“I remember we were in the bunk about two or three o’clock in the morning, and somebody came into the barracks and said, ‘You’re going to South Pole at 0800’ or something,” said Conrad Shinn in a 1999 interview. “We chuckled because we thought that was what we called a whiskey decision.”

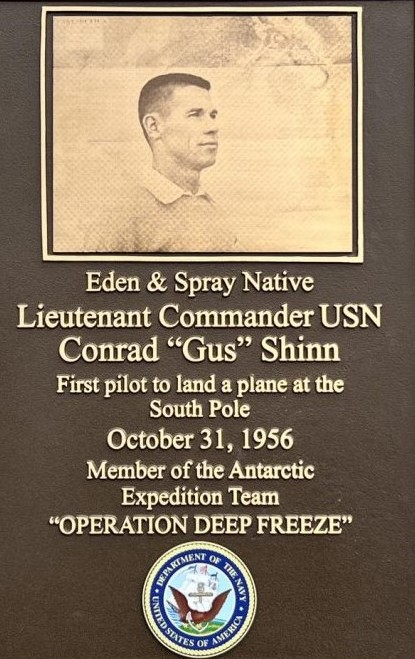

That’s how Lieutenant Commander Shinn recalled finding out he had been chosen to land at the South Pole. A WW2 veteran, Shinn joined the American Naval Antarctic exploration efforts “just to get out of doing the usual things every day.” On October 31, 1956, he became the first man to land a plane at the South Pole.

A recent announcement reveals that he died on May 15 in Charlotte, North Carolina, at the age of 102.

Mount Shinn, the third-highest mountain in Antarctica, is named for Conrad Shinn. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Test flights

The decision to send Shinn to the South Pole, he claimed, was fairly last minute. But Shinn had plenty of experience for the job. At the start of WW2, he’d joined the Naval Aviation School. After graduating, he served in the Pacific, airlifting casualties. After the war, he decided to volunteer for duty in Antarctica.

There, he worked under the famous and somewhat controversial explorer Admiral Richard Byrd. His first flights at the bottom of the world were part of Operation Highjump, in 1946-47. His job was to fly back and forth over the frozen continent, while a camera strapped to the plane took pictures.

The mission fell short of its goal — to take air photos of the continent for mapmaking — but it gave Shinn lots of experience with Antarctic aviation. As Shinn reflected in 1999, “It was fun. No, I don’t really understand why they did it and what the benefits were.”

Photo: Facebook

Shinn was part of an anti-submarine helicopter squadron in 1953, when a call went out for volunteers for a new Antarctic mission. He was the first pilot to sign on.

The new mission was part of Operation Deep Freeze, a 40-nation endeavor to explore both polar regions for science. The Antarctic aviation branch made a rocky start. In the first year, the planes didn’t bring enough gas, and half of them, including Shinn’s, had to turn around and go back to New Zealand. Aircraft carrier ships were deemed unworkable in the frozen waters. So, Shinn made his triumphant return to Antarctica only after 18 hours of difficult flying.

An aerial view of ‘Little America,’ the base established during Operation Highjump. Photo: USAP Photo Library

Que Sera Sera

By year three, though, they had not only made it to Antarctica but also set about a science program. The crowning achievement was to fly to and land at the South Pole.

Staffing the flight was complicated. As with Scott’s more ill-fated South Pole run, no one knew who would be on the final team until the last minute. There were two factions: one was aligned with the absent Admiral Byrd, the other with Admiral Dufek. Shinn, a neutral party, believed he was chosen partly to prevent a Byrd-aligned man from going.

Shinn observed more staffing drama when it came time to decide the co-pilot. The plane was a twin-engined R4D-5 Skytrain called Que Sera Sera. It could bring seven, but only two in the cockpit. When Captain Hawkes was chosen over Captain Cordiner, Cordiner protested.

“If there’d been any firearms, they might’ve been used,” Shinn recalled. “He was really livid.”

The flight out went comparatively smoothly. On October 31, 1957, eight hours after taking off from the base at McMurdo Sound, Shinn landed Que Sera Sera at 90 degrees South.

While the brass took photographs, Shinn hopped back into the plane. Landing, he knew, had been the easy part. Now came the hard part — taking off. The stakes for failure were high; they had very little survival experience and no other means of transport. It was around -50˚C. The Navy’s backup plan was to airdrop survival equipment for them.

The ‘Que Sera Sera,’ named for the popular Doris Day song. Photo: National Naval Aviation Museum

Take-off from the South Pole

The real achievement, Shinn later quipped, was being the first man to take off from the South Pole. The pole is about 3,000m above sea level. With the thin oxygen, the engines couldn’t fire at full capacity. Worse, the heat of the plane’s skis melted the ice beneath it, which refroze quickly in the freezing temperatures.

Even with the engines at full, Que Sera Sera couldn’t budge. Shinn resorted to a jet-assisted take-off. This meant firing 16 rockets in order to generate enough thrust to get them aloft. It just barely worked.

The pilot wasn’t home free. “We were engulfed in a cloud of ice,” he said, which limited visibility. The extreme cold made the instruments inaccurate, and at any moment, the hydraulics in the flaps could freeze solid.

Luck and skill held true; Shinn returned them all safe (though not sound; the Admiral had come down with pneumonia) to base.

Shinn retired in 1963 to Pensacola, Florida. When asked in the 1999 interview if he wished he’d done anything differently, he responded with a firm no. “I did my best. I had good crews.”