Archaeologists have long studied rock art to determine the underground movements of early humans. They know humans were there, but not how man made these remarkable journeys into the darkness. A new paper published last month has shed light on how humans explored deep inside the Etxeberri cave system in the Western Pyrenees 16,000 years ago.

Using laser scanning, 3D modeling, mapping, and archaeological evidence, Spanish researchers have pieced together how they believe Magdalenian people (Late Palaeolithic hunters and artists) navigated this challenging cave system, described as one of the most extreme examples of prehistoric caving.

The Etxeberri cave system

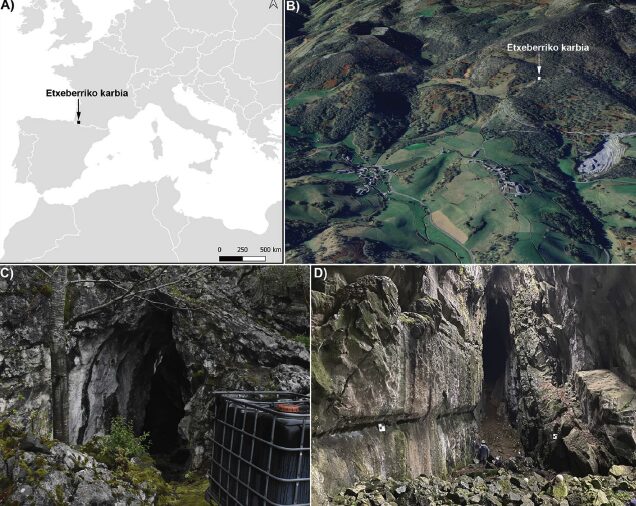

The Etxeberri cave system lies in the French Pyrenees at 448m and was largely unexplored until the 1930s because of its complexity. Cavers needed modern caving equipment such as powerful lighting, ropes, anchors, and protective gear. Somehow, prehistoric artists journeyed deep into the Etxeberri without any of this.

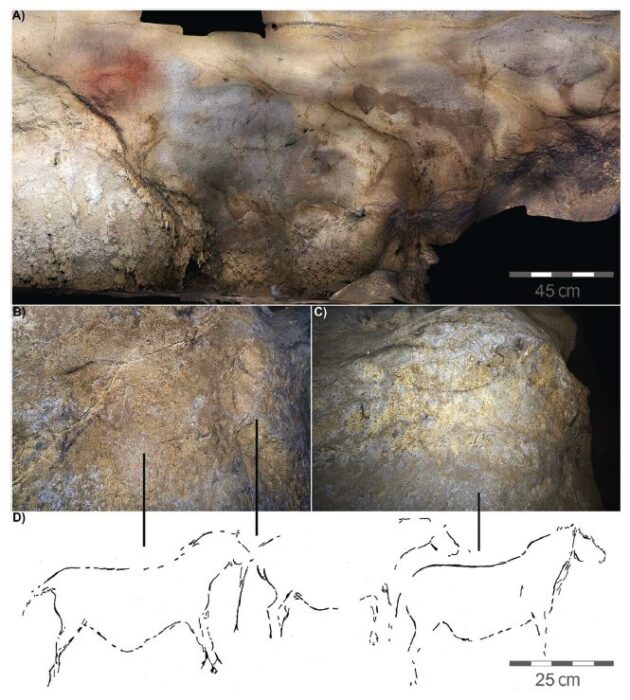

In the 1950s, cavers found a painting of a small red horse on their way out of the cave. In the ensuing decades, cavers have discovered 77 pieces of rock art, including depictions of horses, bison, ibex, and abstract drawings.

Archaeologists reckon that these were painted using charcoal or clay, sometimes mixed with crushed bone. Other markings may have been engraved into the soft cave walls.

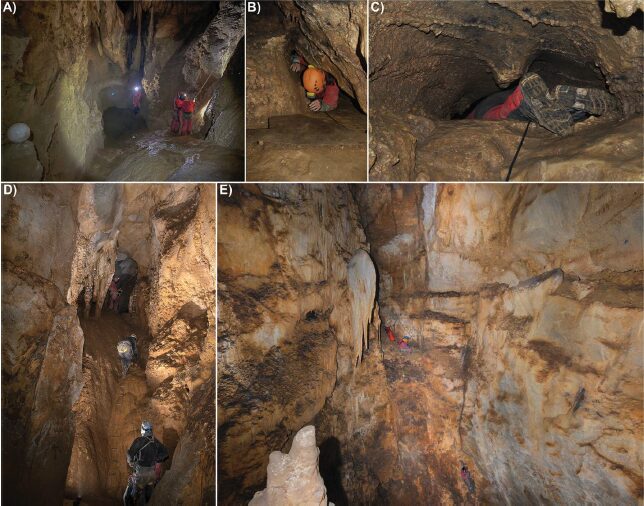

The complexities of the Etxeberri cave system are apparent even for modern cavers. Photo: Iñaki Intxaurbe, Diego Garate, and Martin Arriolabengoa

A difficult descent

To reach the deepest parts of the cave, prehistoric artists faced a host of difficulties. Around 90m from the cave entrance, there are underground lakes which flood during wetter periods. Beyond that, there is a tight crawl way which opens sharply into a two-meter drop to the “Hall of Paintings.”

Further into the system, a 7m drop leads to the “Room of the Sinkhole.” At the farthest point from the entrance, a 16m sinkhole dubbed the “Sinkhole of the Angel” lies surrounded by a perilous ledge where ancient people have engraved horses.

The rock art is concentrated in two places. The first is the Hall of Paintings, a relatively accessible and open chamber where the images are easy to see, likely serving as a more public gallery. Cavers found the second collection in decorated fissure and sinkhole zones, which are extremely difficult to reach, narrow, and hazardous. Here, only a few people could have viewed the figures at a time, suggesting these spaces were reserved for private or ritual activities.

A) In the Hall of the Paintings, a red horse, a goat, a bison, and another horse appear alongside lines and smudges. B–C) In the Decorated Fissure, two horse figures are now almost erased by modern cavers’ activity. D) A 1950 drawing shows the same animals when they were still sharp and clear. Photo: Iñaki Intxaurbe, Diego Garate, and Martin Arriolabengoa

How did they get down there?

The team of archaeologists used high-resolution scanning devices and analysis of the spaces within the cave, as well as pigment stains and tool fragments, to reconstruct the routes the Magdalenian cavers likely followed.

They also simulated the lighting the Magdalenian cavers may have used and estimated average body sizes at the time to determine the movements required (e.g., crawling).

Three-dimensional reconstructions of how the Magdalenian cavers might have moved through the cave system. Photo: Iñaki Intxaurbe, Diego Garate, and Martin Arriolabengoa

The resulting analyses suggested that the early rock artists broke obstacles such as stalagmites using flint tools, chimneyed (pushing against both walls) down vertical drops, crawled through tight passages, slid down shorter drops, and edged along exposed ledges.

Though there is no evidence of the Magdalenian using rudimentary ropes, the Spanish researchers didn’t rule out the possibility, given that rope remains rarely survive 16,000 years of decay. The researchers did cite possible corrosion marks near a ledge as an indication that people may have used a wooden beam to anchor a rope. To light the way, researchers suggest that the Magdalenians used torches made from juniper, pine, and even bone.

Why risk it?

The presence of rock art and the hazardous nature of these subterranean adventures suggest that the Magdalenian weren’t looking only for shelter or safety. Instead, the caves seem to have symbolic and spiritual importance. Descending the cave would have taken courage, planning, cooperation, and technology (early torches).

Location of the Etxeberri cave system. Photo: Iñaki Intxaurbe, Diego Garate, and Martin Arriolabengoa

This example in the Etxeberri is a remarkable reminder that adventure is ancient. Sixteen thousand years ago, artists braved darkness and danger not for survival, but for meaning, just as the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) later scaled sheer cliffs to build their dwellings in the American southwest. The urge to explore extreme places above and below ground runs deep through human history.