In early July of 1908, Luigi Pernier was heading an archaeological mission to Crete. One evening, the Italian was writing a letter to his superiors when he was interrupted by the arrival of Zacharias Eliakis, who supervised the dig that afternoon. Eliakis had a strange object with him.

It was a clay disk, the size of a dinner plate, and still covered in dirt. Pernier examined the object. There appeared to be writing in an unknown language, carved into the disk. Thrilled with the discovery, Pernier added a postscript to his letter, describing the disk. He signed off saying that this object might be “one of the most important monuments of early Cretan writing.”

Over a hundred years later, the object which came to be called the Phaistos Disk remains unique and completely untranslated.

A group from the Italian school of archaeology in Crete in 1899. Zacharias Eliakis is second from the right. Photo: Archives of the Italian School of Archaeology

A singular object

The disk was uncovered in the Phaistos acropolis, an ancient Minoan site near the southern coast of Crete. A massive palace surrounded the city of Phaistos. The Minoan people had been living there since 3,600 BCE. Excavation had been ongoing for nearly a decade before Eliakis uncovered the disk.

He found it in a basement on the north end of the palace, in an area dating to around 1800 BCE, the Middle Minoan period. With it was a tablet with writing in Linear A, a still undeciphered ancient Aegean script, and pottery from that Middle Minoan period.

The disk itself was made of very fine clay, about 2 centimeters thick and 16 centimeters across. It’s not perfectly circular, as it was made by hand rather than with a mold. Its creator stamped 242 individual figures into the wet clay, laying down the sigils in concentric circles, separated by lines, on both sides of the disk. Then it was fired at high heat, preserving it. The use of stamps makes this disk the first known use of movable type.

The writing was unlike anything else archaeologists had found in Crete. The Middle Minoan people had both the Linear A script and a slightly earlier one called the Cretan Hieroglyphic. The Phaistos Disk’s carefully stamped people, plants, animals, and objects represent a third, seemingly unrelated writing system, in use at the same time as the other two. That is, quite frankly, too many writing systems for one island.

Part of the sprawling Phaistos complex, where successive generations of Minoans built and rebuilt their palaces, and spent their time coming up with new writing systems. Photo: Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

Early excitement, first attempts

Classicists rushed to be the first to interpret the new discovery. Dr. Arthur Evans was the first notable figure to step forward. Evans had led excavations at the Minoan palace of Knossos, even coining the name “Minoan,” after the legendary Cretan king Minos. He’d also worked with Linear A and B, discovering that they were two different systems and assigning them the names we still use.

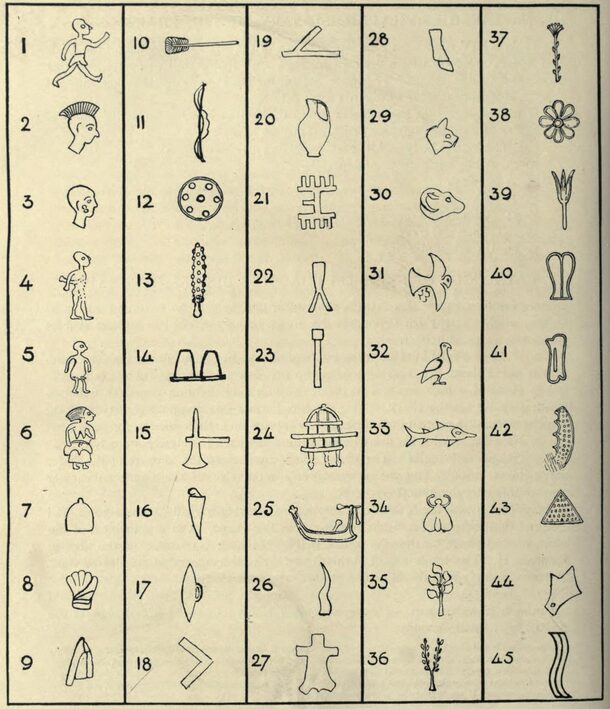

Evans argued that the disk wasn’t even Cretan, but had come from somewhere in Asia Minor. He numbered the unique symbols 1-45 and categorized them.

He disagreed with Pernier on number seven, arguing that it was not a hat but a breast, and therefore indicated a female divinity. Evans was a prominent figure in the “Great Goddess” theory, which posited that a single matriarchal deity had been worshiped across Eurasia since prehistory. This is now largely debunked, and I really can’t get into it, so let’s move on.

He also linked number 29, the cat, to this goddess. The two symbols appeared together several times, and both appeared with 24, which he believed was a temple. The fact that it did not resemble Minoan temples was, he argued, an indication of the symbols’ non-Cretan origin.

Evans argued that the Linear A tablet found with the disk proved that in Crete, hieroglyphic systems were out of date by the time of the Phaistos disk. But in Anatolia, with whom the Minoans were in contact, hieroglyphs were still in use. That was as far as he got in terms of deciphering it, though.

Evans’ numbering of the Phaistos disk symbols. Photo: from Evans’ 1909 book, ‘Scripta Minoa’

Continuing attempts, continuing failure

How do you read something written in an unknown language, with unknown letters, when you don’t even know what direction or order the symbols are read in or what many of them represent? The seeming impossibility of the task only attracted more challengers.

Stanford doctor of philology George Hempl examined the disk and made early progress, noting with Sherlock Holmesian panache that the way pressure was applied to the stamps showed they had been made from the outward side in, and right to left, not the reverse as Evans suggested. The number of unique sigils, furthermore, meant that each one represented a syllable, not a word or a single sound.

Hempl’s proposed solution hinged on the text being written in Greek. His technique was a more sophisticated application of something called Frequency Analysis. This matches the frequency of a symbol appearing against how often it appears in the language on average. Hempl generated a religious text, from which he spun an involved story of pillaging Cretan privateers, an Ionian priestess, and a cattle-based cult. This theory is not accepted by modern scholars.

As the decades wore on, classicists, philologists, cryptographers, and people with no qualifications whatever attempted to solve the mystery of the disk. It was interpreted as a receipt, calendar, game board, hymn, land title, work of fiction, mathematical treatise, and whatever Hempl thought was happening. The language was variously assumed to be Ionic Greek, Attic Greek, Luwian, Hittite, Egyptian, Basque, Dravidian, Semitic, Sumerian, and more.

As the years went on, and the gibberish translations piled up, some scholars began to question if the Phaistos Disk was real at all. Wasn’t it suspicious that these symbols hadn’t turned up anywhere else in Crete?

The confounding disk. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Rings, combs, and bowls

Then, the symbols started turning up elsewhere in Crete.

In 1934, Greek archaeologist Spiridon Marinatos found the Arkalochori Axe in a cave in central-eastern Crete. This axe has 15 pictographic signs, several of which appear to match those of the Phaistos disk. In particular, symbol 2, the head with a plumed helmet or hair, appears several times on both artifacts.

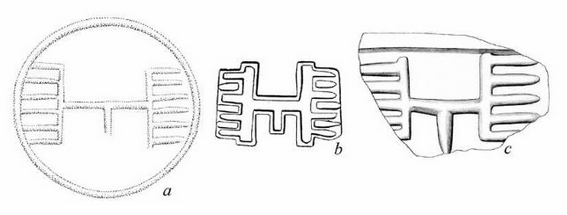

In 1965, a team led by Doro Levi, another Italian archaeologist, was excavating the ruins of a building in Phaistos. Among the ruins was a collection of pottery and scraps. On an otherwise unassuming bowl was stamped number 21, the comb. The same comb symbol turns up again, stamped on a broken tablet in Phaistos, also found long after the disk.

The ‘comb’ symbol on the bowl (a), the Phaistos Disk (b), and Sealing CMS II.5 (c). Photo: CMS Heidelberg

Later artifacts also provide parallels to the spiral writing arrangement. Near the Minoan site at Knossos is a necropolis centered around the Mavro Spelio cave. During the 1920s, Arthur Evans found a gold signet ring there while excavating the tombs. The writing was arranged in a spiral pattern, just like on the disk. All of the artifacts seem to date from the Middle Minoan period.

The ‘Mavrospilio ring’ with Linear A inscriptions, found in 1926. Photo: Collections of the French School of Athens

Phaistos fraud?

In 2008, the speculation that had been simmering for a century was reignited. Jerome Eisenberg was an antiquities dealer who dedicated himself to sniffing out fakes and standing up against illegal and unethical antique importation. He also edited his own archaeology magazine, Minerva. For the centennial of Luigi Pernier’s discovery, Eisenberg published an article in Minerva arguing that the disk was a hoax, perpetrated by a jealous Pernier.

Eisenberg’s theory went as follows: Pernier, seeing Evans’ success in nearby Knossos, and the relative lack of finds, especially writing, from Phaistos, decided to craft an untranslatable text which would boost his reputation and impress Evans and his own mentor, Federico Halbherr. Familiar with Italian artifacts, Pernier based his creation on the Etruscan Magliano Disk. Found in 1882, the Magliano Disk was a lead plate with a spiral of writing on both sides.

Defenders of the disk pointed to nearby, contemporary parallels as evidence that it was genuine. But Eisenberg interpreted these as sources of inspiration for Pernier’s forgery. He pointed to several signs that were similar to symbols in Linear A and B, as well as other “stamped” symbols in Minoan artifacts.

At the same time, Eisenberg argued that the uniqueness of the disk was evidence of forgery. There were no other flat clay disks in the Bronze Age, nor “other hieroglyphic script of this type.”

His article is detailed and lengthy, breaking down the suspicious circumstances of the find (which occurred during a late inspection) and the linguistic issues with the script. For instance, he argued that there were too many unique signs and too few repetitions to be real writing.

The Magliano Disk. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Why no thermoluminescence?

Eisenberg’s claims inspired new appraisals of the disk. Many called for thermoluminescence analysis, a precise dating technique that involves heating a small sample and measuring the amount of radiation it absorbs. This test would give its proper age and settle the authenticity question pretty definitively.

The Archaeological Museum in Heraklion has declined to do so. Partly, they are resistant to anything that would damage the disk, even slightly. But also, they have nothing to gain and everything to lose from a test. But even without the definitive proof, many scholars are willing to argue for the disk’s authenticity.

Pavol Hnila, a researcher at the University of Berlin, responded to Eisenberg in 2009. Analyzing Pernier’s personal letters, Hnila argued that Pernier had not behaved like a jealous forger. He was open and sincere about the potentially suspicious way the disk was found. If he had wanted to, his position would have allowed him to arrange a much less questionable discovery. Pernier himself raised the similarity of his finding to the Magliano disk.

As for the writing, Hnila and others pointed out that the parallels to other languages could be due to cultural interaction in Minoan times. It’s normal for writing systems developed in the same region and era to borrow symbols from one another. Some of the best proof, however, comes from a recent investigation into what else has turned up at the Phaistos site.

Similar artifacts to the Phaistos Disk

Along with the disk and the Linear A tablet, the basement ruin was filled with pottery. During the Middle Minoan period, when the disk was made, Minoans were making a particular type of fine ware decorated with stamps. These stamp marks were largely ornamental, with geometric or floral designs, but some are clearly representational.

In fact, a number of those vessels’ designs have symbols that match those on the Phaistos Disk.

The Impressed Fine Ware sherds, then the symbol outlined, with the equivalent Phaistos Disk symbol on the far right. Photo: Alessandro Sanavia via Giorgia Baldacci et al

So the Phaistos disk is not the only stamped, fired clay item from this era. It’s true that so far, it remains unique. But if it were a special or ceremonial object, it would certainly be more cleanly made than the ordinary bric-a-brac of Minoan life. Today, most scholars think that the disk is likely genuine.

But even if the disk is real, translating it, without other examples of this script, is nearly impossible. That doesn’t stop people from trying. John Chadwick, the scholar who translated Linear B, was so bombarded with attempts he had to put out a request that people stop sending him their Phaistos disk solutions. Decades on, the field is even more crowded.

Multiple papers have come out in recent years, bringing the weight of computing power to bear on the problem. So far, they have not triumphed.