Around the world, a handful of age-old manuscripts have baffled cryptographers and linguists for centuries. Who wrote them? Why were they made? But most of all, what are they? Below are five of the most intriguing.

Voynich Manuscript

Probably the Godfather of all puzzles, the Voynich Manuscript remains nowhere close to a solution. This odd text owes its name to Wilfred Voynich, a Polish antiquarian who owned a rare book business in the early to the mid-20th century. He purchased the manuscript from a Jesuit college in Italy.

Voynich tried to sell it for many years but he died before anyone bought it. It passed on to his wife Ethel, and then his former secretary, Anne Nill. She sold it to Hans Pete Kraus. He also tried unsuccessfully to sell it but eventually donated it to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University in 1969.

Early therapeutic bathing? Women in a communal pool. Photo: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library/Yale University

Carbon dating analysis found that the manuscript originated somewhere between 1404 and 1438. There are 240 vellum pages of an unknown script or cipher, as well as accompanying drawings of unidentified plants, astrological symbols, and naked women bathing in strange green water.

A letter hidden under the manuscript’s cover tells us something of its provenance. The letter, dated 1665, is from Jan Marek Marci to Athanasius Kircher. Marci was a Bohemian physician, while his friend, Kircher, was a Jesuit polymath.

In this letter, Marcy states that the manuscript once belonged to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II. He was known for his disinterest in state affairs and interest in academic subjects. He likely bought the manuscript from English astronomer John Dee for 600 ducats in 1586 (about $9,000 today). Rudolph believed that renowned English philosopher Roger Bacon was its author.

Some of the many plant sketches. Photo: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library/Yale University

The manuscript contains 113 plants that have not been properly identified, including star-like flowers in the margins and 100 types of herbs. Overall, there are too many oddities to make proper sense.

Some believe that the text might be a medical book for women’s health or general hygiene. There is a theory that the images of the naked women bathing indicate the Jewish tradition of mikvah, a ritual purification that a woman undergoes after childbirth or menstruation. Another theory suggests that the language is a form of Hebrew or Latin, but no evidence has confirmed this. Claims of an artificial language remain unsubstantiated.

Liber Linteus

The Etruscan civilization that preceded the Roman Empire is one of the most mysterious in the world. After the Romans conquered them, the Etruscan culture gradually disappeared. They either died, were assimilated, or relocated to other parts of the Mediterranean and North Africa. Little is known about them, apart from inscriptions on tombs, small artifacts, gravestones, and some accounts from historians of the ancient world. The Etruscan language is an even greater mystery.

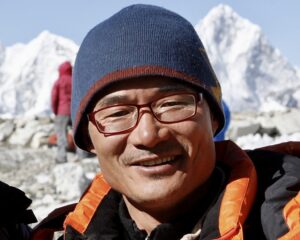

Photo: Lanena Knjiga

In the mid-19th century, a Croatian official named Mihajlo Baric was traveling through Alexandria, Egypt, and took home a sarcophagus containing a female mummy. He kept it in the sitting room of his home for all to see. Eventually unwrapping the mummy, he found its linen strips covered in text.

He did not think much of it at the time, not knowing that his delightful souvenir was actually a major contribution to the world’s understanding of the Etruscan language. After Baric died, his brother donated the linen to the State Institute of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia.

It dates back to the 3rd century BC and is currently the longest Etruscan text ever found. The linen contains 230 lines of text, divided into 12 columns. The mummy herself is from the 1st century BC.

At first, scholars initially believed it was a transliteration of the Book of the Dead into Arabic. But in 1891, it was confirmed that it was, in fact, Etruscan. Going by the few words that scholars know, we assume that the text outlines Etruscan funerary and religious practices. The language is somewhat repetitive.

Where the story gets really weird is that the mummy came with a papyrus stating the mummy’s identity. She was Nesi-Hensu, the wife of a tailor. Mummification wasn’t just for pharaohs. Common people were sometimes mummified too, especially after 2000 BC. But how did an Etruscan linen text end up on an Egyptian mummy?

There is evidence that the Etruscans lived and traded in Egypt. The Etruscans actually sold linen to Egyptians, so it is possible that the same linen was used in the Egyptian mummification process. As for why the wrapping has Etruscan text on it, it may have been the only linen available at the time.

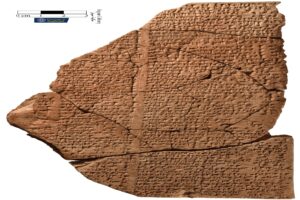

The Copper Scroll

The Copper Scroll is one of the famous Dead Sea Scrolls, found in the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine. Unlike the other Dead Sea Scrolls, which are parchment, the Copper Scroll is 99% copper and 1% tin. Bedouins discovered it in 1952.

Most scholars range the origins of the scroll from 25 to 75 CE. Its contents differ greatly from the religious and literary traditions of the others. It is written in an unknown form of Hebrew and includes Greek words and letters. While the dialect is exceedingly strange, scholars figured out that the scroll is most likely an inventory of the temple’s treasures and where they are buried. This temple is likely the Second Temple (aka Herod’s Temple). It provides 64 locations scattered throughout Judea of hiding places housing hoards of silver and gold. The estimated value of this treasure today is US$1 billion.

The main questions are, why was this important information chiseled into copper and why was it hidden? The popular theory is that the scroll was hidden to protect the treasure from Roman forces. Jewish revolts against Roman occupation were taking place from 66 CE to 70 CE. This would have prompted the Jews to protect their sacred gold and silver, in case the Romans decided to destroy Jerusalem and its temple.

Jerusalem was indeed destroyed in 70 CE. Many Jews fled in the process. It is very likely that copper was used so this information would not be lost to them, so they can build a new temple in the future.

Until now, no treasure has been found.

Rohonc Codex

In 1743, librarians in a library in Rohonc, Hungary (now Austria) cataloged an unassuming leatherbound book. They considered it a simple prayer book. Years later, in 1838, a Hungarian noble named Gusztav Batthyany gave his collection, including the prayer book, to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

In the 1840s, Europe was undergoing the Springtime of the Peoples, a series of revolutions that brought forth a renewed sense of nationalism. Interest in historical documents revived, as Hungarian nationalism gained traction. Many wanted to learn more about Hungary‘s past through such old manuscripts.

Scholars eventually realized that this was no ordinary prayer book. The book was a 448-page enigma of 90 Christian, Islamic, astronomical, and pagan images, alongside indiscernible text. Its authorship and previous ownership are unknown. Some pages are missing and arranged oddly. However, researchers determined that it was made in the 16th century in Italy.

Copy of the Rohonc Codex. A codex is an ancient manuscript in book form. Photo: Klaus Schmeh

What language is it? Popular theories include Sumero-Hungarian, Daco-Romanian, or Sanskrit. It might be a form of shorthand or complete gibberish. The images combine different religions and esoteric beliefs. It could be a message of harmony among different peoples.

A historian named Karoly Szabo accused Samuel Literati Nemes, an antiquarian and infamous forger at the time, of creating the text. However, there lacks evidence for this claim. Also, the first known record of the codex was in 1743, which takes Nemes off the list of possible perpetrators.

The Rohonc Codex is intriguing not just for its mystery but because of its inaccessibility. One must get special permission to study it, which is very hard for Western academics to obtain. The government’s close watch on the text has raised many suspicions.

In 2018, there was a breakthrough. Gabor Tokai and Levente Zoltan Kiraly combined historical analyses with statistics and structural patterns to find potential syntax and vocabulary. They have begun to create a mini-dictionary with their findings. It is taking time to reveal anything significant, but this is the best development so far.

Dresden Codex

The Dresden Codex is an 11th to 12th-century text from the Mayan civilization that miraculously survived the destruction of the Spanish conquest. Its hieroglyphs tell the story of Mayan history and religion. It includes complex calculations in astronomy, and like an ancient Farmer’s Almanac, it also makes best predictions for agriculture. It is one of four surviving texts from the conquest. Thankfully, this codex was the key to understanding the Mayan language.

No one knows quite how it got to Germany in the first place. It is widely believed that Hernan Cortes gave it to Emperor Charles V as a gift. The codex then found its way into the hands of the Saxon State Library in the mid-1800s. During the Second World War, the codex suffered water damage but restoration work saved its integrity.

Dresden Codex. Photo: Alexander von Humboldt

The codex is made from amate paper and is 3.7m long. It is brightly painted in brilliant hues of blue, red, black, yellow, and green. The panels depict different subjects. The one that most interests historians is the Venus Table. It tracked Venus’s movements and thereby the Mayan’s rituals down here on Earth. The accuracy of the calculations has stunned historians.