Chomolhari, also called Qomo Lhari, lies right on the Tibet-Bhutan border. Its north face drops down 2,700m to the Tibetan Plateau. The south side is shorter but heavily glaciated, feeding western Bhutan’s sacred river, the Paro Chhu.

For the Bhutanese and Tibetans, this 7,326m peak is the abode of the goddess Jomo Lhari, who safeguards the land, its faith, and its people. Until the 1990s, climbing was either banned or restricted because of its sacred status. Combined with brutal winds and border issues, this explains why only six known parties have attempted it in almost 90 years.

This summer, an interesting climb took place on the Chomolhari massif, which went largely unnoticed. The American Alpine Journal just reported it on November 10.

Chomolhari from Bhutan. Photo: Christopher Fynn

The first ascent

The mountain first appeared in Western mountaineering literature during the 1924 Everest reconnaissance, when Noel Odell described its north face as “a most formidable precipice of rock and ice.”

Real access, however, had to wait until the 1937 British diplomatic mission to Lhasa, headed by Basil Gould. Sir Basil John Gould (1883-1956), often known as B.J., was a prominent British diplomat and colonial administrator. He served as the Political Officer for Sikkim, Bhutan, and Tibet.

Freddie Spencer Chapman, officially the mission’s ornithologist and radio officer, managed to obtain a rare climbing permit from the Tibetan government. Chapman, accompanied only by Sherpa Pasang Dawa Lama, crossed the 5,200m south col from Tibet on May 20 and descended into Bhutan. The next day, they climbed the southeast spur in good snow conditions.

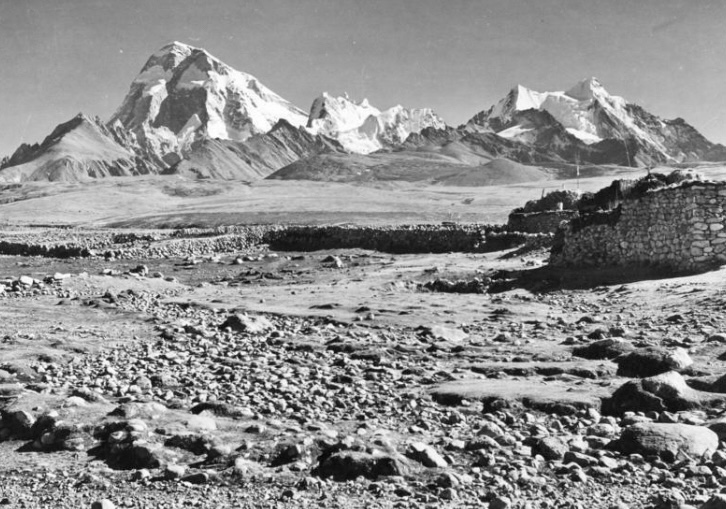

Chomolhari in 1938. Photo: Ernst Krause/Sven-Hedin-Institut für Innerasienforschung

Close call on the descent

The descent was another matter. Near the summit, while Chapman was taking a photo, Pasang slipped, carrying away Chapman. He fell 152m, but finally was able to self-arrest with his ice axe, just a few meters from a precipice.

After that, a storm hit the mountain, and the two men set up camp and waited for the storm to subside. Chapman then fell into a crevasse and spent three hours getting out on frozen ropes while Pasang held him from above. They survived the descent by eating snow mixed with barley meal.

They regained the col on May 23 and returned to Tibet. It remained the only ascent for the next 34 years.

Chomolhari from the north. Photo: Google Earth

Tragedy on the second ascent

Bhutan’s first post-war monarch, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, finally allowed climbing in 1970. An Indo-Bhutanese military expedition was organized under Lieutenant Colonel Narendra Kumar of the Indian Army, with Dorjee Lhatoo, later director of the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, as climbing leader.

On April 23, 1971, the first summit team — Prem Chand, Dorjee Lhatoo, Santosh Arora, and Sherpa Thondup — reached the top via the same southeast spur, using bamboo ladders fixed across crevasses for the lower parties. Later, in the American Alpine Journal, Lhatoo described the ritual performed before the climb: “Gold, silver, and jewels were offered to the mountain deity at base camp to ask permission for the ascent.”

Chomolhari at dawn. Photo: Christopher Fynn

The following day, a second team, consisting of Sherpa Ang Nima and Captains S.L. Kang and Dharam Pal, who were both relatively inexperienced at high altitude, left for the summit. According to the expedition report: “From base camp, they were observed through binoculars until 6,800m on the final ridge, when cloud enveloped them. They never reappeared.”

Searches began on April 26. Indian Air Force helicopters flew repeated sorties as ground parties scoured the south side and the Tibetan frontier. Only minor items, such as a telephoto lens and some food tins, were ever found.

“It is presumed that the party fell down the almost vertical north face into Tibet, a drop of over 2,400m,” Kumar recalled.

Dorjee Lhatoo later suggested that the climbers may have strayed across the border and been detained, though no evidence ever surfaced. The fate of the three men remains unknown.

The Chomolhari massif from a plane. Photo: Mario Biondo

A poorly documented ascent

After Bhutan tightened access again in the 1980s, the next confirmed ascent came from the Tibetan side. A joint Sino-Japanese expedition in 1996 or 1997 approached via the south col and climbed a variation of the southeast spur. It remains the only recorded ascent between 1971 and 2004.

In the spring of 2004, the experienced British–New Zealand couple Julie-Ann Clyma and Roger Payne attempted the striking 1,950m northwest pillar, visible from the Tibetan plateau. They established base camp at 4,500m on the west side and spent weeks waiting for a weather window.

“The wind was relentless, often exceeding 100 kilometers per hour even at camp,” wrote Payne. “Above 6,000m on the pillar, it became impossible to climb safely. Spindrift avalanches poured continuously.”

Summit by the south col-south ridge

After abandoning the pillar, Clyma and Payne crossed the south col under a full moon. On May 7, 2004, they climbed the normal route alpine-style, in a single 12-hour push from high camp. They summited in rapidly deteriorating weather and hurried down to base camp the same day.

“Chomolhari’s reputation for wind is fully deserved,” concluded Payne. “It is the dominant factor on every route.”

The northwest pillar of Chomolhari. Photo: Marko Prezelj

A Slovenian masterpiece

In the autumn of 2006, a six-member Slovenian team received one of the last-minute Chinese permits that occasionally surface for this border zone. Marko Prezelj, Boris Lorencic, Rok Blagus, Tine Cuder, Matej Kladnik, and Samo Krmelj set up base camp at 5,000m beside the sacred lake on the Tibetan side. While four members climbed a new 1,900m line up the left gully of the north face to the east ridge (TD+, sustained 80° ice), Prezelj and Lorencic spent six days forcing the direct northwest pillar that had repelled Clyma and Payne.

“We had two bivouacs of extreme discomfort,” wrote Prezelj. “At the second, under a small roof at 6,500m, the wind was so violent that sleep was impossible, and we simply waited for morning, half-frozen.”

They topped out on October 17 after climbing mixed terrain up to M6 and ice to 90° with minimal gear and no fixed ropes. The route was awarded the 2007 Piolet d’Or, the only time Chomolhari has ever received this level of international recognition.

Prezelj remarked, “On Chomolhari, the mountain decides everything. We were just allowed to pass.”

The bivouac sites of the 2006 ascent of Chomolhari’s northwest pillar. Photo: Marko Prezelj

2025: the first ascent of Chomolhari III

This year, however, an excellent expedition escaped notice in the press. In February, a Chinese expedition headed to Chomolhari. They weren’t there for the main peak, but for the unclimbed subsidiary summit, 6,706m Chomolhari III. This satellite peak sits approximately four kilometers east of the main summit, along the international border ridge.

Fu Youngpeng and Liu Yang had attempted the north spur before, but the harsh, cold wind stopped them at 6,000m. Liu returned in July 2025, this time with Song Yuancheng and He Lang.

On July 23, the trio started off, simul-climbing rapidly past the February high point. They climbed at night in order to avoid avalanche danger on the lower 700m of the spur.

According to the climbers, three distinct rock bands girdled the upper spur. The party cleared the first on day one via protectable mixed pitches. They then dug in for an uncomfortable sitting bivouac at 6,200m just below the second band.

The three Chinese climbed the second band (M4-M5) on July 25, leading to a far better night in a small cave under a boulder at 6,450m. On the summit day, they still had to solve the final crux: a steep wall of deep, unconsolidated snow that repeatedly collapsed.

Chomolhari III in the center, with the north spur facing the camera. Photo: Zhang Chengxin/American Alpine Journal

Health issues

After several failed attempts, Liu Yang found a firmer line on the right that allowed the trio to reach the summit cornice, just after midday on July 26. They downclimbed and rappelled the same line over the following two days. Liu began showing symptoms of high-altitude cerebral edema, so they started abandoning gear on tricky anchors and continuing to rappel even on easier ground.

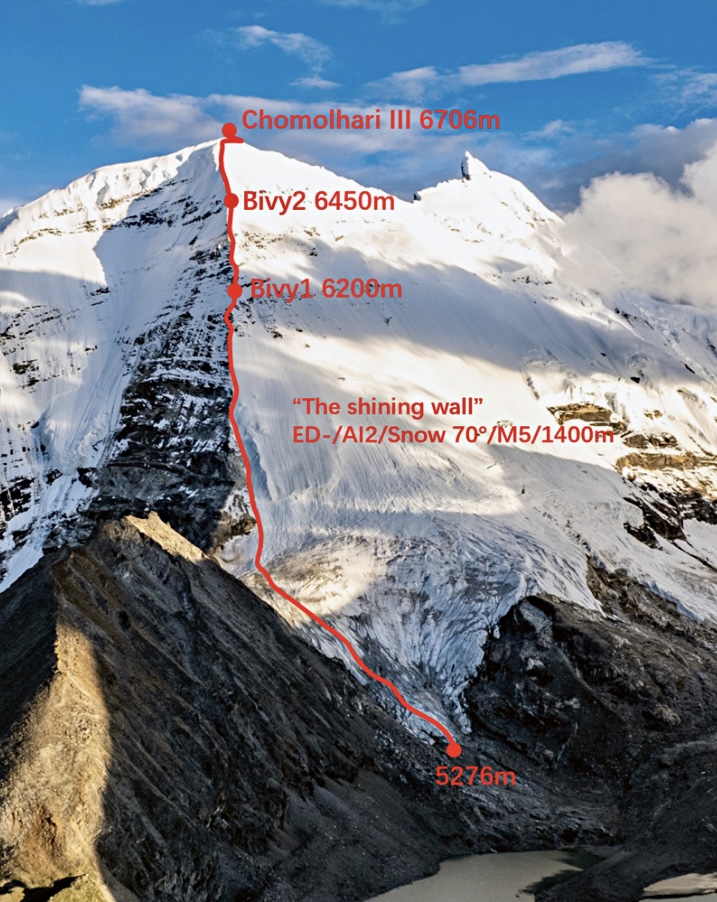

All three reached base camp on the morning of July 28, according to the American Alpine Journal, and Chomolhari III was ascended for the first time. They named their 1,400m route (graded AI2, M5, 70° snow, everything free-climbed), The Shining Wall. Note that this is not the Shining Wall of Gasherbrum IV.

The true summit of Chomolhari has remained unclimbed in recent years.

The first ascent’s route of Chomolhari III, with bivouacs marked. Photo: Chomolhari Expedition

Why so few ascents?

The reasons are straightforward and have barely changed since 1937. Bhutan doesn’t give climbing permits, and the Tibetan side is effectively closed to foreigners, since the summit ridge itself is the frontier. Then there’s the wind; almost every climbing report mentions sustained 80–120kph winds above 6,000m, even on supposedly calm days.

The 6,972m Chomolhari II, also called Tserim Kang, remains unclimbed. The slightly lower east summit, at approximately 6,922m, was reached in 2006 by the same Slovenian team that had climbed new routes on the main peak’s north side.

Altogether, the Chomolhari group is one of the most beautiful and least visited 6,000-7,000m massifs in the entire Himalaya.

Difficult mixed climbing at the start of the second rock band on the north spur of Chomolhari III. Photo: Chomolhari Expedition