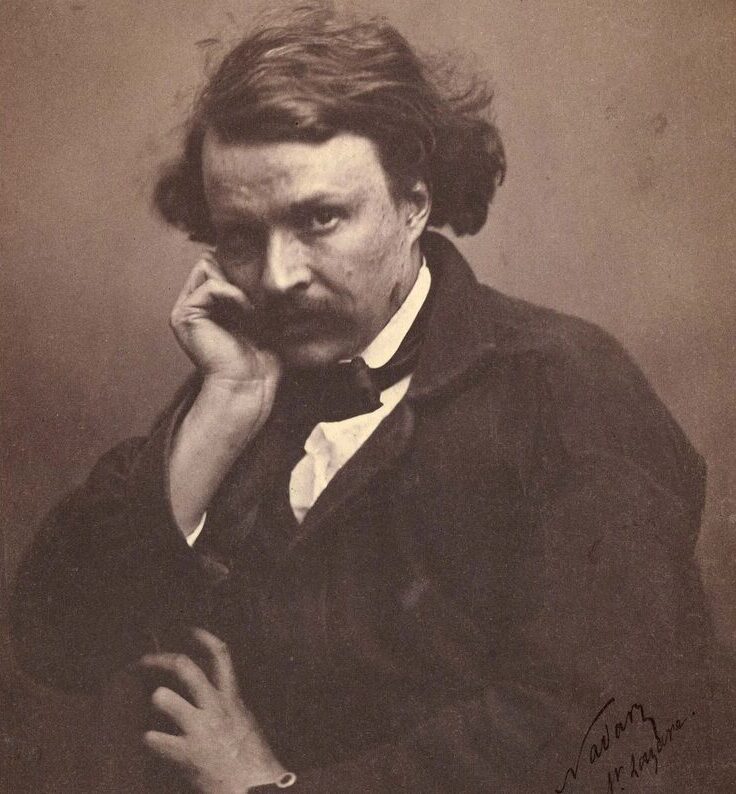

The first person to take both aerial and subterranean photos, Gaspard-Felix Tournachon, alias Nadar, was a pioneer of both ballooning and photography. He thrilled the French public with his daring flights above and his explorations below in the Paris Catacombs. He published the first photo interview and established the first airmail service, surviving a catastrophic crash along the way.

A self-portrait of Nadar, currently held in the Getty Museum.

The origin of Nadar

Born in Paris in 1820, Gaspard-Felix Tournachon came of age as the peaceful and prosperous Bourbon Restoration period ended and an era of political turbulence and intermittent revolutions began. Gaspard-Felix moved to Lyon as a teenager in order to study medicine. However, when he was 18, his father’s publishing house went bankrupt.

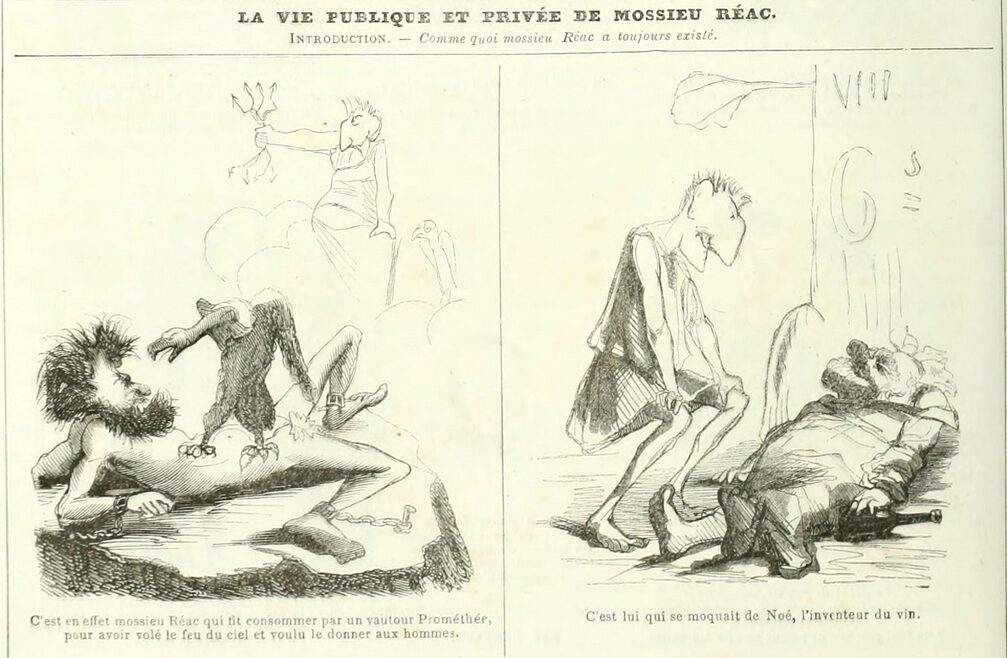

Forced to make his own way, he reinvented himself as “Nadar” and began writing newspaper articles under the mononym. A childhood nickname that punned on his surname, his choice of a simple, unique moniker shows his flair for branding. By 1842, he had moved back to Paris and began publishing caricatures in popular satirical magazines.

“In fact, it was Mr Reac who made Prometheus be consumed by a vulture, for having stolen the celestial flame to give to humanity. It was he who mocked Noah, inventor of wine.” Mossieu Reac was a satirical character who appeared frequently in Nadar’s work. Photo: La Revue Comique, 1848

His crowning achievement was what he called his Pantheon, a sprawling lithograph of nearly 250 caricatures of contemporary artists, scientists, politicians, and writers. But not long after he completed this celebrated masterwork, his mind was on the future: photography.

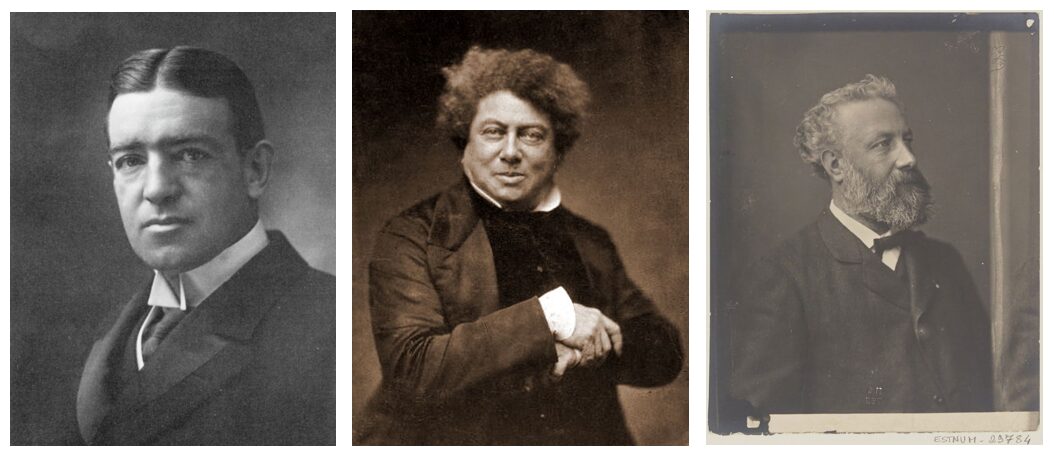

With his younger brother Andre, Nadar opened a photography studio in the center of Paris. The building, painted bright red and emblazoned with his name in massive letters, became a social hub of the artistic elite. Nadar did portraits of the biggest names of his age: Eugene Delacroix, Alexander Dumas, Emile Zola, Jules Verne, Sarah Bernhardt, both Manet and Monet, Louis Pasteur, and dozens more. Toward the end of his life, he even photographed Ernest Shackleton.

Ernest Shackleton, Alexander Dumas, and Jules Verne as photographed by Nadar. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Taking to the sky

Nadar won sole control over the studio after a messy legal battle with his brother, and he never stopped photographing the famous. At the same time, however, he began to look toward aeronautics.

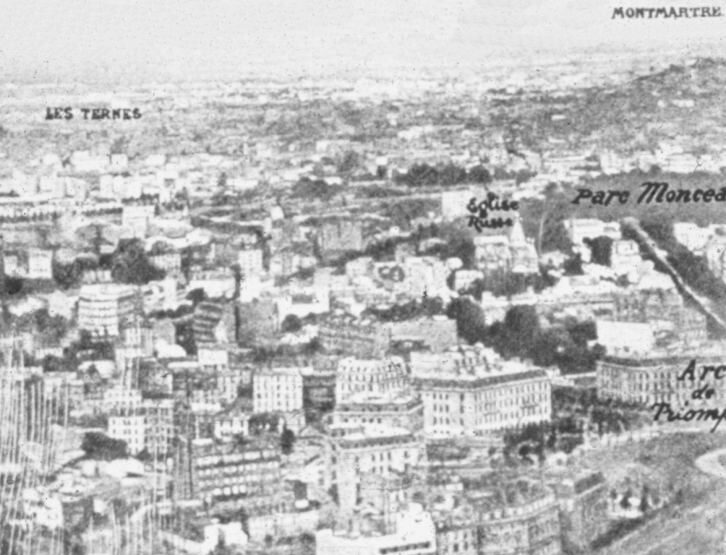

In 1858, Nadar took the very first aerial photograph, from a tethered hot air balloon 80 meters above the village of Petit-Becetre. In addition to managing a massive camera, the collodion photographic process required Nadar to construct and operate a complete darkroom from within the balloon. Also known as the wet-plate process, Nadar had only about ten minutes after the shutter clicked to coat, sensitize, expose, and develop his photograph.

The first aerial photograph in 1858 no longer survives; Nadar took this view of Paris in 1866. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The 1858 photograph was the culmination of three years of trying. Once it was done, Nadar only became more invested in aeronautics. Balloons, he had discovered, don’t steer very well. The future of flight wasn’t in the lighter-than-air, but in the heavier. How would he raise the funds to build the machines that would replace the balloon? Simple: build the world’s largest balloon.

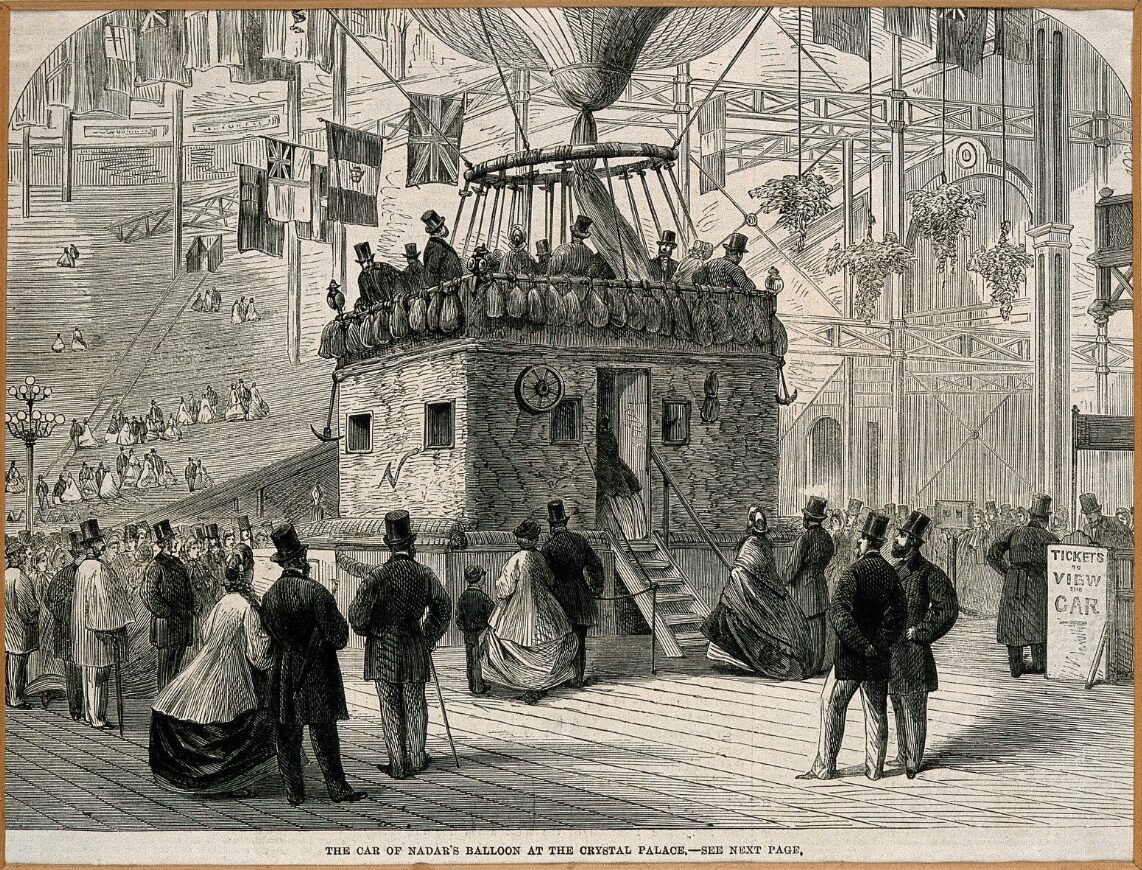

Its 60-meter height required over 20,000 meters of silk, and it took over 5,600 cubic meters of gas to fill it. Rather than a basket, it suspended an entire wicker apartment with a balcony, parlor, and full darkroom. Appropriately, Nadar named it Le Géant: the giant.

In 1863, his photography studio also became the headquarters of the Society for the Encouragement of Aerial Locomotion by means of Heavier-than-Air Machines. Jules Verne was the Secretary. That same year, Le Géant had its first flight.

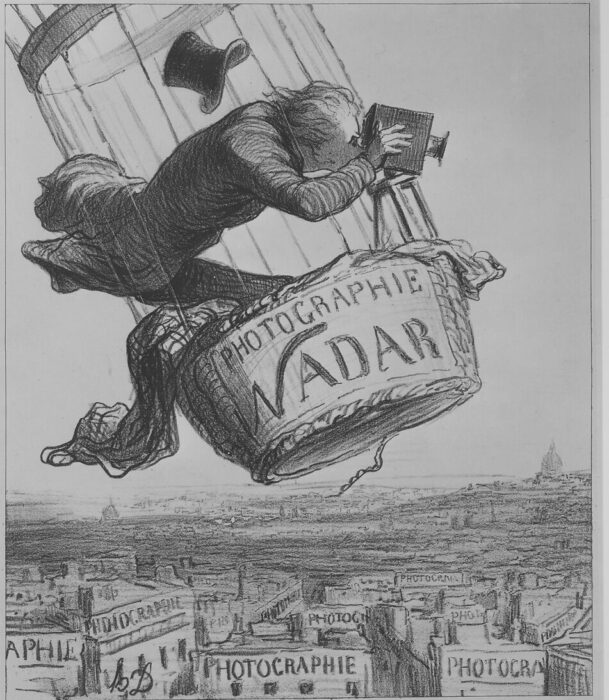

A cartoon by Honore Daumier shows Nadar taking aerial photographs over Paris. Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art

The flights of the Giant

In early October of 1863, Nadar readied for takeoff on Paris’ Champs de Mars, as a crowd of over half a million Parisians looked on. Nadar took 12 passengers, as well as the engineers of his balloon, the brothers Jules and Louis Godard. Preparations dragged on into the afternoon, and spectators were restless by the time the world’s largest balloon lifted off.

Rising 600 meters above Paris, the balloon began to glide eastward. While aloft, Nadar recorded his impressions in rhapsodical tones (“Quelle extase!”), claiming to be untroubled by the great heights. While passengers were prepared for a long trip, even bringing along their passports, the balloon descended after only 15 minutes. A valve line malfunction forced Nadar to land the balloon about 40 kilometers away.

The second flight, Nadar promised, would be better. Two weeks later, Nadar took nine passengers, including his wife and the Godard brothers, up again. Napoleon III and at least 200,000 other spectators watched the balloon leave the ground and begin drifting northeast. A few hours later, it crossed the border into Belgium. By midnight, they were over the marshes of the Netherlands, nearing the coast.

This was alarming (hint to balloonists: avoid landings in the open ocean), and they began discharging ballast until the balloon rose again. According to one passenger, the journalist Eugene Arnoult, nobody slept that night due to the anxiety.

This engraving shows the large, elaborate basket underneath the balloon. As the sign suggests, Nadar charged curious members of the public a fee to visit the basket. Photo: Wellcome Collection

Wreck of Le Géant

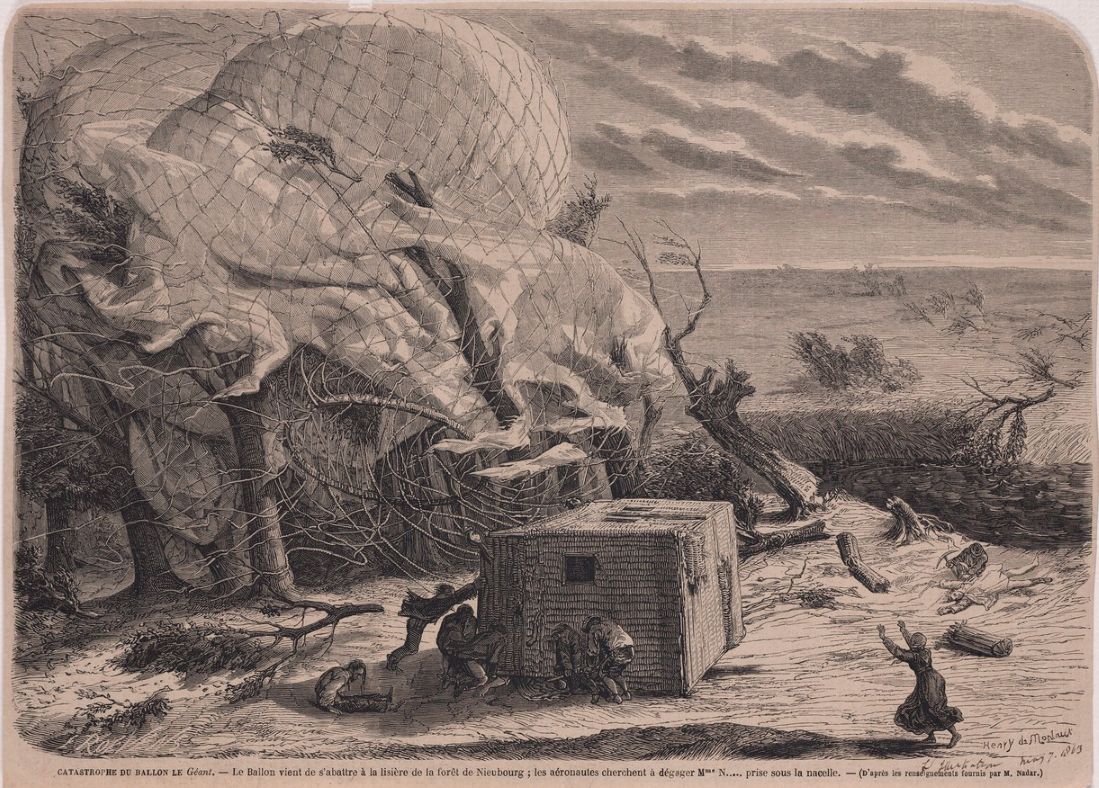

Luckily, the wind changed, and morning found them floating toward Germany. They began to sink again when a fierce gust of wind caught the balloon. In minutes, the iron anchors were broken, the valve snapped shut, and Le Géant went mad.

Descending rapidly and wildly, the balloon went sideways and flew off on a wild tear, dragging its passengers over the ground. They burst through thickets and got tangled in telegraph wires, narrowly avoiding a passing train. They swiftly approached a large house, against which they would surely be dashed to pieces. All of them seemed frozen in terror until this moment, when Jules Godard leapt into action.

He threw himself into the netting, falling several times as the whole structure careened wildly, finally reaching the valve chord and pulling it open. Now they only had to hold on until the gas was expelled. But too soon, a wooded area appeared before them. Fearing worse injury if they smashed into the trees, Arnoult jumped.

He tumbled in the air, landed on his head, and lay stunned. When he sat up, it was over; the wrecked balloon was still. Nearby, fellow passenger Saint Felix was lying with a broken arm and dislocated ankle. Nadar himself lay not far off with a broken leg, while his wife, Ernestine, had been flung into the river. Arnoult himself nearly drowned rescuing her.

All in all, they had travelled over 600 kilometers in 17 hours before crashing in Hanover. For Nadar, who had sunk most of his money into the project, it was a financial disaster.

Contemporary illustration by Henri de Montaut showing the wreck of Le Géant.

Into the empire of death

At the same time as he was experimenting with travel through the sky, Nadar was making subterranean forays. Specifically, he was exploring the world beneath Paris, an extensive network of sewers, ancient tunnels, and, of course, the Catacombs.

Built in 1810 to relieve the city’s overflowing cemeteries, the Catacombs were not the mapped, lit, and tour-guided sites you can buy a ticket for today. In his memoir, Nadar described his descent into the ossuary, which had been officially closed to the public for decades. Guided by a site worker, he descended a tucked-away stone staircase into a world of utter blackness, populated by the uncounted anonymous dead.

Nadar in the Catacombs. At his feet are arranged some of the equipment and noxious chemicals he had to haul down there to make the image possible. Photo: Gallica

In his studio, Nadar had already replaced sunlight with artificial lights (he was, in fact, the first to do so). He knew that this would be the only way to capture the macabre world beneath. To do so, he would need to generate power by linking massive Bunsen cell batteries together and weaving the wiring through the narrow passages. He also brought mannequins down into the Catacombs in order to stage strange little scenes.

A mannequin, dressed as a worker, pulls a cart full of bones, forming what we can all agree is a deeply troubling image. Photo: Gallica

The next year, Nadar descended again to capture images of the Paris sewer system. Nadar was inspired and guided by the sewers’ leading role in his friend Victor Hugo’s new novel, Les Misérables. Every famous French person in the 19th century knew Nadar.

A man of many firsts

A pioneer in many fields, we haven’t even spoken of several of his records yet. One notable incident came in 1870, when the Franco-Prussian War spilled onto the streets of Paris. For five months, Paris was under siege, completely encircled by Prussian forces. Nadar, sensing a problem that hot air balloons might solve, established the “No. 1 Compagnie des Aérostatiers,” with a single balloon named Neptune.

Neptune successfully carried mail out of the besieged city, becoming the very first air mail service. Soon, the service expanded, championed by Nadar, to 66 balloons. During the siege, they delivered over a hundred passengers and 2.5 million letters. Only five balloons were captured, and three were lost to the sea. One survived a record-breaking 1,400km journey, finally ending up in Norway.

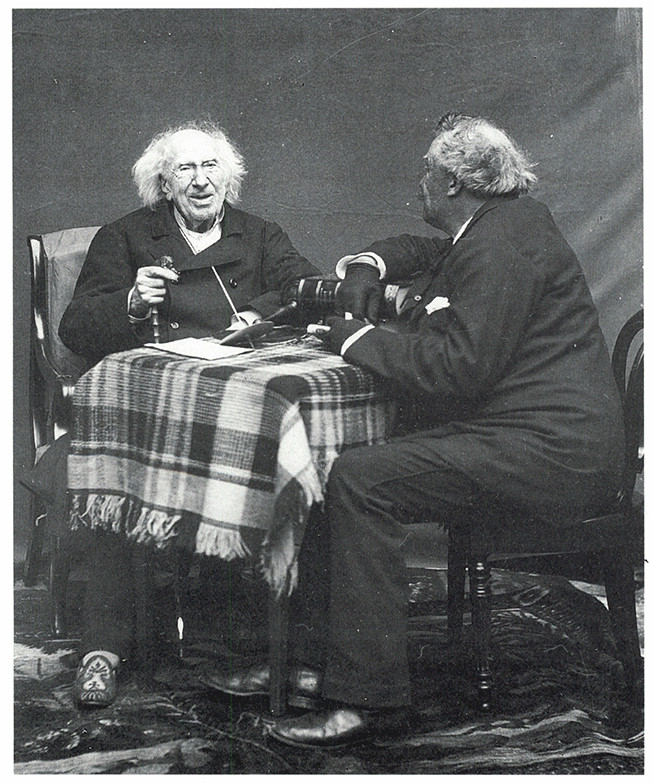

Sixteen years later, Nadar established another first when Le Journal Illustré published his article, The Art of Living to 100 Years Old. It was an interview with French chemist Michel Eugene Chevreul (inventor of the RYB color wheel, among many other accomplishments) on his 100th birthday.

The interview was printed alongside 12 unstaged photographs, taken by Nadar’s son and photographic protege Paul. It is now considered the first photographic interview.

In the caption of this image, Chevreul humorously attributes his long life to a practice of never drinking water, only Anjou wine.

Nadar himself didn’t quite make it to 100, but he did live to see the first powered flight in 1903. It had taken half a century, but he’d finally been proven right about the future of aeronautics.