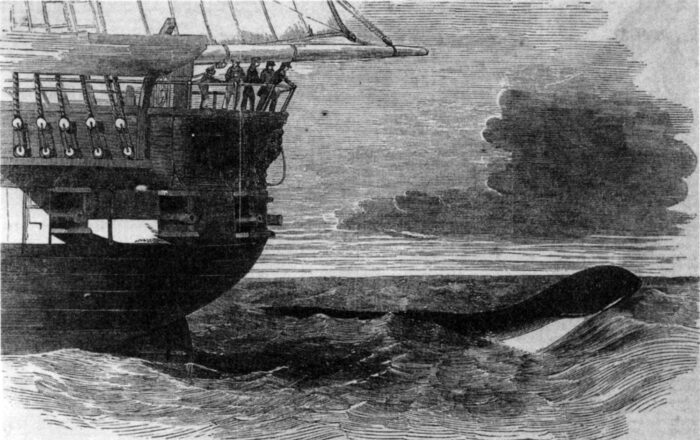

For decades in the 19th and even early 20th centuries, sea serpent sightings were commonplace. Most famously, the crew of HMS Daedalus supposedly watched one for more than 20 minutes in 1848.

HMS Daedalus and the sea serpent. Illustration: Ellis, R., 1998

The sighting

HMS Daedalus was a 19-gun Royal Navy frigate. It had seen action in the American and French Revolutions and was stationed in the East Indies for a time. Now it was bound for Britain, requiring a stop in St. Helena to resupply and deliver dispatches en route.

Not long after leaving the Cape of Good Hope, the crew spotted a storm brewing in the distance, a barrage of dark clouds on the horizon. Suddenly, their storm preparations were interrupted by a mysterious visitor in the water below. The Daedalus’s captain, Captain McQuahae, gave a detailed report of the exact moment he spotted the serpent.

A sea-serpent of extraordinary dimensions having been seen from Her Majesty’s Ship Daedalus, under my command, in her passage from the East Indies. I have the honour to acquaint you, for the information of my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, that at 5 pm, on August 6 last, in latitude 24°44′S and longitude 9°22′E, the weather dark and cloudy, wind fresh from the NW, with a long ocean swell from the SW, the ship on the port tack, heading NE by N, something very unusual was seen by Mr. Satoris. It was discovered to be an enormous serpent, with head and shoulders kept about 4ft constantly above the surface of the sea. There was at the very least 60ft of the animal.

The crew saw the serpent swimming around their vessel for over 20 minutes. It was partially covered in seaweed, had a mane, and was dark in color, except for yellow around the throat. It did not seem hostile, but curious.

Many witnesses

It wasn’t just the captain who spotted the creature; the entire crew did. None of them had previously seen anything like it. Crewman E.A. Drummond, whose written accounts were discovered many years later, further confirmed the sighting with descriptions and sketches:

The appearance of its head, which, with the back fin, was the only portion of the animal visible, was long, pointed, and flattened at the top, perhaps ten feet in length, the upper jaw projecting considerably. The fin was perhaps twenty feet in the rear of the head, and visible occasionally. It pursued a steady undeviating course, keeping its head horizontal with the surface of the water, and in rather a raised position, disappearing occasionally beneath a wave for a very brief interval, and not apparently for purposes of respiration.,

The crewmen swore this was a sea serpent of myth and legend. The Royal Navy was officially neutral, and surprisingly did not attempt to suppress or discredit the account since McQuhae was a respected captain.

Captain McQuahae published his report and a sworn statement in The Times of London. Victorian Britain was obsessed with the supernatural, and the article — accompanied by several illustrations of the ship and a large eel-like creature — gained notoriety.

Sei whale feeding. Photo: NOAA/NEFSC

More sailors came forward with sightings. In 1857 and 1860, other sightings off St. Helena and Bermuda featured similar details. Some readers were convinced. Others, not so much.

Opposition

Two figures sought to discredit Captain McQuahae’s story: Richard Owens, a renowned naturalist, and Charles Darwin. According to historian Brian Regal, Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, wrote an excited letter to Owens seeking his opinion on the sea serpent. He did not get the answer he was looking for.

Owens believed it was a sea lion, thus earning him the nickname “the sea-serpent killer.” Owens emphasized that his skepticism came from a lack of physical remains to study. Meanwhile, Darwin mocked the sighting. Captain McQuahae did not retract his statement, despite the criticism.

Theories

Did the sailors see an extinct species? What about an optical illusion? On calm seas, heat and light can distort shapes. Though the weather was about to get rough, the seas were calm.

Perhaps the crew saw an oarfish, also known as the doomsday fish. Oarfish are the world’s longest bony fish, capable of growing to 11m or more. Their long bodies resemble ribbons and undulate as they swim, creating motion reminiscent of a sea snake. The oarfish has a prominent dorsal fin that runs the length of its body, and some species feature elongated red filaments on their heads. The fin might have been mistaken for the “mane” in the 1848 account.

Giant oarfish illustration. Photo: Shutterstock

Scientists first described oarfish in the late 1770s, but they are rare and not well known. The oarfish is a deep-sea species, only rising to the surface when sick, injured, or dying. Given that 19th-century sailors had no familiarity with such a fish, it’s reasonable to assume that an oarfish would seem otherworldly to them.

Another theory comes from writer Gary J. Galbreath with the Skeptical Inquirer, who proposed it was a feeding sei whale. When a sei whale feeds, its yellow baleen plates show, which could account for the yellow the sailors noted. He also argues that the sailors might have been confused by the low, flat dorsal fin as opposed to the “stereotypical cetacean dorsal fin.”

The takeaway

Greek, Norse, Mesopotamian, and many other ancient cultures spoke of encounters between vicious serpents and heroes or ordinary sailors. Sailors routinely encountered strange sights — breaching whales, giant squids, bizarre carcasses, bioluminescence — which they interpreted with limited biological understanding. These experiences were often dramatized in taverns and port cities, giving rise to larger-than-life stories that became maritime folklore.

However, historians conclude that these stories were either founded on sightings of unfamiliar species or were symbolic stories connected to their religious beliefs. In the case of the HMS Daedalus, the sea serpent could well have been an oarfish or a type of whale.