In the far northwest of Nepal lies a little-known area full of sensational peaks. The history of climbing in the Gurans Himal features peculiar characters and some fantastic stories.

Gurans Himal

The Gurans Himal is a small subrange of the Himalaya, made of two subsections. One, the Saipal area east of the Seti River, whose highest peak is Saipal (7,030m). Two, the Yoka Pahar area west of the Seti. It contains Api Main (7,132m), Api West (7,076m), Rokapi (6,468m), Jethi Bahurani (6,850m), Nampa (6,729 or 6,755m), and Bobaye (6,808m).

Parts of the northwestern Himalaya. Photo: Himalayan Journal

First western explorers

Several British expeditions ventured into the region in the late 19th century. English doctor, mountaineer, and explorer Tom George Longstaff investigated the Nampa Glacier in 1899. Longstaff went on to explore Tibet in 1905, traveling across the Tinkar Valley and entering Tibet via the Lipu Pass. Two years later, in India, Longstaff and three partners summited the highest peak ever climbed at that time, 7,120m Trisul.

Explorer A. H. Savage Landor (centre) with his cats Kerman and Zeris, with whom he traveled on some expeditions. Photo: Wikipedia

Arnold Henry Savage Landor, an English writer, painter, anthropologist, and explorer also explored the area. In 1896, so he said, he was captured and tortured in Tibet — a claim now considered spurious.

At any rate, Landor survived and wrote two books about northwestern Nepal, In the Forbidden Land and Tibet and Nepal. These were some of the earliest works about the Himalaya.

For much of his life, he maintained a breakneck travel schedule. In 1901, the eccentric Landor traveled from Russia to India, riding on horseback through Persia with his two cats.

The Swiss expedition

In 1936, the Swiss Scientific Society promoted a three-man Swiss Himalayan Expedition. It included geologist Arnold Heim, his student Augusto Gansser, and noted mountaineer Werner Weckert. They aimed to study the Himalaya for eight months. But just three days into the expedition, Weckert came down with appendicitis and had to be evacuated.

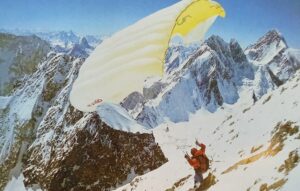

Heim and Gansser continued to explore. They crossed the “forbidden border” into Tibet and onto the Api Glacier. They were probably the first people to ski in the region.

On June 28, 1936, Gansser decided to head to Mount Kailash with two Tibetans and a Sherpa porter. Heim stayed in Nepal.

Arnold Heim (left) with Augusto Gansser during their exploratory expedition in the Himalaya.

A fake pilgrim and mysterious pills

Gansser and his three companions crossed the border into Tibet at Mangshang La. Gansser disguised himself as a Buddhist pilgrim. At the time, it was forbidden to collect samples from the area, which is considered sacred land.

“I was able to hide a lot of things under my red sheepskin caftan cloak, such as a geologist’s hammer, camera, sketchbooks, and a compass,” Gansser wrote.

Augusto Gansser disguised as a Buddhist monk. Photo: Wikipedia

Although Gansser claimed to be a “pilgrim from the most distant regions”, the lamas realized that he was not a real monk. Nevertheless, he was able to enter. He was even welcomed by the Dalai Lama, who “[gave] me a bag of small pills to rid me of all possible bad luck,” Gansser later recounted.

Api Main and Nampa

In the spring of 1953, mountaineer William Hutchison Murray arrived in the Api and Nampa area with two companions, Bentley Beetham and John Baird Tyson. Murray had been deputy leader to Eric Shipton on the Everest Reconnaissance Expedition in 1951. But he didn’t acclimatize well and he was not included on the 1953 Everest team.

Beetham was an ornithologist and photographer as well as a mountaineer. A good climber, he had been a member of the 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition, during which Irvine and Mallory perished. Beetham did not summit because he suffered from dysentery and sciatica.

The third member, Tyson, was a mountaineer and school teacher who mapped out previously unexplored areas of the Himalaya. In 1952, he led the first Oxford University Scientific Expedition there, and he maintained a link with Nepal throughout his life.

John Baird Tyson. Photo: The Times

The trio climbed a virgin peak in Yoka Pahar and scouted Api Main but ultimately didn’t attempt to climb it. Murray approached Nampa too but likewise did not try the peak.

An attempt on Api Main and fatalities in 1954

Api Main (7,132m) stands out for its enormous prominence: It rises more than 3,300m above its base. After the exploratory expedition by the British, an Italian team made an attempt in the spring of 1954.

Under the leadership of Piero Ghiglione, the team of five (four Italians and one Nepali) tried to climb the south face. They did not get higher than 5,850m. Then they changed routes and tried the northwest face and ridge, reaching 7,100m, barely 30m from the top.

But the trip proved a disaster. One climber died from acute mountain sickness, another went missing, and a third had a fatal fall from a bridge.

West Seti Gorge, on the traditional trade and pilgrimage route into Tibet. Photo: Ulrich Lachenmair

First ascent of Api Main

In mountaineering, it’s said that if you find a strange or little-known peak and look for information about its first ascent, you will likely discover that a Japanese party first did it.

The first ascent of Api Main proceeded via the 1954 Italian route. On May 10, 1960, Gyaltsen Norbu Sherpa and Katsutoshi Hirabayashi of Japan reached the summit. The next day, Motoh Terasaka and Yasusuke Tsuda also managed to top out. From its summit, there are spectacular views over India’s Nanda Devi (7,817m).

Api Main has seen only 19 expeditions and 23 successful ascents. The last was in October 2015, by Kazuya Hiraide, Takuya Mitoro, and Kenro Nakajima of Japan. A Czech team planned to try it in 2019, but they couldn’t even reach base camp because of landslides on the trail.

Sunrise on the surrounding mountains during a climb on the southwest face of Saipal (7,030m). Photo: Arcteryx

Saipal (7,030m)

In autumn 1953, Austrian Herbert Tichy and Pasang Dawa Sherpa reached the Saipal area on the other side of the Seti River. There, they climbed five different virgin peaks between 5,000 and 6,000m. Several of those have either not been attempted since or have seen very little climbing. Eventually, Tichy’s party ran out of time and supplies and was unable to attempt Saipal.

A few months later, in the spring of 1954, another Austrian group wanted to climb Saipal. Rudolf Jonas wanted to climb a mountain west of Saipal, called Firnkopf (6,730m). From the top of Firnkopf, they planned to reach Saipal’s west ridge.

Everything was going well until they reached 6,300m on May 29, 1954. One of the climbers, 29-year-old Karl Reiss, began to feel unwell. Two days later, Reiss passed away from pneumonia, and the group canceled the climb.

The first ascent of Saipal

On September 27, 1963, the Doshisha Himalayan Expedition team arrived at Saipal Base Camp. Led by Kanji Kojima, the group consisted of six Japanese climbers and Pasang Phutar, a Sherpa with extensive experience.

They chose to try the south ridge. Between Camp 1 and Camp 2, there was a very steep ice wall followed by a difficult rock ridge.

The northeast ridge of Saipal. The main summit is in the background. Photo: Paulo Grobel

On October 21, 1963, Katsutoshi Hirabayashi and Pasang Phutar reached the top of Saipal. Hirabayashi later summited Api Main as well.

After the successful first ascent of Saipal, the team built a bonfire at Base Camp and spent the night singing and celebrating. “We got drunk not only with brandy but also on our success,” Kojima recalled.

Today, only 18 people have summited the main peak of Saipal. The last was in 1998, by two Japanese climbers.

Jethi Bahurani 6,850m. It has only one official ascent, by three Japanese climbers in 1978. Photo: Kathmandu Guide

Nampa

Although Nampa (6,729m) had already caught the eye of W.H. Murray in 1953, the first real attempt was only in the autumn of 1970. A British team from Manchester attempted to climb it via the south face and west ridge, under the leadership of John Allen. They finally stopped at 6,250m because a member of the group was suffering from AMS, and the weather had deteriorated.

A Japanese team chose that same route in the spring of 1972. Team leader Seigo Matsushima consulted with Allen and decided to climb the British route because the 3,000m south face was very steep and the east ridge had difficult icefalls. But the west ridge was not easy, either.

Fukutoshi Kimura and Susumu Takahashi made the only summit push. On May 4, 1972, the pair bivouacked at 6,500m in very dangerous, icy conditions. Finally, they managed to reach the summit on May 5 at 12:30 pm. After spending an hour at the top, Kimura and Takahashi began to descend.

The fatal fall

Kimura led the descent. The two climbers were on blue ice, just below the summit, 200m from where they had bivouacked the night before.

Then Takahashi’s ice pick came off the hard ice. He slipped and fell 2,000m into an inaccessible abyss. Someone said that his fall was as if he “had been thrown out of an airplane”. Kimura managed to make it down alive.

Since 1972, only two other expeditions have gone to Nampa, the most recent in 1996.

Jethi Bahurani, photographed by the American guide, skier, and climber Luke Smithwick.

Jethi Bahurani

Even less frequented is Jethi Bahurani (6,850m). It has seen just three expeditions in all. The first attempt was in the autumn of 1972 by a Japanese team via the north ridge. At 6,150m, after the death of a Sherpa and a fierce storm, they aborted.

British climbers tried the south ridge in the spring of 1974 but also left without a summit. Their expedition retreated from 6,250m in deep snow and bad weather.

Finally, Japanese climbers Kazuo Mitsui, Hideki Yoshida, and Nobuhito Morota managed to climb Jethi Bahurani on April 27, 1978, via the very steep east ridge. The group had permission for Nampa South, but Nepal’s authorities said that they did not have a permit for Jethi Bahurani. Although this first ascent was accepted, Nepal banned the leader of the expedition, Kazuhiko Yamada, from climbing in the country for five years.

Bobaye. Photo: Roger Nix

The Three Peaks Expedition

In autumn 1996, the Slovenian Alpine Association organized the Three Peaks Expedition to Api Main, Nampa, and the unclimbed Bobaye. Led by Roman Robas, the group included Dr. Frenk Srakar, Dusan Debelak, Jernej Grudnik, Tomaz Humar, Matic Jost, Peter Meznar, Janko Meglic, Marko Prezelj, Bostjan Slatensek, Tomaz Zerovnik, and Andrej Stremfelj. In addition, Mingma Tensing Sherpa (sirdar), Pasang Kaji Sherpa (cook), Ang Kami Sherpa, Sandem Sherpa, Tashi Tubdu Sherpa, liaison officer Dwarika Prasad Bhattarai, and more than 80 porters accompanied the Slovenian group.

The team established a common base camp at 3,650m, below the three mountains on a strawberry field. Then the Slovenians divided into small groups for the climbs. They climbed in pure alpine style.

Three new routes

The Slovenians climbed three new routes. On November 3, 1996, Matija Jost and Peter Meznar completed the second ascent of Nampa, via a new line on its south face.

On November 4, 1996, Dusan Debelak and Janko Meglic summited Api Main, also via a new route, this time on the southeast face.

And then there was Tomaz Humar. When we talk about Humar, we remember his incredible climbs, mostly solitary, with a high level of commitment. There was also his unpredictable character, together with his technical skills, that pushed him to achieve great feats, including Ganesh V, Annapurna, Ama Dablam, Dhaulagiri, and many, many more. We remember his last ascent where he lost his life, on the south face of Langtang Lirung. During his career, he made more than 1,500 climbs, more than 70 of them on new routes.

However, the media has said little about his first solo climb, on Bobaye in the fall of 1996.

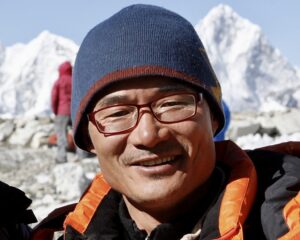

Tomaz Humar. Photo: Wikipedia

While his companions were on the other two peaks, Humar climbed Bobaye.

“I had never before felt as alone as I did on October 30, while I packed my 30-kilo backpack. I needed someone who would say something I could take with me,” Humar later said about the start of his climb.

View from Bobaye. Photo: Tomaz Humar

The first ascent of Bobaye

Humar began on November 1, 1996, at 2 am. First, he had to cross a dangerous glacier in deep snow, full of hidden crevasses. Then he started up the west face, into a diagonal couloir of 80 degrees, bombarded by the ice of a frozen waterfall.

Next, he traversed toward the northwest ridge. The terrain was unknown, and Humar made slow progress. He had to bivouac on the face at 5,500m, in an ice cave under threatening seracs. After the bivouac, he reached the northwest ridge and crossed over onto the northwest face. Through a rock band covered by thin ice at 6,500m and over a saddle, he reached the summit of Bobaye on November 2, 1996, at 1 pm. Much of his route was on terrain between 60 and 90 degrees.

He descended via a new route too, a much more direct way via the west pillar and the west face. He dedicated the up-route to his wife and called it “Golden Heart”. The down-route he named for a lost climbing partner and friend, Vanja Furlan.

There have been no further expeditions or climbs on Bobaye since Humar’s first ascent.

Tomaz Humar died on the south face of Langtang Lirung on November 10, 2009. Photo: John C. Sill