Researchers have discovered evidence of the first known primate relatives living above the Arctic Circle.

They may not look much like primates, but you might not either if you lived 52 million years ago.

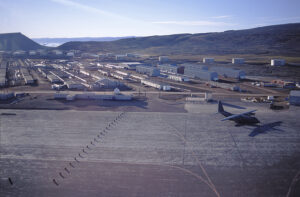

The two sister species lived on what is now Ellesmere Island in extreme northern Canada. They were somewhat smaller than house cats, one researcher told CNN. Their scientific names: Ignacius mckennai and Ignacius dawsonae.

“To get an idea of what Ignacius looked like, imagine a cross between a lemur and a squirrel that was about half the size of a domestic cat,” said Dr. Chris Beard, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas. “Unlike living primates, Ignacius had eyes on the sides of its head (instead of facing forward like ours) and it had claws on its fingers and toes instead of nails.”

Two sister species are the first known primate relatives to have lived in latitudes north of the Arctic Circle. Read more from @CNNAshley about these findings by @KU_EEB @kunhm researchers published yesterday in @PLOSONE.https://t.co/jvGrjwrIOU

— KU News Service (@KUnews) January 26, 2023

Beard told ExplorersWeb that the now-extinct animals belonged to a segment of the primate family tree that split off before the ancestors of lemurs diverged from the common ancestors of monkeys, apes, and humans.

Beard’s cohort published their findings in the journal PLOS ONE on Wednesday. In the paper, they specify that the Arctic primatomorphans (or primate relatives) developed jaws and teeth that suggest a different diet than many similar animals of the time that lived further south. Many species related to Ignacius preferred ripe fruit, according to the paper. But Ignacius could chow down on harder objects — probably as a byproduct of living through permanently dark Arctic winters.

A Louisiana climate

That’s not to say that Ellesmere Island was at the time the frozen tundra that it is today. When the species’ ancestors likely arrived there 51 million years ago, the warm global climate had made even these High Arctic latitudes swampy, with a climate similar to present-day Louisiana.

A scientist excavates a two-million-year-old beaver den, Strathcona Fiord, Ellesmere Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Throughout the years, paleontologists have found fossils of dinosaurs, Tiktalik (a “fishapod” that could crawl on land), beavers, and even primitive crocodiles, horses, and rhinos. Fossil forests of cypress and redwood — in a place that is now 2,500km north of the nearest tree — show how much the climate has changed over the millennia.

An arctic sledder hauls through Ellesmere Island’s Bird Fiord, where the ‘fishapod’ fossil was discovered. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

For Beard, Ignacius’ story parallels one we’re likely to see play out as the planet’s climate continues to change.

“[The findings] tells us to expect dramatic and dynamic changes to the Arctic ecosystem as it transforms in the face of continued warming,” he told CNN. “Some animals that don’t currently live in the Arctic will colonize that region, and some of them will adapt to their new environment in ways that parallel Ignacius. Likewise, we can expect some of the new colonists to diversify in the Arctic, just as Ignacius did.”