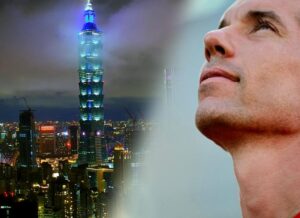

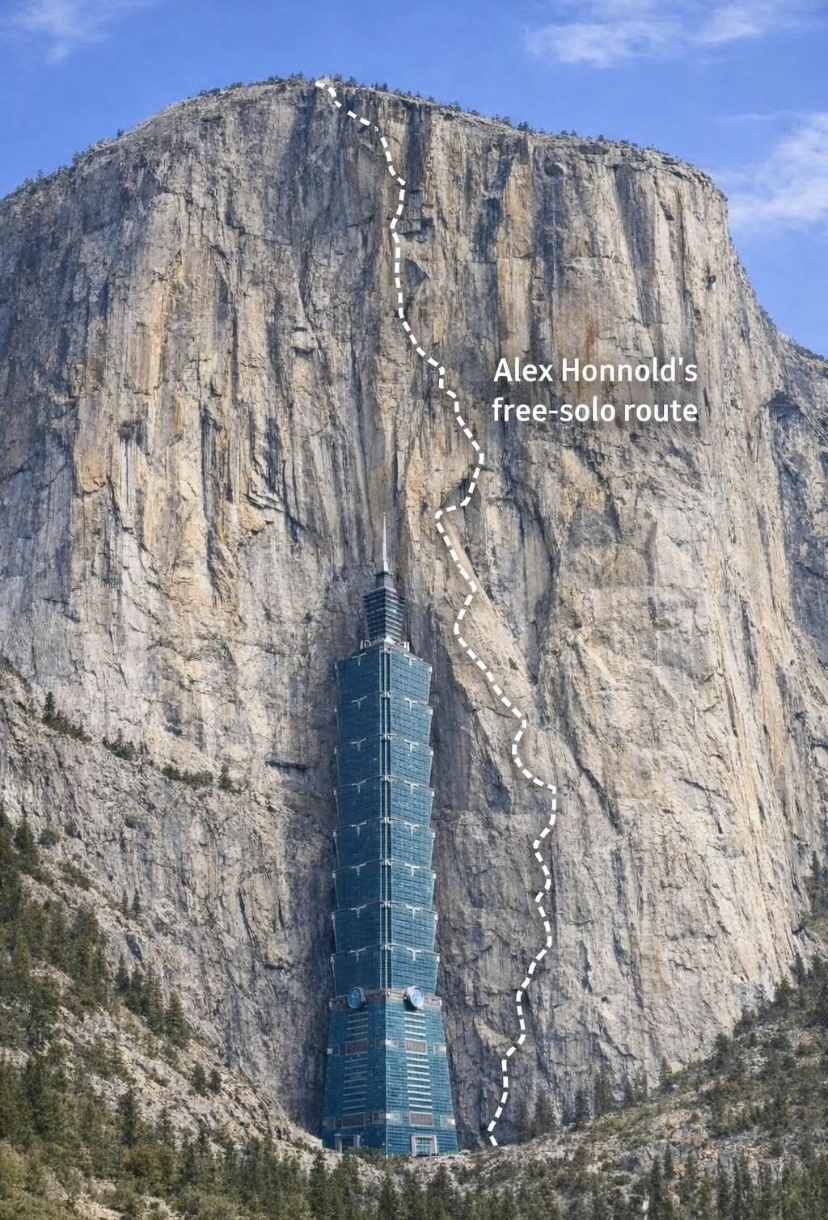

When Alex Honnold free soloed the 508m Taipei 101 skyscraper last month in just 1 hour and 31 minutes, the internet lost its mind. Headlines screamed “Greatest Free Solo Ever,” Netflix viewership exploded, and yes, it was wild to watch live.

But as mind-blowing as that urban stunt was, it doesn’t touch what he did on El Capitan’s Freerider back in 2017. That Yosemite granite wall is nearly twice as tall (884m of sustained, exposed 5.13-ish climbing), with way more complex sequences, tiny holds that crumble if you breathe wrong, and zero margin for error over hundreds of meters of air. No beams to grab, no predictable patterns, just you, the rock, and whatever mental steel you’ve built up over years of prep. That’s the kind of free solo that redefines what’s possible on natural stone.

So while the skyscraper headlines fade, let’s revisit some of the most iconic free soloists in rock climbing history beyond Honnold, the pioneers who pushed the absolute limits of unprotected climbing.

Honnold’s Taipei 101 free solo vs. his Freerider free solo. Photo: Social media

Free soloing

Writing about free soloing feels a bit like analyzing a hurricane from an armchair. Even if you’ve watched videos, read several books, and imagined the vertigo, you never truly know the rush or the dread. Still, that’s part of what makes this topic so compelling. It’s a window into a world most of us will never enter, yet it stirs something primal in all of us.

Free soloing means climbing without ropes or other protection gear, or any aids beyond your shoes for grip and chalk to keep your hands dry. It’s you against the rock, pure and simple. No belay partner, no bolts to clip, and no second chances if you slip. A fall is game over.

Giving up everything

Unlike free climbing (where you use natural holds but have a rope for safety), or aid climbing (pulling on gear to progress), free soloing strips away everything. It’s the ultimate test of body and mind, where even a whisper of doubt can unravel you. As climber Alexander Huber wrote in his book Free Solo: Klettern ohne Sicherung und ohne Grenzen (“Free Solo: Climbing without protection and without limits”): ”Grab the stopwatch and you have speed climbing. Give up aid climbing methods, and you have free climbing. Give up everything, and you arrive at free soloing.”

Free solos on rock can happen in two main ways: on-sight (climbing the route for the first time without any prior rehearsal or beta, no top-roping, no watching others, no notes on the moves), or rehearsed (the climber has climbed the route multiple times before, often roped, to memorize every hold, sequence, and rest spot). Onsight solos carry an extra layer of raw commitment because there’s zero room for error in figuring out the puzzle on the fly.

Free soloing isn’t just difficult, but it’s a cocktail of physical precision, mental fortitude, and uncontrollable variables that can turn a climb into tragedy in a heartbeat. Imagine hanging by your fingertips on a crumbly hold, wind whipping at your back, 500m of empty air below you. One gust, one loose flake of rock, and it’s over. External dangers may appear at any moment. Sudden rain slickens the rock, a bird startles you in mid-move, a snake suddenly appears from a small crack, or fatigue cramps your calves.

Preparation is everything. But mental strength is almost everything, too. Climbers often rehearse routes obsessively, sometimes for years, climbing them roped dozens of times to memorize every nuance, such as the texture of a hold, the precise sequence of moves, and even how the sun warms the stone at certain hours. It’s about mastering fear through preparation, turning terror into focus. Climbers describe entering a flow state where the world narrows to the next hold, the next breath.

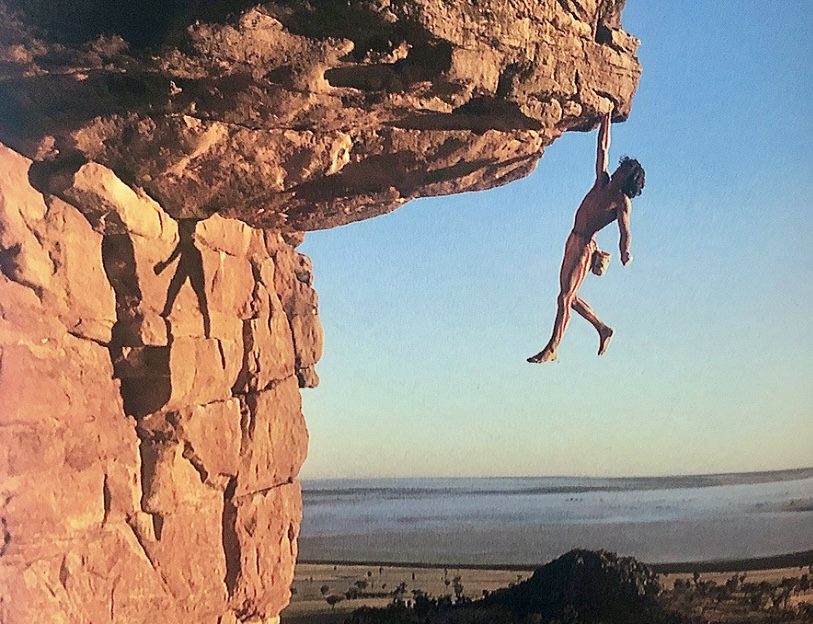

Alex Honnold on the monster off-width section of ‘Freerider’ during his free solo ascent of El Capitan. Photo: Tom Evans/ElCapReport.com

The point of no return

Free solo is also about crossing that point of no return: the critical moment on the route where the moves you’ve just done become too hard or too insecure to safely reverse. From there, downclimbing is no longer realistic, and the only way out is up.

The point of no return can come early, sometimes just 10m or 20m off the ground on overhanging or technical lines, or higher up. However, once you’ve passed it, hesitation turns deadly. Free soloers manage fear not by ignoring it, but by building mental armor. Deep breaths to calm the pulse, rational self-talk to push through doubt. Many have paid the ultimate price, and that knife-edge tension is what makes every climb a wild ride for the soul.

Compiling a list of history’s greatest free soloists and their most iconic climbs feels subjective, almost arbitrary, and it would never be absolute. But let’s try, anyway.

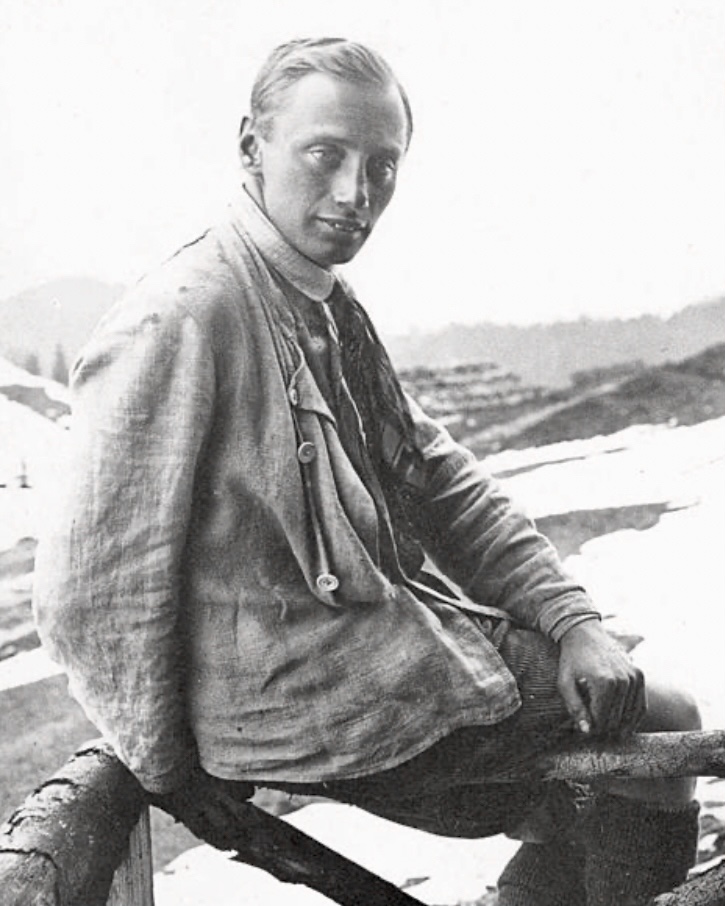

Paul Preuss. Photo: Archiv Deutscher Alpenverein/Wikipedia

Paul Preuss, the ‘father’ of free soloing

Paul Preuss was an Austrian climber and philosopher from the early 20th century, recognized as a pioneer of free soloing. He advocated a radical purity in climbing, believing that a climber should rely solely on his own abilities, without external aids such as ropes or pitons. Skill, judgment, and physical ability should overcome difficulties, not equipment.

He applied this ethic to free soloing and completed approximately 300 solo ascents out of 1,200 total climbs. Preuss is the ideological foundation of the sport. In the early 1900s, he argued that a climber should only go up what they can also climb back down without gear.

His most notable free solo was the first ascent of the east face of Campanile Basso (also known as Guglia di Brenta) in the Brenta Dolomites of Italy in 1911, when he was 25 years old. He climbed the route on-sight. True to his strict personal ethics, he descended the same route by down-climbing it without ropes. Preuss died in 1913 while attempting a new solo route on the north ridge of Mandlkogel in Austria, falling from a great height. (We recommend reading Paul Preuss: Lord of the Abyss, by David Smart.)

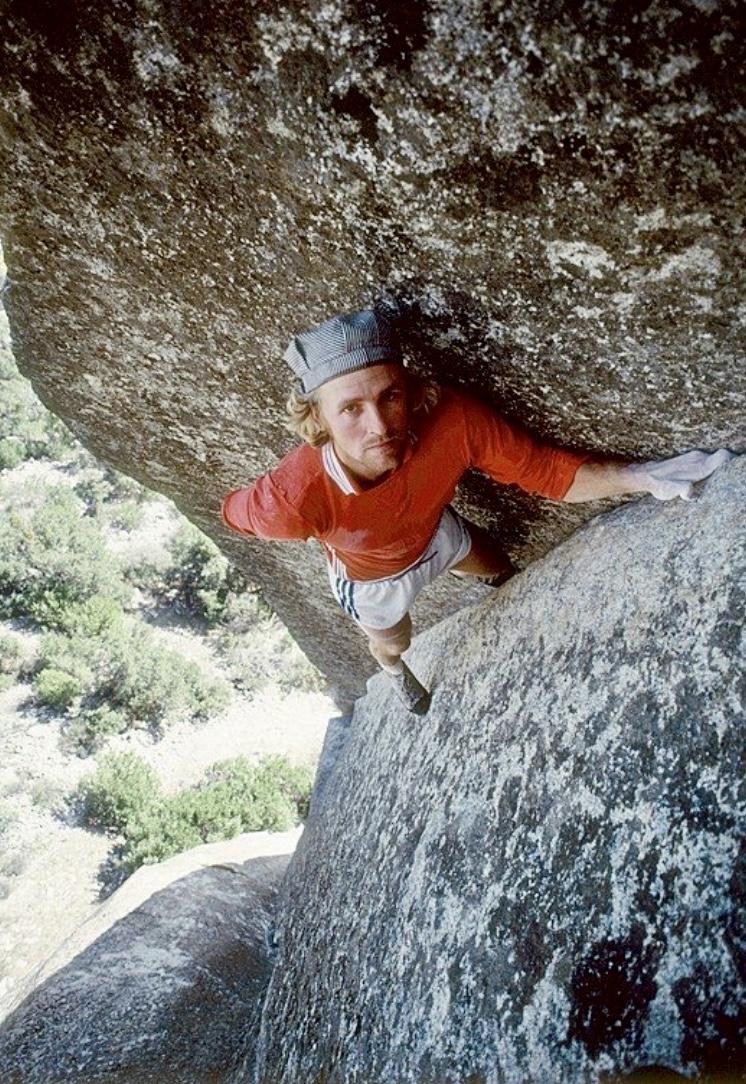

John Bachar free soloing New Dimensions. Photo: Phil Bard

John Bachar, the first icon

John Bachar was one of the most influential American rock climbers of the late 1970s and 1980s. A legend in the sport, he brought a professional, athletic rigor to the discipline of free soloing in Yosemite.

One of his most impressive free solos was on the 100m-long New Dimensions route (5.11a), a classic multi-pitch crack climb on Arch Rock in Yosemite. This groundbreaking climb pushed the boundaries of what was considered possible without ropes at the time.

Bachar treated highball bouldering like boot camp for these solos, knocking out hundreds of hard routes with little prep, basically inventing modern free solo training, until a fall claimed him at age 52 in 2009, while free soloing a route on Dike Wall, a climbing area near Mammoth Lakes in California. No one witnessed the accident, but other climbers nearby heard the fall and reached him quickly. He was taken to a hospital but succumbed to his injuries shortly after.

Wolfgang Gullich, the technical master

Germany’s Wolfgang Gullich brought the extreme difficulty of sport climbing to the world of soloing, and took it to another level. In 1986, he pulled off the first-ever free solo of a 7c (5.12) route with Weed Killer at Raven Tor in England. That climb was a huge psychological leap at the time.

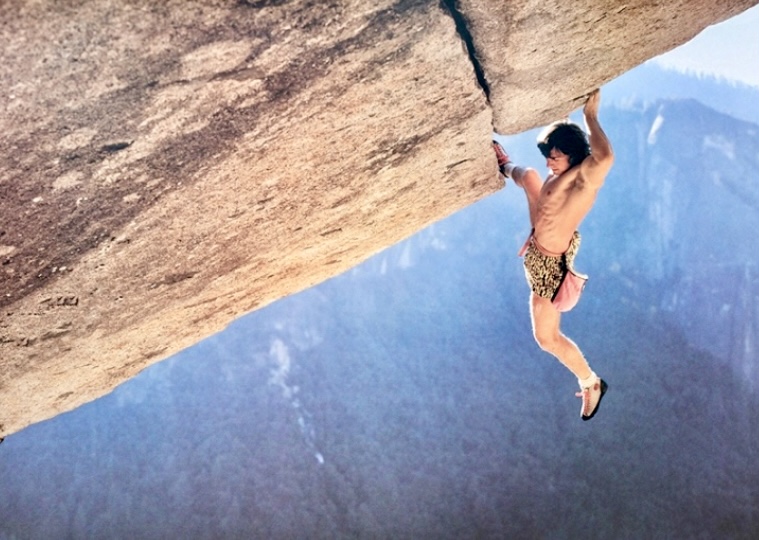

The same year, he did his most iconic ropeless climb: Separate Reality in Yosemite. The image of him hanging from a horizontal roof above the ground is one of the most iconic photos in climbing history.

Tragically, Gullich died way too young at 31, in a car accident on a German highway in 1992.

Wolfgang Gullich during the first free solo ascent of ‘Separate Reality’ in Yosemite. Photo: Heinz Zak

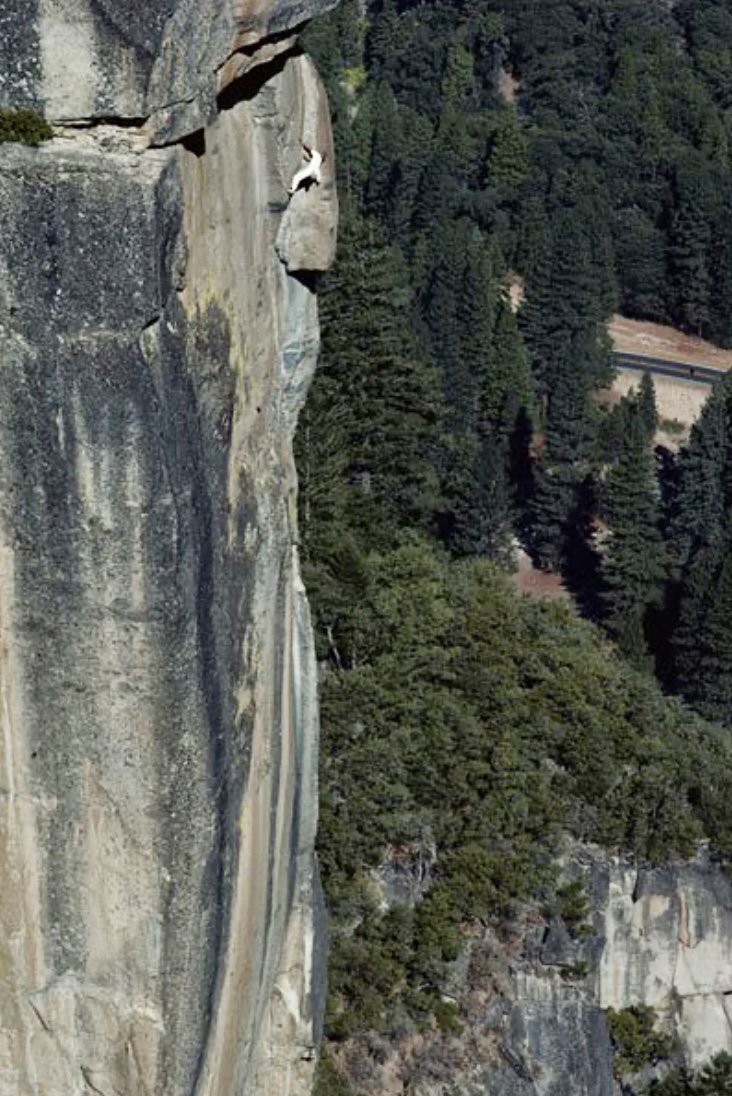

Peter Croft, the endurance king

Canadian Peter Croft grew up climbing in British Columbia’s Squamish and became one of the most respected figures in big-wall free climbing and free soloing from the 1980s onward. He’s known for his incredible efficiency, endurance, and calm approach to long, demanding routes, especially on Yosemite’s granite. He treated multi-pitch classics like they were casual outings. What really put him on the map was his free soloing. He started free soloing early in Squamish and Washington state, knocking off overhanging 5.11s like ROTC at Midnight Rock in 1984.

But his big breakthrough came in Yosemite in 1987, when he became the first person to free solo Astroman (a sustained, exposed 5.11c on Washington Column) and then linked it with a free solo of The Rostrum (another classic 5.11 multi-pitch) on the same day.

That link-up stunned the climbing world. Royal Robbins, one of the old Yosemite greats, called it astonishing mastery rather than just bold luck. Croft had already soloed Astroman alone a little earlier, and the combo showed he could handle long, technical, committing terrain ropeless, with total control.

Croft’s style was low-key and personal because he saw free soloing as an intimate thing, not something to hype or film much. He avoided the spotlight, stayed humble, and just kept moving over rock better than almost anyone.

Peter Croft, during one of his free solo ascents of The Rostrum. Once he free soloed it three times on the same day. Photo: John Bachar

Dan Osman, the mid-air double dyno master

Dan Osman was an American extreme sports pioneer and rock climber, known for his high-risk approach to the mountains. He lived a bohemian lifestyle as a carpenter while pushing the limits of speed and safety in the 1980s and 1990s. Beyond climbing, he invented “rope jumping”: controlled free-falls using dynamic climbing ropes to catch himself in a massive pendulum swing.

With his signature long hair and explosive style, he became a cult figure through the Masters of Stone film series, bringing extreme climbing to a mainstream audience.

Osman’s most iconic free solo was on Bear’s Reach at Lover’s Leap, California, in 1997. He sprinted up the roughly 120m route (graded 5.7) in just 4:25 minutes. The climb became a viral legend for its mid-air “double dyno,” a terrifying leap where he completely detached from the rock. He died in 1998 at age 35 in Yosemite National Park when a rope system failed during a record-breaking jump. A post-accident investigation concluded that the failure was attributed to rope-on-rope friction that melted the line.

Catherine Destivelle, the female pioneer

Born in Algeria and raised near Paris, Catherine Destivelle of France was the most famous female climber of her era. While her peers often relied on brute strength, she was celebrated for her balletic grace and an eerie, unshakable calm at heights that would paralyze most. Through breathtaking documentaries, she brought the terrifying beauty of solo climbing to a global audience, making the most technical movements look effortless.

Her most impressive pure rock free solo took place in 1987 on the sandstone cliffs of the Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali. Filmed for the legendary documentary Seo, Destivelle climbed technical, overhanging walls in the heart of Dogon country with zero equipment, no ropes, no harness, and no margin for error.

Beyond rock, Destivelle’s legacy was cemented in the high Alpine, where she became the first woman to complete the winter solo Triple Crown of the Alps: the Eiger, the Matterhorn, and the Grandes Jorasses. In 2020, she was the first woman to receive the Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement Award.

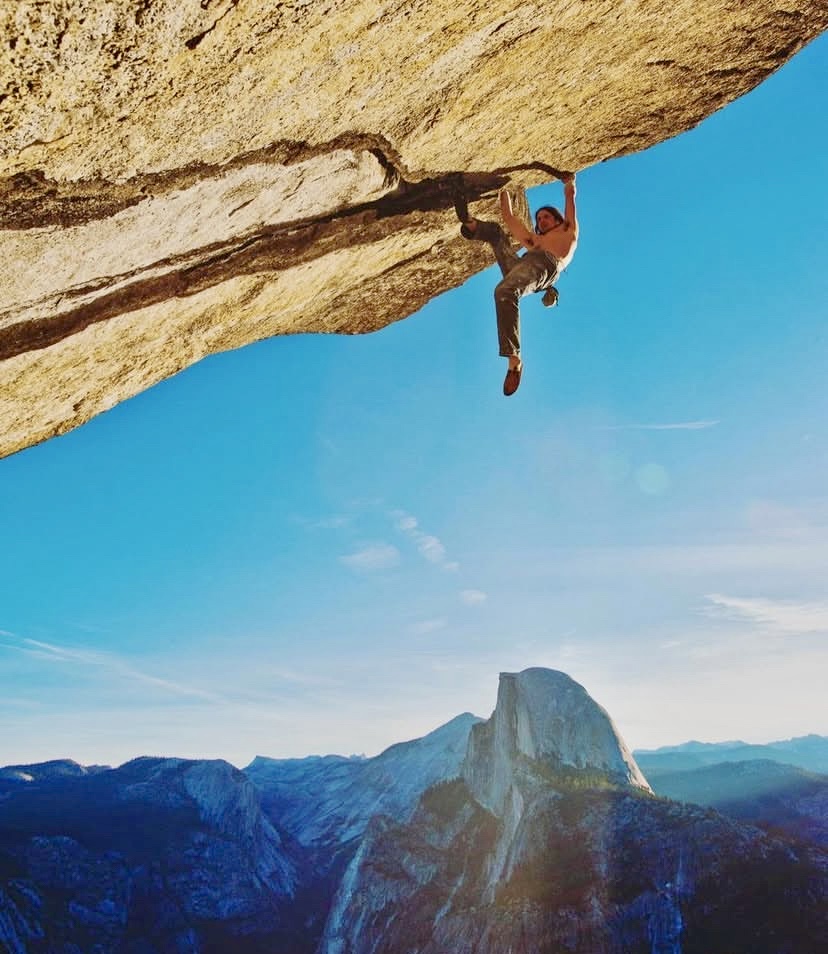

Dean Potter, the FreeBASE visionary

If climbing had a mystic, it was Dean Potter. Known for his imposing physical presence and a gaze that seemed to pierce the rock, Potter inhabited what he called The Dark Arts, which was a blurred communion between free soloing, high-lining, and BASE jumping. For Potter, the void was a space of meditation where fear transformed into absolute mental clarity.

His most visually terrifying achievement took place on Heaven, a brutally overhanging crack jutting out like a granite diving board at Glacier Point. Potter navigated this technical roof (5.12d/5.13a) with animalistic power and icy precision. As the pioneer of FreeBASE, he later integrated the parachute as a solo climber’s only safety system on higher walls. (Notably, Potter didn’t wear a parachute on Heaven, as the terrain below was unsuitable for a parachute deployment.) Potter lived on the impossible edge between total freedom and the ultimate fall until his tragic passing in 2015 during a wingsuit flight.

Dean Potter makes the first free solo ascent of ‘Heaven’. Photo: Jimmy Chin/Instagram

Steph Davis, a bird that can’t be caged

U.S. climber Steph Davis redefined the modern era of free soloing by blending technical mastery with the freedom of flight. A former classical pianist, Davis brought the discipline of the keyboard, focusing on rhythm and repetitive precision, to the vertical world.

She first made history in 2005 as the first woman to summit Torre Egger in Patagonia. Often described by her partner as a “bird that simply cannot be caged,” Davis transitioned from an elite academic path to the climbing life. She became a female pioneer of FreeBASE climbing.

Her most defining free solo on rock came in 2007, on the East Face of Longs Peak, Colorado, known as The Diamond. Davis became the first woman to free solo this wall via the technical Pervertical Sanctuary (275m, 5.11a). For Davis, soloing wasn’t a gamble, but a way to belong entirely to the mountain, stripping away everything until only the movement and the air remain.

”For me, the thought of getting hit by icefall or falling from a rock face are totally acceptable possibilities,” wrote Davis in her captivating book High Infatuation. “The idea of being hurt by a person is not. It always surprises me to hear people talk about climbing being dangerous. I have always felt safest alone on the side of a hard-to-reach wall or mountain. Although I understand that I could die in the mountains, I trust the hand of nature, and I know it will do me no harm.”

Alain Robert, the mutant with vertigo

Long before he became the world-famous “French Spider-Man” for scaling skyscrapers, Alain Robert was a pure rock mutant. His story is a medical anomaly. Following several catastrophic falls early in his career, Robert was left with a 66% technical disability and suffers from chronic vertigo due to inner-ear damage.

Instead of retiring, he transformed his fractured balance into surgical precision, becoming the most audacious free soloist of his generation. For Robert, the vertical world was the only place where his body truly made sense.

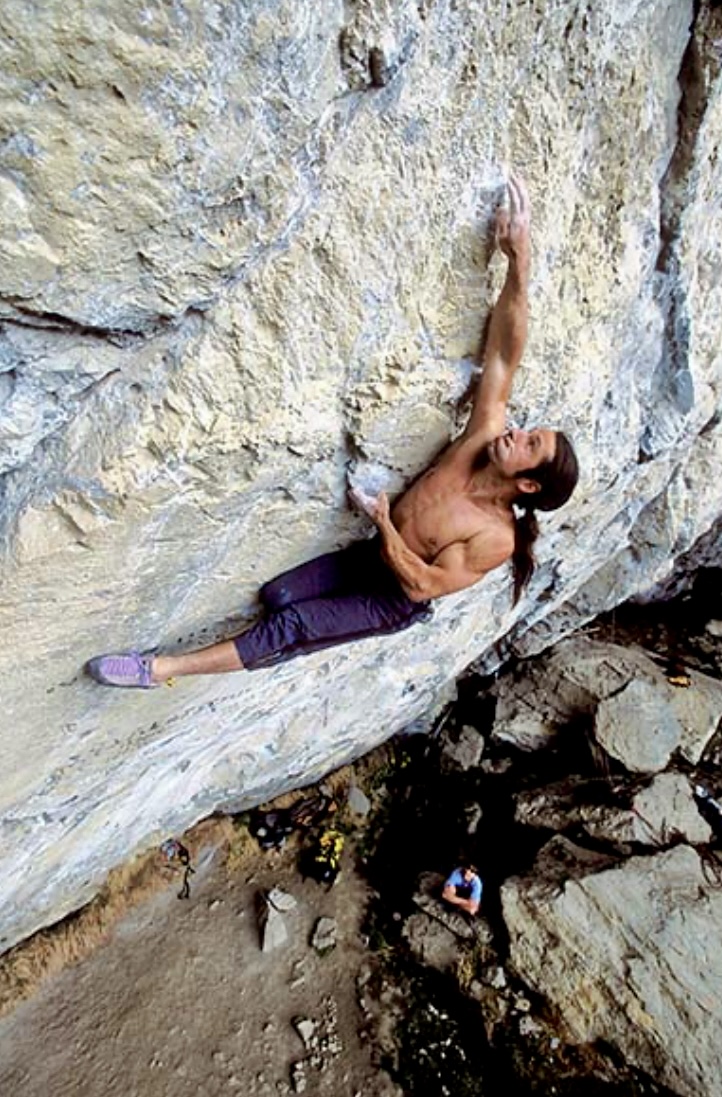

In 1991, he etched his name into history with the free solo of Compilation in Ombleze, France. Graded at 8b (5.13d), it was the world’s first 8b free solo, a level of technical difficulty so extreme, with or without a rope, that it wasn’t matched by the rest of the climbing world for over a decade. While his building climbs brought him global fame, his legacy on the rock remains the gold standard for pure technical difficulty without a net.

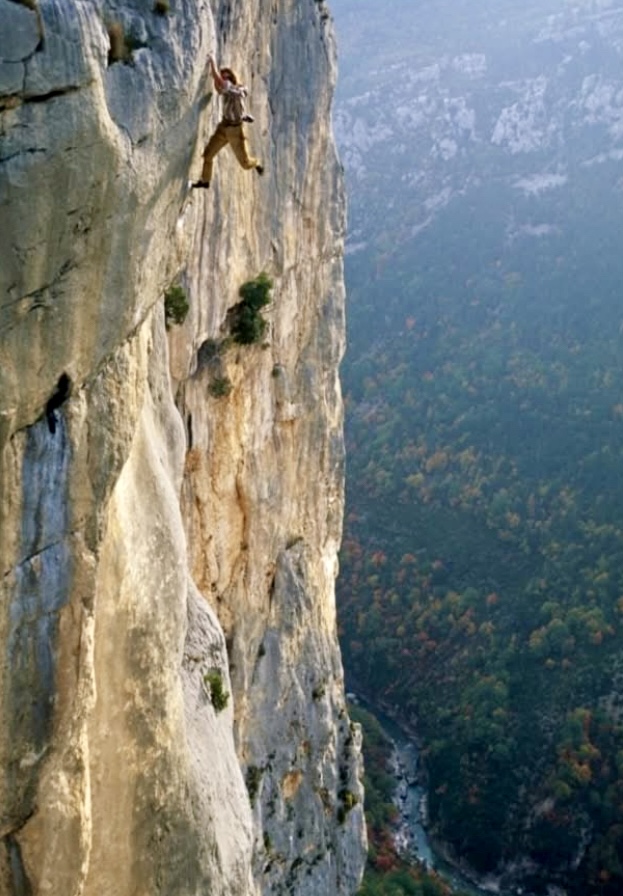

Alain Robert during a hard free solo climb in Verdon. Photo: Alain Robert

Alexander Huber, the physicist of the void

While other climbers sought adrenaline or spiritual connection, Alexander Huber of Germany approached the abyss with the cold, calculated mindset of a laboratory. A trained physicist, Huber stripped his ascents of all emotion, transforming the gut-wrenching terror of free soloing into a series of equations involving friction and centers of gravity.

To him, climbing without a rope was an exercise in mathematical precision. If the preparation was perfect and the technical execution flawless, falling simply wasn’t a variable in the equation.

His technical masterpiece occurred in 2004 with the free solo of Kommunist (8b+/5.14a) in Austria. At the time, free soloing at this grade was considered a physical impossibility, as the holds are so microscopic that a slip of a single millimeter results in certain death.

In 2008, he applied his “up and down” philosophy to the massive 400m South Face of the Grand Capucin in the French Alps. By free soloing the legendary Swiss Route and then downclimbing it without any external aid, he honored the purest traditions of climbing, following in the ethical footsteps of Paul Preuss.

We highly recommend reading two compelling books by Alex Huber: Free Solo. Klettern ohne Sicherung und ohne Grenzen (in German and Spanish editions); and Die Angst- Dein Bester Freund (“Fear, Your Best Friend”), unfortunately available only in German.

Alexander Huber free soloing ‘Kommunist’. Photo: Heinz Zak

Hansjorg Auer, the quiet revolutionary of the Dolomites

Austrian climber Hansjorg Auer possessed a rare, humble intensity, preferring the silence of the high mountains to the noise of fame. In 2007, he achieved what many still consider the most audacious big-wall free solo in history on the massive South Face of the Marmolada in Italy.

Without telling a soul and carrying only a small bag of chalk, Auer stepped onto the rock to face Via Attraverso il Pesce (“The Fish Route”), a terrifying 850m limestone wall.

Moving with a speed that defied the technical difficulty, Auer blasted through the 37-pitch route in just 2 hours and 55 minutes. Graded at 7b+ (5.12c), the route is famous for its “Fish” niche: a shallow hole in the middle of a smooth, vertical sea of limestone where the exposure is absolute. Though he later became a world-class alpinist, this accomplishment on the Marmolada remains his masterpiece.

Auer was a man who lived for the purity of the mountains until his tragic passing in a 2019 avalanche.

Hansjorg Auer free soloing the ‘Fish Route’. Photo: Collection of Hansjorg Auer

Climbing has many more historic free solos: John Yablonski’s wild solos of Leave It to Beaver (5.12a) and Spiderline (5.11d), capturing the Stonemasters’ chaotic intensity, and John Long’s foundational pushes in Joshua Tree. The list extends to Stefan Glowacz on the spectacular roof of Kachoong (5.10d, 7b) in Australia, Ron Kauk’s bold lines on Middle Cathedral, and Michael Reardon’s prolific speed solos, along with countless unsung ascents that quietly redefined personal limits.

With all free solos, one question pulls at the edges of every ascent: What does it mean to stand at the absolute limit of human capability and choose to step forward anyway?