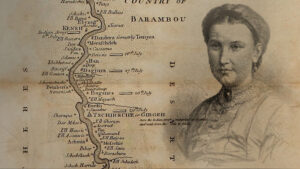

Lady Hester Stanhope exchanged a life of a wealthy socialite to forge her own path in the deserts of the Middle East. She pioneered archaeology in the Levant — an old term for Israel, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria.

Background

Born into privilege in 1776, Hester Stanhope came from a long line of politicians, prominent military officials, and accomplished scientists. Her father, Charles Stanhope, the 3rd Earl Stanhope, was not just an important member of the Whigs but also a noted mathematician and inventor. He created the first iron printing press and made improvements on many other tools.

Hester’s great-grandfather was a naval officer and last Chancellor of the Exchequer, James Stanhope (1st Earl). Most famously, Hester was the niece of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger. His time in office saw the world-changing years of the French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars.

Lady Hester Stanhope in Eastern clothing. Photo: Phrood/Wikipedia Commons

Hester’s upbringing as a high-born lady made her an asset to her uncle, who seemed to struggle with conversing and engaging well with his colleagues. Hester came to live with the Prime Minister. In exchange, she worked as the hostess in his household. She entertained his guests and charmed those around her. She blended in well with male company and received the nickname of “Amazon” by them, according to English Heritage — perhaps because she was almost six feet tall.

Her success in maintaining her uncle’s vital relationships led to her promotion as his private secretary. She stayed with him for more than two years. When he eventually passed away, she received an annual pension from the state to sustain her for the rest of her life.

Outwardly, she seemed content as an accomplished society woman. In private, she struggled. Her love life was a complete mess. She was not married, and her intense and passionate affairs with officers and politicians always ended in heartbreak. These and other personal tragedies prompted her to seek a life away from England for good. She chose the most unexpected of places: Lebanon.

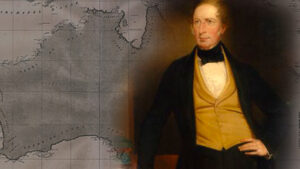

William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806). Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Pioneering archaeologist

Hester’s position as a society girl gave her the funds to travel to far-flung regions, including Greece, Constantinople, Egypt, and the Levant. She was the first English woman to enter the Great Pyramid and the ancient city of Palmyra in Syria. In Greece, she met the great English poet Lord Byron, who described her as a “dangerous thing,” full of wit and sharpness.

She was not one to hold back on her own opinions and often found herself in hot water for defying the conventions of the era. She smoked, rode camels, and wore men’s clothes. Some found her behavior unbecoming of a woman, while other locals appreciated her efforts to learn about their culture and highlight their complexities.

Her archaeology career began when she received an Italian manuscript that bore the supposed location of a treasure in gold coins buried somewhere beneath Tel Ashkelon, in modern-day Israel. Her 1815 search became the first ever modern archaeological dig in that region. While she did not find the hoard, she unearthed many valuable artifacts, including an important Roman statue.

‘Queen of the Desert’

Instead of making her home in an elaborate villa or great manor house fit for a noblewoman, she moved into a former monastery atop Mount Lebanon. Here, she became the unofficial ruler of the districts around her. Locals and visitors respected and even feared her. Some thought she was a witch.

Palmyra in Syria before the Civil War. Photo: Pavlov Valeriy/Shutterstock

She nurtured relationships with the local Bedouin and with the Ottoman rulers in the area. She tried her best to show them that she focused on preserving their culture rather than stealing treasures like the British often did.

The decline

Eventually, she experienced a prolonged spell of bad luck. She wracked up considerable debt to the Ottomans, which forced the British government to intervene. When her pension was about to be garnished to pay off the debts, she wrote a series of feisty letters to officials and even to Queen Victoria herself. Unfortunately, these financial issues persisted until she died in 1839.

She turned from a vibrant, sophisticated woman into a shell of her former self because of depression and early-onset Alzheimer’s. She shaved her head, wore a turban, and saw people less and less. Her servants betrayed her by stealing from her.

After she died at age 63, her tomb suffered from earthquakes and vandalism. Despite the sad end to her life, her legacy as Victorian England’s Queen of the Desert remains.