Feb. 6, 2021 dawned with a sense of anguish for international audiences intently following the events on K2. Three climbers were missing and another had fallen to his death just hours before. Others were still on the mountain, shocked by the unfolding drama and struggling under hellish conditions.

Two days earlier, it was clear that the next 48 hours would be crucial on K2. Almost everyone remaining in the mountain had gone up in a frenzied summit push despite less-than-ideal conditions.

While “less than ideal” seems understandable for the second-highest peak on Earth in the dead of winter, the forecast showed a short weather window on Feb. 5. However, those attempting the summit on that Friday would need to be extremely fast and run back down to lower altitudes before the winds increased on Saturday.

That was very different from the nearly perfect conditions that the Nepalese team enjoyed on Jan. 16 when they forged their way to the summit and into the history books. Animated — and in some cases frustrated — by that triumph, a variety of climbers with different levels of experience, support, and motivation embraced their last chance for a slice of winter glory.

Hours later, the climbers who reached the “higher” Camp 3 at 7,300m discovered that the weather was only one of many problems.

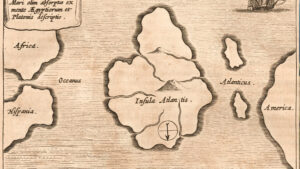

Forecast for K2 between Feb. 4 and Feb. 7, 2021, by meteoexploration.com

Dangerously behind schedule

Most of those who climbed to the higher Camp 3 were dangerously behind schedule. They intended to continue to the summit the following day and needed a few hours of rest. But they found out that C3 was too small and there were not enough tents for all of them.

Others had stopped at a lower camp right below the Black Pyramid. For various reasons, they all eventually turned around. Soon, they were glad they did.

Elia Saikaly, PK Sherpa, and Fazal Ali were among them. Their supplementary oxygen was not stocked as expected because of some miscommunication, and they had to abort.

“We listened in via radio to the chaos unfolding above at proper Camp 3,” wrote Elia Saikaly. “People were trapped outside with no shelter higher up in -70˚C temperatures. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t grateful that our plan broke.

“The events that night led to the tragic death of our friends, whom we were supposed to be filming. Years of truth-chasing ensued.”

Indeed, four people died in the following hours. They left, in addition to the tragedy of their loss, many unanswered questions. The stubborn silence of expedition leaders, the contradictory testimonies of some climbers, the general atmosphere of competition and secrecy, and the impossibility of setting a clear course didn’t help. The desperate search for the missing climbers and the national drama that ensued heated opinions even more and made the rumors fly higher. This was especially so in Pakistan, where Ali Muhammad Sadpara is still sorely missed.

What happened, as far as we know

The unquestionable fact is that John Snorri of Iceland, Ali Muhammad Sadpara of Pakistan, his son Sajid Sadpara, and Juan Pablo Mohr of Chile left Camp 3 at midnight on Feb. 4-5. Other climbers at Camp 3 tried, but no one else was able to find the way around a wide crevasse.

The Nepalese who summited (and fixed the ropes) weeks earlier had faced the same problem. They had been forced to retrace their steps and deviate until they found a suitable passage across the gap and toward the upper sections.

Why the second wave of climbers and their sherpas heading for the summit was incapable of picking the right route is unclear. Sajid Sadpara reported that his group also followed the ropes to the mouth of the crevasse and walked for a significant time until they found an exposed but climbable passage.

Left to right: Sajid Sadpara, John Snorri, and Ali Muhammad Sadpara in Base Camp. Photo: Elia Saikaly

A lucky problem

The young Sadpara didn’t follow the group much longer. His oxygen system wasn’t working properly, and his father told him to go back to Camp 3. That was the last time Sajid saw his father and the others alive. John Snorri’s tracker stopped sending a signal at the crevasse, but their cook in BC said he had spoken to him at around 4 pm. At this time, Snorri told him that they were at 8,300m.

As the sunny morning came, defeated climbers in Camp 3 began to head down. One of them, Atanas Skatov of Bulgaria, was walking down confidently, apparently not clipped to the ropes. Suddenly, his foot slipped and he fell into the void in front of his supporting sherpa, Lakpa Dendi.

Atanas Skatov and Lakpa Dendi as they went up to K2’s Camp 3, in one of Skatov’s last pictures.

Tamara Lunger of Italy was among the last to retreat from Camp 3. She waited for Juan Pablo Mohr until cold and the menacing forecast pushed her back down. At the end of the day, Sajid was the only living soul at 7,300m, stepping out of the tent from time to time, worried sick, and hoping in vain for a radio message or the light from headlamps.

The search

By Feb. 6, the alert sounded and the first helicopter explored the slopes of K2 for the missing climbers. Lunger reached Base Camp that day. Seven Summit Treks’ expedition leader Chhang Dawa Sherpa needed hours to convince Sajid to retreat and save himself. The young Pakistani finally agreed and returned to Camp 1 that day.

The search efforts continued even after all hope to find the climbers alive had passed. Some brave Pakistani climbers tried to reach the climbers on foot, but in the storm, they didn’t get very far. Helicopters flew repeatedly despite the conditions. There were also efforts to track John Snorri’s satphone. In the end, there was only sadness.

Pakistan Army pilots approach K2 BC during the search.

Snorri, Ali, and Mohr remained on the mountain. Climbers, including Sajid Sadpara, found their bodies the following summer. It was Sajid who managed to move his father’s remains from the ropes, perform the proper rituals, and bury him in the snow.

The untold story

The whole story of what happened on winter K2, from the preparations, the context, the Nepalese victory in an unspoken race, and the implications and consequences for the other summit contenders, is yet to be told.

Tribute paid on the streets of Skardu to the climbers fallen on winter K2. Photo: John Snorri’s Facebook

At the time, the five deaths partly overshadowed the historic triumph of the Nepalese team. There was the accident that took the life of Spain’s Sergi Mingote the same day that the Nepalese reached the top and the falling death of Atanas Skatov. The demise of Snorri, Ali, and Mohr, in particular, continues to have many unanswered questions, including whether these deaths could have been avoided.

We will probably never know the entire story, but hopefully, further details will surface as new footage appears and those still silent decide to speak out.

Elia Saikaly was on Winter K2 filming for John Snorri and returned the following summer with Sajid Sadpara. He may have gone further than others. “The truth no longer sought, it’s now being embodied and soon expressed,” he promises.