When phosphate miners in Morocco accidentally uncovered a fossil in 2021, it seemed too good to be true.

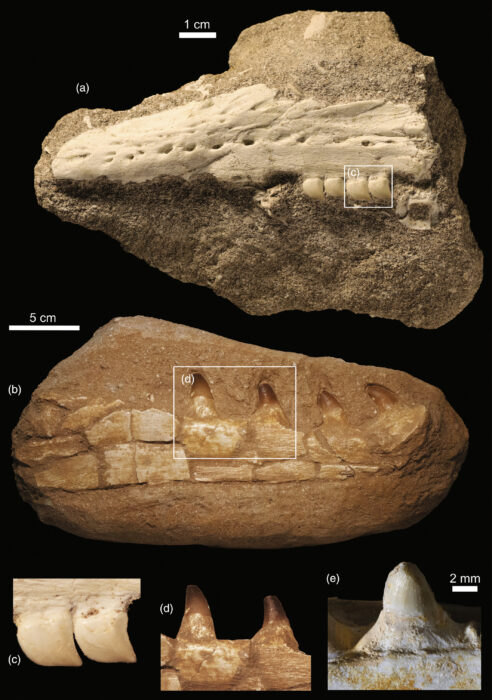

Nick Longrich, a paleontologist from the University of Bath, examined the jawbone and four teeth, then wrote a paper describing the fossil as belonging to a new species of mosasaur — a large carnivorous marine reptile that lived during the Cretaceous period. He published his paper in 2021, and it made waves in paleontology circles.

Unfortunately, things that seem too good to be true usually are. That could be the case with the mosasaur fossil, according to a study published last month in the journal The Anatomical Record.

In the 2021 paper, Longrich and his co-authors pointed to the unique arrangement of the fossil’s teeth as evidence that it belonged to an unknown species of mosasaur. Longrich dubbed the find Xenodens calminechari. Every other known mosasaur fossil has one tooth per tooth socket. X. calminechari has two teeth per socket.

A graphic from Sharpe’s paper compares and contrasts the Xenodens calminechari fossil with a known forgery. Photo: Longrich et al., Sharpe et al.

A second look

This odd fact, combined with the jaw’s discovery in a region known for producing fossil forgeries, prompted Henry Sharpe, a researcher at the University of Alberta, to do a little additional peer review.

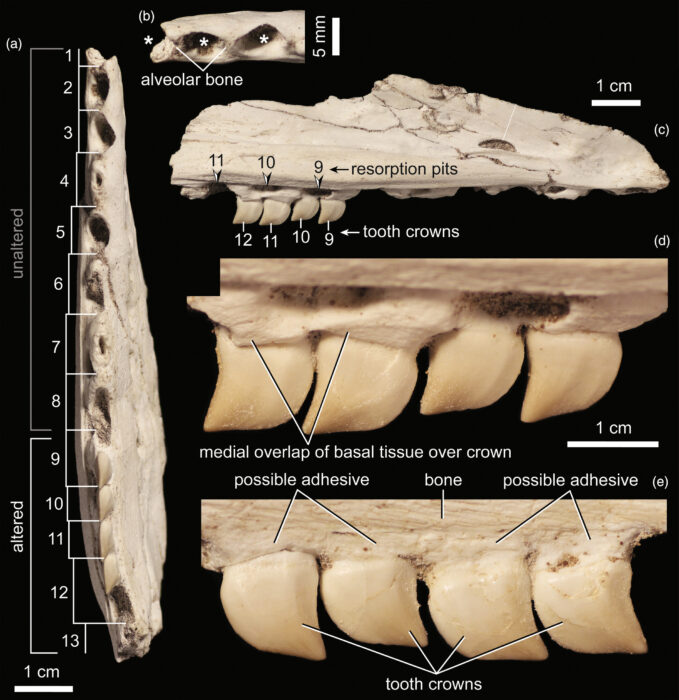

A final troubling note — two of the teeth have a little extra bone material intruding on them, a feature called “medial overlap.” That’s not typical for mosasaurs at all, Sharpe’s team noted in its paper.

“The fact that there’s that medial overlap is a huge indicator” of a possible forgery, Mark Powers, study co-author, told Live Science.

Fake fossils are big business in Morocco. It has some of the world’s richest fossil beds, and more than 50,000 people make a living in the fossil trade.

As Sharpe and his team point out, there’s a relatively simple way to prove the fossil is legit — subject it to a computed tomography (CT) scan. But Longrich wasn’t too happy about that prospect.

This graphic from Sharpe’s paper uses a photograph from TK’s paper to demonstrate potential clues about the fossil’s possible forging. Photo: Longrich et al, Sharpe et al.

Extremely gauche

According to Sharpe, Longrich asked him if his team was writing a paper on the fossil, and “if so, what’s the angle of that paper?” Then he denied Sharpe’s request for a CT scan.

Longrich’s reaction “raised immediate red flags,” Sharpe said. Sharpe was especially upset because the Morocco fossil is a new species. In scientific circles, it’s considered extremely gauche to withhold access to new species.

“That’s totally unethical that he would even request that,” Sharpe said.

Sharpe and his co-authors finish their paper by formally suggesting the Morocco fossil be subjected to a CT scan. As to whether pressure from the scientific community will cause Longrich to change his mind — that remains to be seen.