ninth was active until 162 AD. As with the other theories, the evidence is thin. The ancient historian Cassius Dio claimed that the Parthians decimated an unnamed legion in Elegeia. Proponents of this theory also point to Marcus Aurelius’s construction of two columns bearing the name of each Roman legion, on which the Ninth Legion was notably absent. This could mean two things: Either the legion was wiped out, or it was disgraced through mutiny, betrayal, or desertion.

Lastly, historian and archaeologist Simon Elliot speculates that several skulls found outside London may indicate that the legion might have transferred from the northern territories before meeting their end in London.

The takeaway

Decoding ancient historical sources can be tricky, but the Ninth Legion likely died fighting. While desertions and mutinies did occur, it is unlikely that the Ninth, with a fearsome reputation and long history, would commit such betrayal.