Ulugh Muztagh (6,973m) is an extremely remote peak on the northern Quinghai-Tibetan Plateau in Western China. It remained a mystery for nearly a century before a team of American and Chinese climbers climbed it in 1985. Called the Great Icy Mountain in the Turkic language, it sits in a high desert where few people go.

After his 1895 journey, English explorer George Littledale guessed Ulugh Muztagh was over 7,723m, making it one of the world’s highest peaks. The 1985 expedition climbed it and measured its true height.

Shipton’s idea

The idea to climb Ulugh Muztagh started in 1966. Robert H. Bates was stuck in a tent with Eric Shipton during a storm on Mount Russell in Alaska. Bates asked Shipton what he’d do differently if he could start over.

Shipton, who’d spent years on Everest, said: “I wouldn’t spend six years trying to climb Mount Everest. That’s too long for any mountain.” Instead, he said he’d go for Ulugh Muztagh, a peak in Central Asia. He described it as “a big mountain — nobody knows how high — reached in the 1890s by an Englishman.”

He described it as harder to get to than Antarctica, surrounded by high, empty land with no people nearby. Shipton and his friend Bill Tilman had wanted to climb it, but political restrictions and logistical difficulties had deterred them.

Bates, who’d climbed big mountains like K2, loved the idea. In 1973, Bates teamed up with Nick Clinch, another climber who’d heard Shipton’s stories. They decided to find the mountain, measure it, and climb it.

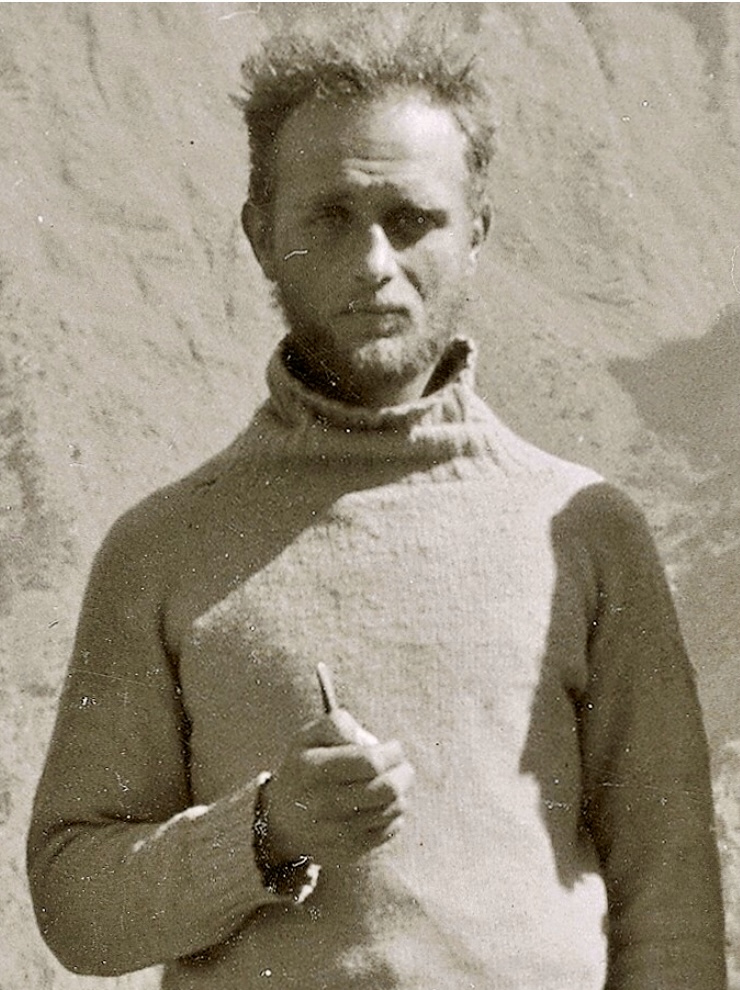

Eric Shipton in 1936. Photo: Wikipedia

Previous journeys to Ulugh Muztagh: The Littledales

In 1896, British explorer George R. Littledale and his wife Teresa described Ulugh Muztagh as towering and glacier-covered, and suggested that it could be as high as Everest. The Littledales made three major journeys between 1890 and 1895. During their first trip, they crossed the Pamirs. On the second, they crossed Central Asia from Samarkand to Peking, and the third journey — which took 12 months — traversed Tibet.

In 1895, the couple passed Ulugh Muztagh while attempting to reach Lhasa, and they estimated the mountain’s height. Their estimate was unverified and based on visual observation, but it contributed to the mountain’s mystique.

A base of magma

Formed by the ancient collision of continents that uplifted the Himalaya and Kunlun ranges, Ulugh Muztagh’s base is reinforced by hardened magma, distinguishing it from the eroded surrounding landscape. This unique geology led scientists to speculate that Ulugh Muztagh could be a volcano. The 1985 expedition realized that it was not a volcano, but it does have a base strengthened by ancient magma intrusions.

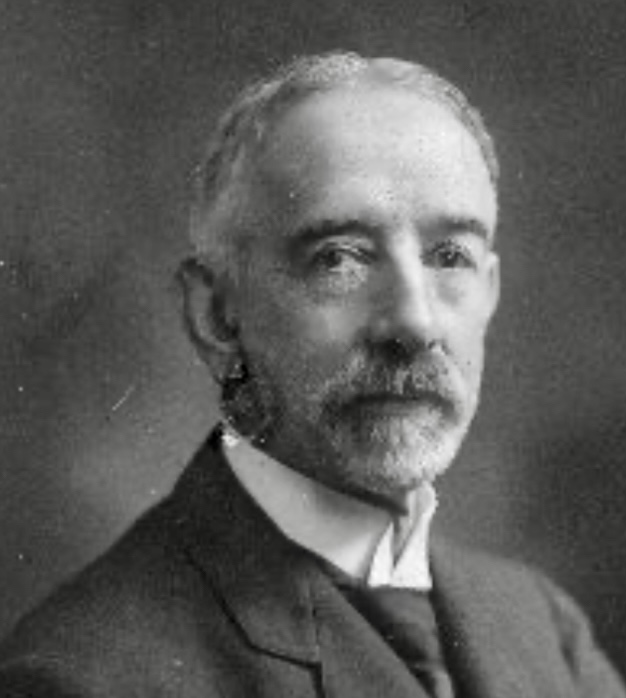

George Littledale. Photo: Wikimedia

Getting a permit

Bates and Clinch spent several years trying to get to Ulugh Muztagh. The mountain was in a part of China that had been closed to foreigners since the 1950s. They asked for permission many times, even suggesting a joint expedition with China and Pakistan, but got nowhere.

In 1979, Bates went to Beijing to ask in person, but was told the area wasn’t open. They kept trying until January 1985, when another group got permission. A determined Clinch flew to Beijing immediately, and — after two more trips — received approval for a joint American-Chinese expedition on May 30, 1985.

‘A geriatric expedition, but a damn good one’

Clinch put together a team of eight Americans, calling it “a geriatric expedition, but a damn good one.” Robert H. Bates, 74, would survey and measure the mountain. Nick Clinch was the organizer and had led the first climb of Hidden Peak in 1958. Pete Schoening was in charge of gear and was well known for saving six climbers on K2 in 1953. Tom Hornbein, the team’s doctor and climbing leader, was famous for climbing Everest’s West Ridge in 1963. Hornbein planned the route and organized supplies during the expedition. Jeff Foott and Dennis Hennek were strong climbers who would carry heavy loads and remain ready for the summit. Geologists Peter Molnar and Clark Burchfiel joined to conduct a scientific study of the mountain.

The Chinese team featured 16 climbers and 27 support staff, including climbers Hu Feng Ling, Zhang Baohua, Ardaxi, Mamuti, and Wu Qiangxing. Leaders Wang Zheng Hua and Lu Ming ran logistics, and interpreter Guo helped with communication.

This was the first American-Chinese climbing expedition, and the first time foreigners were allowed in southern Xinjiang in 30 years.

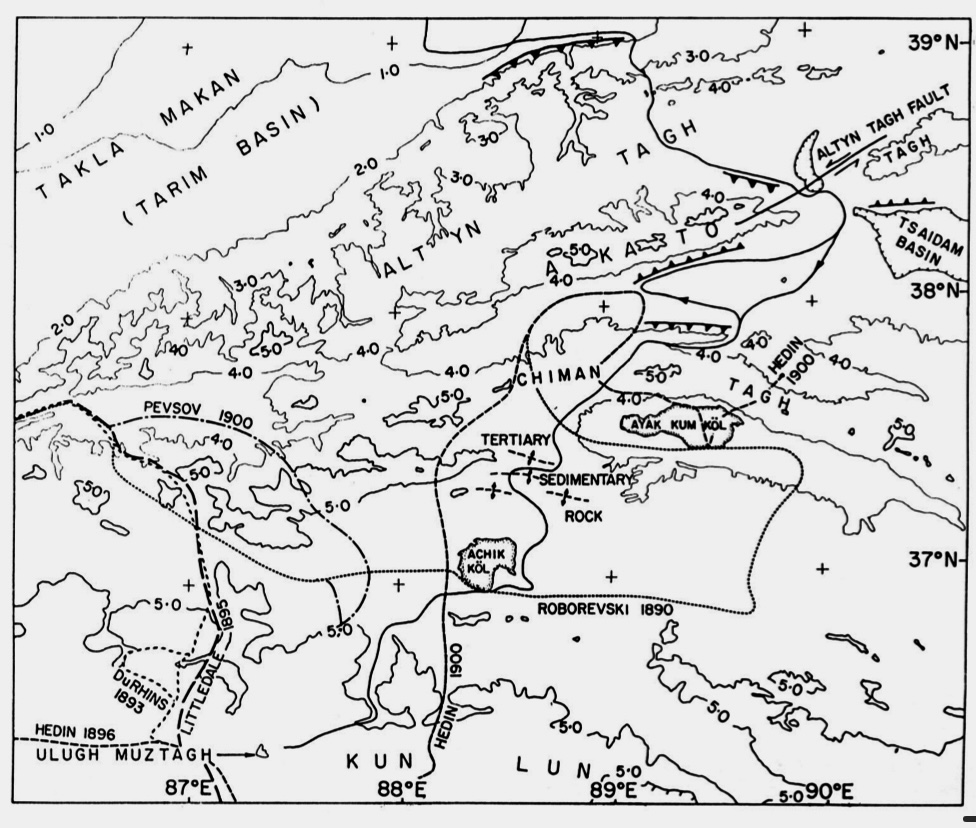

The northern edge of the Tibetan plateau, showing the 1895 route to Ulugh Muztagh, bottom left. Photo: Peter Molnar

A long trip

On Sept. 11, 1985, the Americans flew from San Francisco to Beijing with 87 bags of gear, including survey tools like a Doppler satellite surveyor, a Uniranger, and a Kern T-2 theodolite.

The 1,100km trip to the mountain took 10 days. Seven army trucks, three Land Rovers, and two jeeps crossed deserts and mountains. They stopped in Korla, a city of 120,000 with hospitals and factories, and Ro-jeng, where Marco Polo had once passed through. They crossed the Altyn Tagh Range and reached an asbestos mine, the last stop before the desert. They saw yaks, bears, antelope, and wolves near Acchikul Lake.

On October 2, after a tough drive up a canyon, they set up Base Camp at 5,300m on the mountain’s east side. They immediately encountered a problem: the satellite surveyor’s antenna was missing. A Chinese Mountaineering Association jeep team had to rush a new one to them.

6,973m Ulugh Muztagh, left peak. A Finnish party first climbed the slightly lower subsummit, Ulugh Muztagh II, at 6,925m on the right, in 2003. Photo: Sg.trip.com

The survey

The plan was to train and acclimatize at base camp, but Wang Zheng Hua wanted to start climbing. The Chinese climbers who’d tried the peak in 1984 picked the route. They set up Camp 1 at a glacier’s edge, and soon they were carrying supplies to Camp 2, approximately 10km up the glacier.

Bates stayed at base camp to run the survey because he could no longer carry heavy loads. Molnar and Burchfiel, used to high altitudes, carried gear with Foott, Hennek, and Hornbein. Schoening and Clinch got sick, slowing them down. Hornbein planned routes and made sure food and gear were in the right spots.

The survey went on despite strong winds. They set up a 10,460m baseline in the desert and used the satellite surveyor to catch signals. Later, Molnar calculated the peak’s height as 6,987m, “with an estimated possible error of 6 to 10 meters.” The altitude was significantly less than Littledale’s guess, but still a major challenge.

Ulugh Muztagh, looking west in late afternoon from Camp 2 in the foreground. Photo: Peter Molnar, 1985

The first ascent

Ulugh Muztagh was a tough climb. Its glaciers had hidden crevasses, and loose snow could slide. Steep ice walls and bad weather only made it harder.

By mid-October, snowstorms hit. Camp 2 was buried, and the avalanche risk was high. On October 13, Schoening, Hornbein, and Burchfiel put in ice screws for Camp 3, but wind and snow soon stopped them. Clinch, who had a bad cold, went back to base camp.

Schoening and Hornbein reached 6,200m to store supplies, and a mix-up about who would lead the Chinese to the summit led Foott and Hennek to come down. On October 20, good weather allowed the Chinese climbers at Camp 3 to move to Camp 4, close to the summit.

On October 21, five Chinese climbers — Hu Feng Ling, Zhang Baohua, Ardaxi, Mamuti, and Wu Qiangxing — reached the summit at 7:28 pm. The team at base camp celebrated, but joy turned to worry as it got dark. The summit climbers took a different way down and ran into trouble.

Hu Feng Ling climbing Ulugh Muztagh. Photo: Summitpost

The descent

During the descent, Hu and another climber fell more than 500m. The next morning, Schoening’s team spotted them, one climber lying still and the other trying to help. They gave up their summit climb to attempt a rescue.

Clinch, coming from Camp 2, also helped. Hu had frozen feet and bruises, and his friend was also hurt. Hornbein and Hennek took care of them at Camp 2. Guo, the interpreter, was touched and said, “Americans must be the kindest people in the world.”

In the end, there was no time for another summit try, and on October 23, everyone left the mountain.

Carrying Hu was slow and painful, and they didn’t reach base camp until October 24. The team packed up and drove back, cold and low on food. In Ro-jeng, they were greeted with dancing girls, and in Korla, thousands cheered their return with firecrackers and flowers. In Urumchi, a big dinner in the Great Hall of the People included a roast sheep to show friendship.

Ulugh Muztagh was not as tall as hoped, but this was an important climb, showing how people from different countries could work together, even when things got tough. For Bates and Clinch, the climb was for Shipton, who loved unknown peaks. They toasted him, happy to have reached his dream mountain.

The 2003 Finnish expedition to Ulugh Muztagh. They made the first ascent of Ulugh Muztagh II. Photo: Summitpost

Ulugh Muztagh remains one of the world’s most remote and rarely climbed peaks, with only a handful of documented ascents since 1985.

We recommend Peter Molnar’s report in the Alpine Journal: Ulugh Muztagh: The Highest Peak on the Northern Tibetan Plateau.