For over fifty years, a prehistoric rhinoceros mass grave has baffled paleontologists. Over one hundred rhino skeletons were found in the same spot, having all died together 12 million years ago. Now, a new study has revealed that this mass of animals, which died together, also lived together in one huge herd. How do we know? Their teeth.

Once hidden just under the surface, now a barn protects the rhino grave from the elements. Photo: University of Nebraska State Museum

Rhinos buried in ash

Located about 160 km from Sioux City, Iowa, the Ashfall Fossil Beds were created by the Yellowstone volcanic eruption 11.9 million years ago. When the volcano blew, a dense blanket of ash covered the entire region. Smaller animals died almost instantly, suffocating on the abrasive ash.

For larger, hardier creatures like the Teleoceras major, the barrel-bellied rhino, it was slower. Volcanic ash, on a microscopic level, is actually quite sharp, like tiny shards of glass. As it filled their lungs, animals slowly sickened and died. They came to the watering hole, seeking some relief in the cool water. There they died, and the wind swept more ash on top of them. What had killed them also preserved them perfectly.

In 1971, Michael and Jane Voorhies were walking down gullies in Northwestern Nebraska. Michael was a University of Nebraska State Museum paleontologist who hoped that erosion by nearby Verdigre Creek had revealed fossils.

It had. Emerging from the side of a gully was a flash of white bone, suspended in ash. Michael had found the skull of a baby rhinoceros. Excitingly, the skull was still connected to the neck, and the neck to the body.

Six years later, Dr. Voorhies came back with a crew from the University. The site is now part of a national park and is still an active dig site. The animals are suspended in layers showing their order of death: Small birds at the bottom, which succumbed first, then horses and camels, and rhinos last. There are over 20 species in total, and hundreds of skeletons, most of them rhinos.

This bone map shows only a fraction of the remains found in Ashfall. Photo: University of Nebraska State Museum

Enamel revelations

However, paleontologists weren’t sure at first why the rhinos had all come together in such huge numbers. Were these separate individuals and small herds, all fleeing to the same hole? Or could they really be part of a single massive herd? Researchers at the University of Cincinnati set out to answer the question.

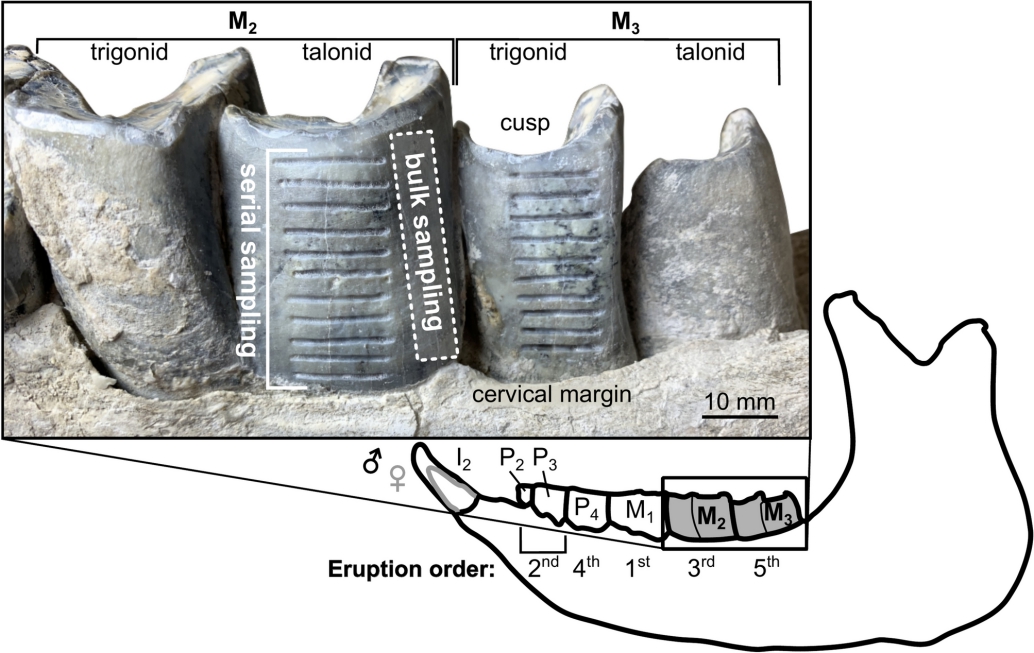

They took samples from the tooth enamel of more than a dozen individuals. Then they analyzed the isotope ratios present in the enamel. Atoms of the same element can have different numbers of neutrons, resulting in different “species” of a given element. Isotope analysis measures the relative amounts of these different species of element. Because different isotopes occur in different environments, and therefore different foods, isotope analysis tells scientists what (and therefore where) an animal was eating.

Using this analysis method, they were able to examine where and why the individuals were moving. Had they traveled a long distance to avoid destruction? Did they migrate seasonally, or leave for new territory upon reaching adulthood?

As it turns out, the answers to those questions are no, no, and no. All the individuals they sampled had been eating the same local food for their whole lives. Comparing their isotopic signatures to another local animal, a sabre-toothed deer, revealed a more aquatic diet. If T. Major was semi-aquatic, like modern rhinos, this would have restricted its movement, explaining the lack of migration.

The hundred-strong rhino group at Ashfall hadn’t come together by chance, all fleeing the same disaster. They were one large herd, who had lived together and died together.

Researchers took careful samples from the large, powerful teeth shown above. Photo: Ward et al

A stroll through prehistoric Nebraska

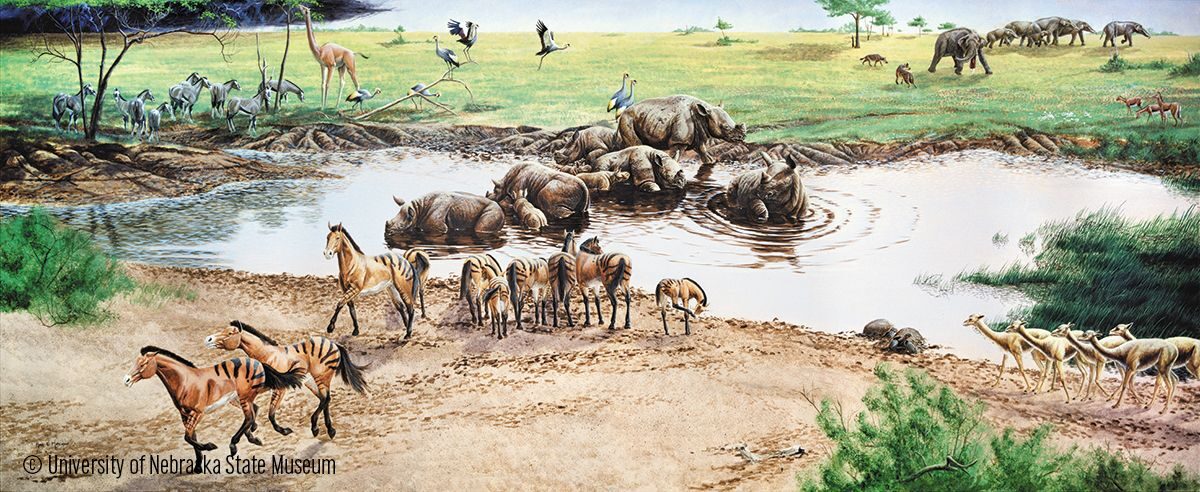

Before the eruption, Mesozoic Nebraska was a vast savannah, crisscrossed with streams and watering holes. Grazing animals fed on the open grasslands. The long-necked Aepycamelus, a giant extinct camel, grazed on the treetops, while small three-toed horses like Pseudhipparion gratum and Neohipparion affine munched on the grass beneath them.

The smaller grazing animals and the young of their larger cousins had a number of canine enemies to watch out for. The deadliest of them was Epicyon, the massive “bone-crushing dog” that weighed up to 170 kilograms.

Moving placidly along riparian corridors were great masses of barrel-shaped T. Major. Growing up to four meters long, they were low to the ground, built more like the modern hippopotamus. In massive herds of dozens of these fleshy, tusked tanks, they enjoyed their muddy wallows, unconcerned by the bone-crushing dogs.

The volcanic eruption was not the end of T. Major. The rhino species persisted for another seven million years, until climate change froze its wet, temperate grasslands.