There are explorers who plumb great depths: Bob Ballard, Jacques Cousteau, or even James Cameron. Then there are adventurers who take to the skies: Chuck Yeager, Neil Armstrong, and Amelia Earhart, just to name a few. But explorers equally at home soaring through the clouds and drifting through the lightless depths?

Those are a rare breed.

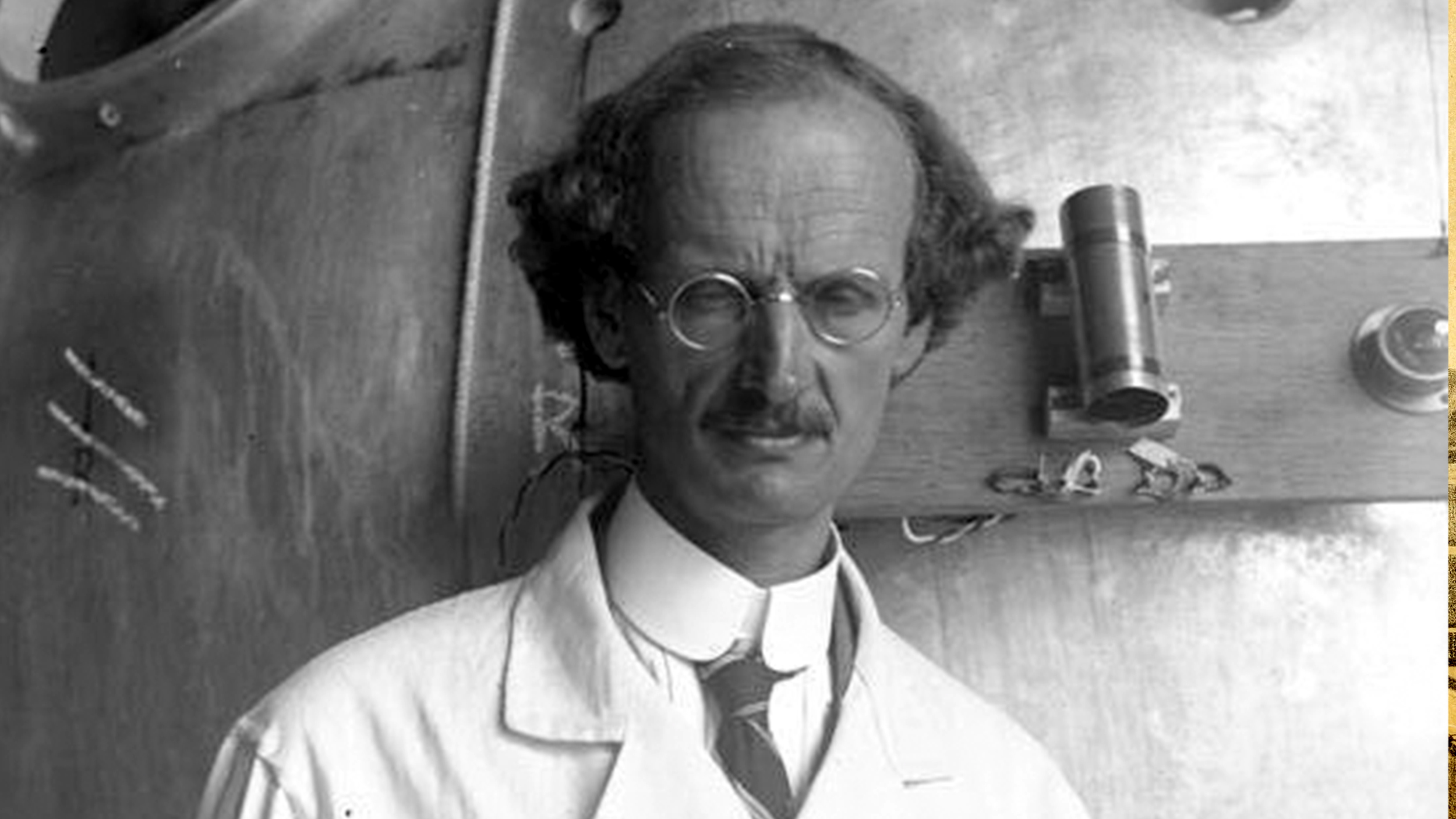

Auguste Piccard, with his gangly frame, high forehead, and bespectacled gaze, doesn’t fit the classic mold of a hardy explorer capable of withstanding some of the most extreme conditions on Earth. But it’s what that forehead contained that allowed him to construct devices that would take him to the stratosphere and the ocean floor.

Along the way, he raised a family of explorers, was immortalized in popular culture, and laid the foundations for modern space and deep sea exploration.

It all started, as so many good things do, in Switzerland.

A genius from the start

Auguste Antoine Piccard was born on Jan. 28, 1884, in Basel, Switzerland. He shared his birth with his twin brother Jean Felix Piccard, who also became a pioneering scientist and explorer in his own right.

It was a fascinating year for a brilliant mind to enter the world. Consider this — when Piccard was born, the Wright brothers were still 19 years away from Kitty Hawk, and the transistor was 63 years from being invented. It was a world of horse-drawn carriages and steam-powered ships. By the time Piccard died in 1962, the first moon landing was cresting time’s horizon.

The Swiss scientist is responsible for many of the exploration advances we take for granted today. But first, he had to train that mind.

Unlike his more famous contemporary, Albert Einstein, Piccard excelled at school. A head perpetually in the clouds was destined to reach them, and an education at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology helped considerably. By 38, he had settled into a comfortable physics professorship at the Free University of Brussels.

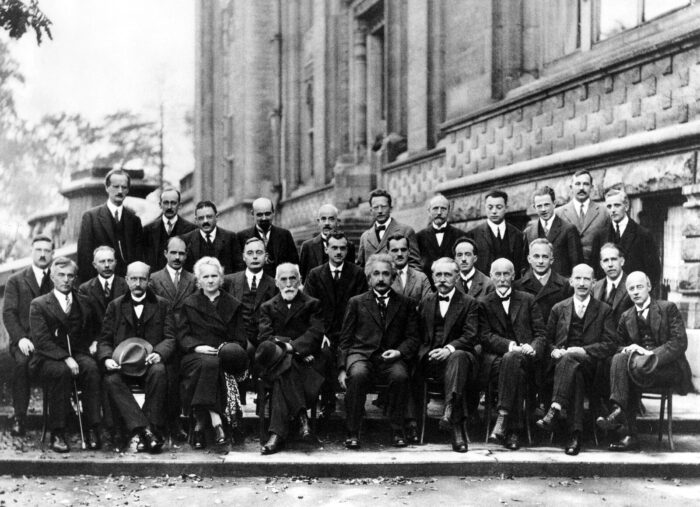

Recognized by his peers as an unparalleled thinker, Piccard was a member of the Solvay Conference multiple times in the 1920s and 30s. The Conference was a sort of think tank dedicated to solving the most pressing scientific problems of the day. The 1927 Conference, for instance, focused on electrons, photons, and quantum theory.

A photo from the 1927 Solvay Conference. Piccard is at the far left of the top row, towering over everyone else. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Alongside Piccard, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, and Marie Curie also attended. Of the 29 scientists, 17 would become Nobel Prize winners. That’s a fertile breeding ground for innovation, and it is no surprise that by 1930, Piccard was ready for innovation of his own.

Head in the clouds

Piccard was on friendly terms with Einstein because of their shared education at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and mutual experiences at the Solvay Conference. At the time, Einstein was working on theoretical cosmic ray research and Piccard had a bug in his ear to collect some hard data in support of his friend’s theories.

To do so, someone needed to ascend to the stratosphere, a never-before-reached layer of Earth’s atmosphere beginning some 10km above ground. That’s roughly the cruising altitude of a modern-day commercial airliner and 2,000m higher than Everest (which was still 23 years from a successful summit).

So, how could you keep a human alive up there? Piccard hit upon the idea of a spherical, aluminum, pressurized capsule attached to a balloon. With money from the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research, he built the thing. By 1931 it was ready to ascend.

Perhaps few of his colleagues expected the bookish, 2m-tall scientist to wedge himself into the capsule and pilot the thing himself. After all, here was a man who never went anywhere without a slide rule, a man who wore two wristwatches.

But inside that lanky frame beat the heart of a lion. Piccard had served in the Swiss military’s balloon corps and had already made a high-altitude balloon flight to test another of Einstein’s theories.

Into thin air

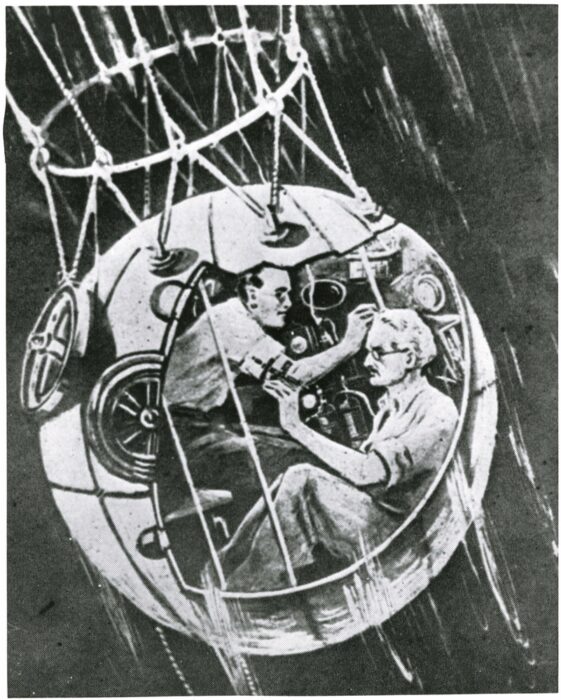

The device, which Piccard called “The Gondola”, took off from Augsburg, Germany, on May 27, 1931. It was lifted into the sky by a hydrogen balloon. German authorities, convinced the men were doomed, insisted they wear helmets. Piccard and his co-pilot Paul Kipfer hadn’t brought any, so they cheekily plopped baskets atop their heads and closed the hatch.

Piccard (right) and Kipfer (left) modeling their state-of-the-art safety equipment.

Some 16 hours later, overdue to return, they were given up for dead.

But despite the best efforts of the liminal space between the welcoming earth and the hungry sky, they were still very much alive.

The problems had started almost immediately. Rising quickly enough to make even the implacable Piccard a bit nervous, the two men tried to release a little hydrogen gas from their balloon, only to discover the release valve was frozen shut. That would make descent tricky, to say the least. But that was a problem for another time.

Of more immediate concern were conditions inside the sphere. Piccard had thought ahead and painted The Gondola half white and half black, then attached a motor to rotate the sphere to reflect or absorb solar radiation as the internal temperature dictated. But the motor burned out with the black side facing the sun. Piccard and Kipfer quickly faced temperatures over 37°C.

This photo showcases the half-white, half-black temperature regulating design on The Gondola. Unfortunately, it didn’t work. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Soon enough, they were licking their condensed perspiration off the walls.

Then, The Gondolla’s shell sprang a leak.

As a high-pitched whistling filled the cramped space, Piccard scrambled for a makeshift patch, eventually settling on a petroleum jelly-soaked scrap of cloth. Soon after that emergency had been addressed, the barometer shattered, spilling liquid mercury all over the compartment.

An illustration showing Piccard and Kipfer in The Gondola as they ascend to the stratosphere. A tight fit when one of you is 2m tall. Photo: National Air and Space Museum

The two men’s attempts to clean up the liquid were stymied by its famously slippery properties. Finally, they attached a hose to an exterior valve and used the near-vacuum of the stratosphere to suck the liquid metal out.

After seventeen hours of this sort of thing — and eventually reaching a record-shattering height of over 15,000m — the cold finally contracted the hydrogen in the balloon and The Gondola had a bumpy but successful landing on an Austrian glacier.

As the two men were hiking toward the nearest town, they bumped into the search party that had been sent to collect their corpses.

Under the waves

What with all the survival Piccard and Kipfer were doing during their flight, there wasn’t a lot of time for science. Einstein’s theories about cosmic radiation would have to wait to be conclusively proven. But the two men managed to collect enough promising data to encourage further high-altitude balloon flights, and the world was in awe of the record-breaking ascent.

But Piccard wasn’t one to rest on his laurels.

Taking what he learned, he turned his attention to the unexplored world beneath the waves.

With the sphere again serving as a starting point, Piccard designed and built the FNRS-2. World War II delayed construction, but by 1948, it was ready for unmanned dives.

This illustration was created while Piccard was still conceptualizing his submersible design. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The craft was a steel capsule suspended beneath a float of low-density liquid and weighted down by tons of iron. When the FNRS-2 reached its desired depth (it was capable of withstanding pressure of up to 6,700 psi, far more than any other submersible of its day), it could release the iron and float gently toward the surface. While in Piccard’s hands, the FNRS-2 never made a manned voyage. But it was a useful tool to demonstrate just how deep Picard’s mind might one day take his body.

By this point, Piccard’s son Jacques had joined him in his research. After giving the French Navy the FNRS-2 in 1950, Piccard and his son designed and built a second submersible. In 1953, they manned it to a depth of 3,150m — another record.

In 1954, that record was smashed by a Frenchman descending to 4,176m using a slightly redesigned version of Piccard’s FNRS-2.

A real legacy, remembered in fiction

Auguste Piccard died of natural causes at the age of 78 in 1962. The work that he began, and which his son continued, would lay the foundation for modern deep sea, ariel, and space exploration. His grandson also has considerable adventuring chops — Bertrand Piccard was the first person to complete a nonstop balloon flight around the globe. He was also the first person to complete a round-the-world solar-powered flight.

Piccard signing autographs in 1950. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

And while he isn’t as famous as Neil Armstrong, Auguste Piccard’s memory lingers in the popular imagination in some unusual ways.

European readers might see Piccard’s likeness in the face of Professor Cuthbert Calculus, Tintin’s physicist friend, in the enduringly popular comics created by Belgian cartoonist Herge. The artist had spotted Piccard on the streets of Brussels and promptly used his unmistakable looks as inspiration for Tintin’s inventor companion. But Herge had to make Professor Calculus shorter than Piccard, otherwise the character wouldn’t fit in the panel!

And if any Star Trek fans have been reading along, thinking that Piccard’s name and signature combination of smarts and courage sounds familiar, there’s a good reason for that.

Remember Piccard’s twin brother Jean? When Gene Roddenberry launched Star Trek: The Next Generation in the late 1980s, he named his next great Star Trek captain (some, including this journalist, would say the great Star Trek captain) after the brothers. Jean-Luc Picard is studious, reserved, and a scientist, but he’s also unflinching in the face of danger. Sound familiar?

And because our TV waves are making it out into space, something of Auguste Piccard is out there — boldly going, as he so often did, where no man has gone before.