Billed as the “find of the century,” Egyptologists announced in 2022 that they had found the mummy and tomb of Nefertiti. The famous 18th dynasty queen was the wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten, father of Tutankhamen and a controversial figure known for heretical religious practices.

Over the centuries, archaeologists have identified many mummified remains as candidates for Nefertiti, but without any definitive conclusion. The missing tomb and body of the legendarily beautiful queen have long been one of the greatest mysteries in Egyptology.

The announcement came from archaeologist and former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs of Egypt, Zahi Hawass, himself a somewhat controversial figure. According to his press release, Nefertiti was in Luxor’s Valley of Kings, in a tomb that contained two female mummies. When Hawass made the initial announcement, he did not reveal which mummy — KV21A or KV21B — was Nefertiti. But he promised the final news would be released that October.

Four years on, Hawass still hasn’t confirmed the identity of Nefertiti. Just what is going on with the hunt for Egypt’s missing queen?

The entrance to KV21, the tomb where two female mummies, one of which may be Nefertiti, were buried. Photo: Theban Mapping Project

How do you lose a queen?

Identifying a royal mummy is tricky business. Nearly all the tombs were looted and destroyed in ancient times, so names were removed and bodies moved around and damaged over time. Family trees are complicated and partial, with the relationships between various members further genetically obscured by the frequency of incestuous marriages.

Around the end of the 18th dynasty, many records were destroyed in the chaos and religious upheaval of the Amarna period. Nefertiti has been especially difficult to pin down. Egyptologists aren’t completely certain who her parents were, and also can’t confirm which children of Akhenaten are hers.

Her year of death isn’t known for sure, either. If she died before her husband, she likely would be buried in his city of Amarna. Many historians now believe she outlived him and ruled on her own or as the young Tutankhamun’s regent. If so, she would be buried in the Valley of Kings, the Gurob necropolis by Fatyum, Thebes, or even her home city of Akhmim. Many of the likeliest tombs, however, are in the Valley of Kings.

Akhenaten, left, husband of Nefertiti, right, rejected the Egyptian religion. Instead, he worshipped the sun disc, Aten. He moved his capital to the middle of the desert and built his own city, Amarna. This made a lot of people very angry and is widely regarded to have been a bad move. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A long line of false Nefertitis

Hawass, it turns out, announces a new finding of Nefertiti on a fairly regular basis. And he’s not the only prominent Egyptologist to make Nefertiti claims which haven’t been proven.

Discovered in 1898, KV35 was originally the tomb of Amenhotep II. Later Egyptians used it as a mummy cache, storing old royals in there like one would loose rubber bands in a kitchen junk drawer. Two of these mummies, dubbed the Elder Lady and Younger Lady, were found tucked away in a side chamber alongside the body of a young prince.

The Elder Lady was cited as a potential Nefertiti until 1976, when comparison with a lock of hair from the tomb of Tutankhamen showed she was actually Queen Tiye, mother of Akhenaten. In 2003, author Joann Fletcher created a minor media storm by announcing that the Younger Lady was, in fact, the lost Nefertiti. There was a Discovery Channel special and everything.

Hawass himself was strongly against the theory and organized a DNA test to disprove it. When the test results came in, they showed that the Younger Lady was the mother of Tutankhamen, the daughter of Queen Tiye, and the full sister of Tutankhamen’s father, Akhenaten. We’re fairly certain that Nefertiti was not the daughter of royalty. So the Younger Lady must be one of Akhenaten’s minor wife-sisters.

Another would-be Nefertiti media circus came in 2015. University of Arizona archaeologist Nicholas Reeves announced that he’d found a secret chamber behind a wall of King Tut’s tomb, and that Nefertiti was likely behind the wall. There wasn’t, and she isn’t.

Queen Tiye, the young prince, and the mother of Tutankhamun in KV35. Photo: Egyptian Museum, Cairo

So, who’s the latest Nefertiti?

KV21A and B are not new finds. The tomb has been discovered and rediscovered several times since 1817. In fact, Hawass conducted DNA analysis on the two women the same year he analyzed the KV35 remains. But the remains in KV21 are badly damaged. As a result, Hawass and his team were unable to construct full, definitive profiles.

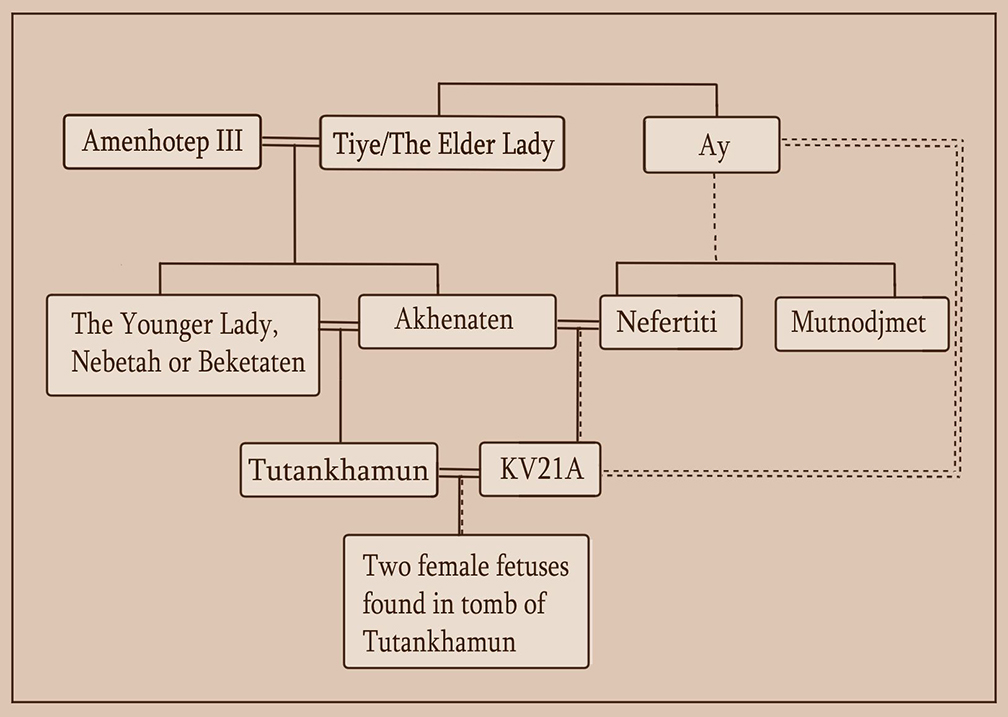

Based on the limited results, however, it seems that KV21A may have been the mother of the two fetuses buried with Tutankhamen. Testing has confirmed that he is their father, meaning if KV21A is their mother, she is one of his wives. As I mentioned earlier, Egyptian family trees are complex and often confusing. The diagram below might help a little.

A simplified family tree of the late 18th dynasty royal line, centering on the Amarna period. KV21B is not included because there is not enough genetic evidence to know where she should be placed.

There are alternate readings of the DNA evidence, but either way, she probably isn’t Nefertiti. For one thing, she seems to have died in her early twenties, making her too young.

So if a KV21 mummy is Nefertiti, it’s B, whose estimated age (45) aligns with Nefertiti’s. Analysis of this mummy couldn’t go any further than to say she fit somewhere into the 18th dynasty royal line, and may be the mother of KV21A. If these shaky identifications are correct, this mummy could be Nefertiti. But she could just as likely be her sister Mutnodjmet, or another wife of Akhenaten.

In late 2023, Hawass told The Sun that he planned to announce the identity of Nefertiti within four months. Then, in a December 2024 interview, Hawass said he was pretty sure Nefertiti would be found in 2025. Well, better luck next year.