In 1481, a mysterious figure emerged from the desert in Benghazi. The man, exhausted and delirious after having survived a monstrous sandstorm, demanded to speak to the local emir. Intrigued, the emir allowed him to relay the incredible tale of his survival and how he managed to escape the swallowing sands that every desert traveler feared.

The stranger had been driving camels from the Nile to the oases of Dakhla and Kharga. Then he met a series of misfortunes until Providence put him on the path to an unknown oasis in the Sahara, the Oasis of Little Birds, also called Zerzura.

A tall tale?

Hamid Kiela, the man who found Zerzura, was traveling with a caravan west of the Nile when a sandstorm hit. The rest of the company suffocated, but Hamid sought shelter underneath a dead camel and survived.

After the storm had passed, Hamid had more problems to worry about — mainly food and water. He began to wander the desert in a daze, preparing himself for the inevitable. He passed out, but not long after, a group of strange-looking good Samaritans offered their assistance. They weren’t olive-skinned with dark eyes like everyone else but rather fair-skinned and blue-eyed.

They brought him to a gate with a bird at the top. Inside was an incredible city of white buildings. Significantly for the time, people were not wearing Islamic dress, and there were no mosques. Giants guarded the oasis, and the king and queen were in an enchanted sleep. The guardians of the city were huge birdmen hybrids or jinn.

Zerzura means “bird” or “starling”. Thus, it became known as the Oasis of Little Birds.

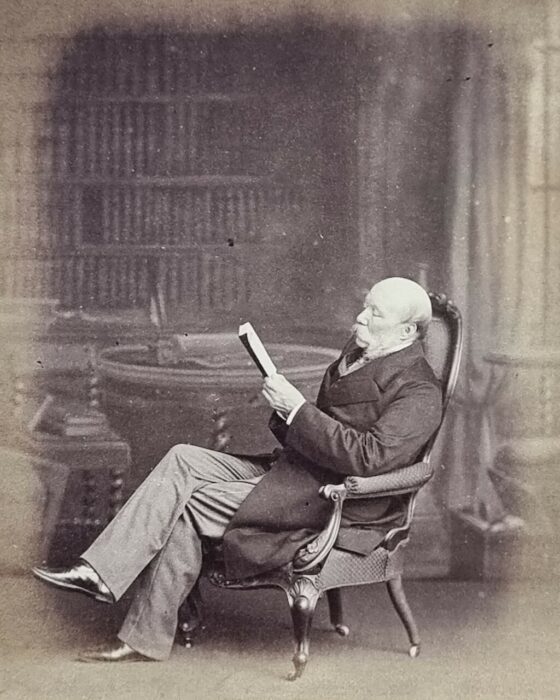

A portrait of Sir Gardner Wilkinson. Photo: State Library of New South Wales

Asked by the emir why he didn’t stay in this idyllic oasis, Hamid admits that he left of his own accord. Eventually, Hamid showed the emir a regal-looking ruby ring, implying that he had stolen it. The emir punished him but still sent out search parties to find the oasis, to no avail.

Interestingly, local legend says that the stolen ring, supposedly from Zerzura, sat on the finger of King Idris of Libya.

Book of Treasures

Our tale begins with an Arabic manuscript dating to the 15th century, now lost to us. It was called the Kitab al Kanuz, the “Book of Treasures” or “Book of Hidden Pearls”. It was a codex of over 400 treasure sites in Egypt, had a general compendium of fables and Arabic myths, and included magic spells for various purposes.

One of the stories in this Book of Treasures involved Zerzura. Fragments of this text emerged in 1904 when pieces showed up in an English newspaper based in Cairo called the Egyptian Gazette:

Account of a city and the road to it, which lies east of the Qala’a es Suri, where you will find palms and vines and flowing wells. Follow the valley till you meet another valley opening to the west between two hills. In it, you will find a road. Follow it. It will lead you to the City of Zerzura.

You will find its gate closed. It is a white city, like a dove. By the gate, you will find a bird sculptured. Stretch up your hand to its beak and take from it a key. Open the gate with it and enter the city. You will find much wealth and the king and queen in their palace, sleeping the sleep of enchantment. Do not go near them. Take the treasure and that is all.

European interest

The first mention of Zerzura by a European was in 1835 by Gardiner Wilkinson, the father of British Egyptology. He met a man who had lost his camel in the desert. The man claimed to have survived after finding a miraculous oasis five days west of the Farafra-Bahariya caravan route. He called it Wadi Zerzura and said it contained shady palms, refreshing springs, and some peculiar ruins.

An oasis in Libya. Photo: Shutterstock

For several years, the Book of Treasures was allegedly in the possession of a member of the Royal Geographic Society named E.A. Johnson Pasha. When the explorer William Joseph King Harding was trying to pinpoint the origin of the Zerzura story, he met with Johnson Pasha. Pasha told him that he possessed the only copy of a manuscript with the routes to Zerzura and other legendary locations, such as the mines of the great Persian king Cambyses. Harding searched for the city in 1909 and 1911 but found nothing.

The Royal Geographic Society published a series of papers and expedition reports related to Zerzura. They described the lost city as a “problem” that needed solving, not just because they did not know its whereabouts but because they believed it played a key role in an ancient expedition.

Richard A. Bermann, in a paper from 1934, explained their thinking. “The famous expedition of King Cambyses’s army against the oasis of Jupiter Ammon could hardly have been planned if the existence of water somewhere in the middle of the desert had not been known. Throughout the Middle Ages, Arab writers had told about a hidden oasis, the name of Zerzura,” he wrote.

Local legends

Harding also heard from locals who claimed to have seen the giant men and animals who hailed from Zerzura or had met residents who emigrated from there. But he heard conflicting reports about the state of the oasis city. Rather than the flourishing, rich city from the Book of Treasures, he often heard of an abandoned oasis. He started to believe that there were dozens of these through the desert.

The Zerzura mystery even inspired the formation of a Zerzura Club. Founded in 1930 by British explorer Ralph Bagnold (famous for crossing the Libyan Desert from east to west), the club had 13 members dedicated to finding the city. It lasted till at least 1935.

A separate group tried to find the city in 1932. Laszlo Almasy, Robert Clayton, pilot H.W.G.J. Penderel, and surveyor Patrick Clayton used planes to scout the desert. They came across lush valleys in southeast Libya containing prehistoric art. Some locals even suggested that the valley belonged to Zerzura.

Theories

There is precious little information about Zerzura, even compared to other mythical places. Take Iram of the Pillars. It was built by a king named Shaddad for the people of Ad. The city was an opulent paradise that grew too greedy, leading to its destruction.

Zerzura does not seem to be an allegory; there is no obvious moral lesson. We have no archaeological evidence to work with either, merely the fanciful words of a story.

The details about the lack of Islam in the city are peculiar. Was it a sort of commune of non-believers? Was that why the location was such a secret?

Or perhaps it was not ancient or Islamic at all. Travelers passing through might have established the oasis. Many non-Muslims traveled through the Sahara, particularly in the medieval period. It could have been a foreign group living in this oasis that did not adhere to Islamic customs. Additionally, they were fair-skinned and blue-eyed, which indicates a European background. The Crusades lasted until 1291. Were these Crusaders that settled in the desert? The mystery endures.