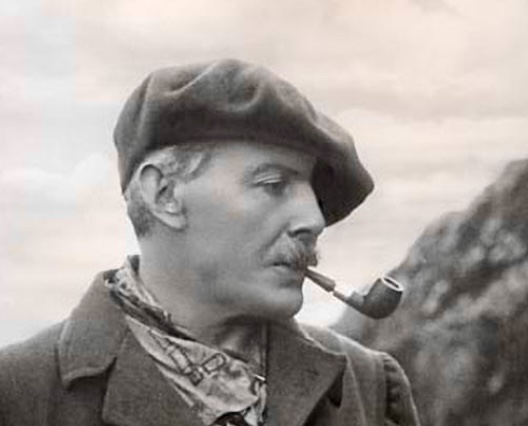

Geoffrey Winthrop Young (1876-1958), British climber, poet, and author of several books, was one of the most important and influential figures in the history of British mountaineering. His significance was not only due to his notable climbs. He shaped the sport technically, ethically, and culturally.

Young was born into a wealthy, intellectual, and climbing family. His father, Sir George Young, was a baronet and classical scholar who had pioneered early Alpine routes. When Sir George’s brother died in a climbing accident on Mont Blanc in 1865, he decided to quit climbing. He even banned any mention of climbing in the family home. But sons and daughters often defy their father’s taboos, and when Geoffrey Winthrop Young was a young man, he discovered the beauty of climbing.

At the age of 21, Young ascended Mont Blanc with a guide. After that, he fell in love with mountaineering. He started climbing in Britain and Wales during the school holidays while he worked as a teacher. However, at that time, the ethic of going without a guide was already emerging. In 1904, Young already held the opinion that hiring guides was something outdated for skilled amateurs.

The Formosa Place, built in the 1780s by Admiral Sir George Young. Photo: jlpmemorystore.org.uk

Ascents in the Alps

From 1905 to 1914, Young led a small, elite circle that systematically climbed hard lines in the Alps without guides, often in lightweight style and in bad weather. One of his partners was Josef Knubel, one of the era’s top Zermatt guides, whom Young later called his ideal companion.

Together and with others like Siegfried Herford, they carried out an astonishing number of notable ascents in the Alps, including:

- the Southeast Face of the Weisshorn and the Furggen Ridge of the Matterhorn in 1905

- the first ascent of the South Ridge of Täschhorn

- new routes on the Weisshorn and Dom in 1906

- the Midi-Plan traverse in less than 15 hours

- the Southeast Ridge of Nesthorn

- new routes on the Rimpfischhorn and Zinal Rothorn in 1907

- the ascent of the Mer de Glace face of the Aiguille du Grepon in 1908

- the Northeast Face of the Charmoz in 1909

- the first ascent of the Brouillard Ridge of Mont Blanc with H.O. Jones and George Mallory

- the first complete traverse of the West Ridge of the Grandes Jorasses

- the first guideless traverse of the Frontier Ridge of Mont Maudit in 1911

In 1913-14, he ascended the Zmutt Ridge of the Matterhorn and the West Ridge of the Gspaltenhorn with Herford. This was Young’s last great pre-war climb.

Transformative

These weren’t always the hardest ascents of the era, because climbers like Hans Dulfer and Paul Preuss were already pushing free-climbing to new levels in the Kaiser and the Dolomites.

But in British alpinism, Young’s ascents were transformative. They proved amateurs could match professionals, emphasizing balance, trust, and minimal gear over brute force. And that was the point.

Furggen Ridge, Matterhorn. Photo: Summitpost

From around 1907, Young organized legendary Easter and Christmas meets at the Gorphwysfa Hotel (later called the Pen-y-Pass Youth Hostel) in Snowdonia. Up to 60 climbers — men, women, and even children — converged for two weeks of cragging on sites like Clogwyn du’r Arddu and Idwal Slabs. Evenings of lectures, rope practice, and debate followed these days of climbing.

These gatherings were the beginning of a climbing school for the next generation. Women climbed on equal terms, a rarity then, and the atmosphere fostered an “almost ideal social fabric.”

Every key British climber of the interwar years went to those meetings, including Mallory, Herford, John Percy Farrar, and Oscar Eckenstein. Young taught balance techniques, modern belaying, and the moral weight of leadership.

The Alpine Club archives highlight these get-togethers as the beginning of British rock ethics, shifting from “engineer’s climbing” (top roping) to free, partnership-based ascents.

Young also pioneered new British routes on Northumberland crags, the Lake District, and on Welsh slate.

The YHA Snowdon Pen-y-Pass. Photo: gonorthwales.co.uk

Mallory mentor

George Leigh Mallory met Young at the 1909 Pen-y-Pass meeting. The 33-year-old Young realized that the young Mallory (then 23) was a talented climber and invited him to the Alps.

From 1911–1914, Mallory roped up almost exclusively with Young, and they climbed together the Brouillard Ridge, Mont Maudit Frontier, the Grepon North Ridge, and more. Young imparted his guideless ethics, balance moves, and alpine minimalism. All these influenced Mallory’s later style.

Their bond was fraternal. Young was the best man at Mallory’s 1914 wedding. As Alpine Club records note, Young was Mallory’s “principal guide” in his formative years. Without him, the Everest icon might have stayed earthbound.

Injured in WWI

In 1914, World War I broke out. Working as a correspondent for the Daily News, Young crossed to Belgium after Mallory’s wedding. As a conscientious objector, he joined the Friends’ Ambulance Unit in Flanders and then commanded the First British Ambulance Unit for Italy in 1916. On the brutal Isonzo Front, he drove ambulances under fire. There were no fatalities under his command, and he saved thousands, earning the Belgian Order of Leopold and Italian Silver Medal for Valour, as well as British decorations.

On August 31, 1917, during the assault on Monte San Gabriele, shrapnel shredded his left leg above the knee, which had to be amputated. It seemed that his climbing career was over. But Young didn’t give up. He designed an aluminum prosthetic leg and tested it on Tryfan in 1919. As Wayne Willoughby reported in the American Alpine Journal, Young wrote to Mallory about his plans to continue climbing: ”Now I shall have the immense stimulus of a new start, with every little inch of progress a joy instead of commonplace. I count on my great-hearts, like you, to share in the fun of that game with me.”

Geoffrey Winthrop Young climbing in North Wales with his prosthetic leg. Photo: Richard Hargreaves Collection via everywhereandnowhere.le.ac.uk

‘I keep the dreams I won’

From then until 1935, Young climbed routes like the South Ridge of the Täschhorn, the Matterhorn, the Petits Charmoz, Dent du Requin, Grepon, Zinal Rothorn, and Monte Rosa, which companion Claude Elliott called “the greatest physical feat” he had ever witnessed.

We can see his impressive resilience in his beautiful post-amputation poem of 1917, entitled I Hold the Heights:

I have not lost the magic of long days;

I live them, dream them still.

Still I am a master of the starry ways,

And freeman of the hill;

Shattered my glass, ere half the sands had run –

I hold the heights I won.

Mine still the hope that haileth me from each height

Mine the unresting flame.

With dreams I charmed each doing to delight;

I charm my rest the same.

Severed my skein, ere half the strands were spun –

I keep the dreams I won.

What if I live no more those kingly days?

Their night sleeps with me still.

I dream my heart upon the starry ways;

My heart rests in the hill.

I may not grudge the little left undone;

I hold the heights, I keep the dreams I won.

Writes ‘Mountain Craft’

In 1920, Young published Mountain Craft, which remains one of the most important manuals in mountaineering history. It focuses on different topics: technical skills, route-finding, mountain judgment, reading terrain and weather, history and ethics, training and leadership, and first aid and rescue techniques. In fact, the book contains one of the earliest systematic approaches to mountain rescue in print.

Mountain Craft remained the standard reference for serious mountaineers for decades. He also wrote: The Roof-Climber’s Guide to Trinity (1899), Wall and Roof Climbing (1905), Freedom — Poems (1914), From the Trenches: Louvain to the Aisne, the First Record of an Eye-Witness (1914), On High Hills: Memories of the Alps (1927), Collected Poems (1936), Mountains with a Difference (1951), The Grace of Forgetting (1953), and Snowdon Biography with Sutton & Noyce (1957).

”For the youngest, as for readers of all ages, it is a blessing that his books will always be there,” wrote David Allan Robertson Jr. in the American Alpine Journal in his remembrance piece on Young.

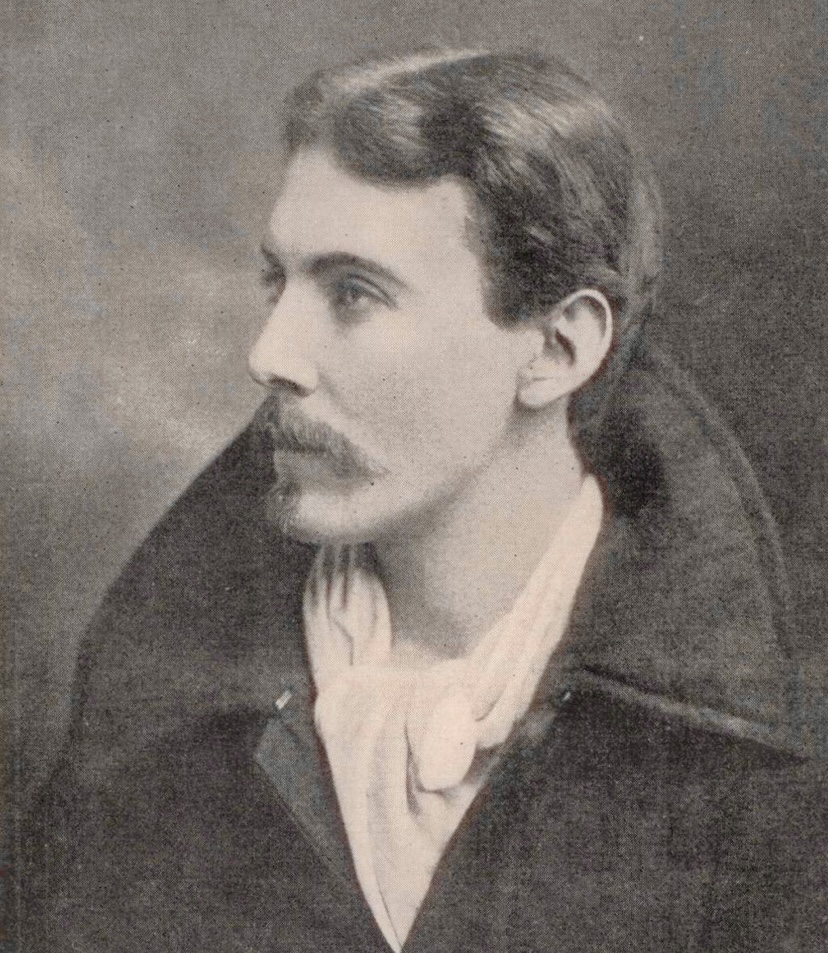

Geoffrey Winthrop Young in 1898. Photo: Wikipedia

Young died on September 8, 1958, at age 81.

When historians list the handful of people who changed mountaineering, Young’s name is always there. Few have touched the sport at so many decisive points. As the American Alpine Journal noted in its 1959 obituary, Young exemplified melding mind and body, graciously and gallantly, into full play. Young stands in much the same relationship to his era as Edward Whymper was to the Golden Age or Albert Mummery to the Silver Age of alpinism.

You can read Mountain Craft here.