Exploration stories are rife with extreme deprivation, both physical and mental. “Sexually and socially, the polar explorer must make up his mind to be starved,” wrote British polar explorer Apsley Cherry-Garrard, recalling the isolation he experienced in the Antarctic.

But few explorers endured what Ejnar Mikkelsen and Iver Iversen did. These two Danes, abandoned by their ship, spent two winters in a tiny hut in northern Greenland. They emerged unrecognizable.

In 1906, a Danish expedition led by Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen set out to explore the northeast coast of Greenland and survey over six degrees of latitude. Ejnar Mikkelsen was not a member of the expedition, but like many others interested in Arctic exploration, he was waiting for news of the ambitious expedition.

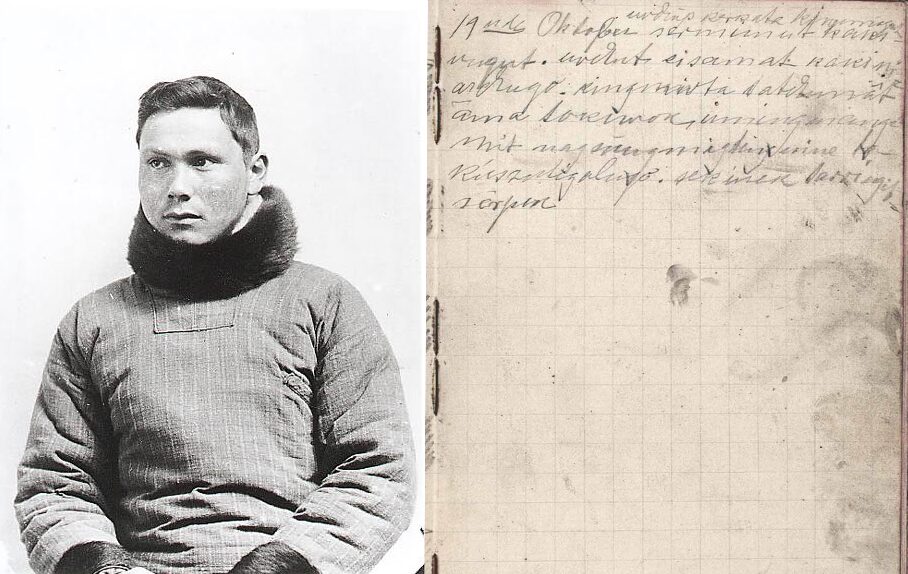

In 1908, Mikkelsen and the rest of the world learned that Mylius-Erichsen and two companions, Lieutenant Hoeg Hagen and an Inuit man called Jorgen Bronlund, had all perished. Bronlund, the final survivor, had reached an established depot before he died. On his body, he carried an account of the party’s struggles. However, most of the expedition’s journals and observations had been left behind and were missing.

Ejnar Mikkelsen was determined to retrieve them and preserve the work that the three men had died to undertake.

Danish explorer Mylius-Erichsen’s ship ‘Danmark’ off the coast of Greenland in 1907. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Alabama sets sail

Mikkelsen had been at sea since he was 14 and already had several polar expeditions under his belt when he began planning to set off after Erichsen. Ambitious and indefatigable, as a teenager he had hiked over 500 kilometers to Gothenburg to meet with S.A. Andree. who was about to launch a balloon expedition to the North Pole. Mikkelsen begged to be taken on the ill-fated mission, but luckily for him, Andree said no. All perished.

Mikkelsen did manage to join an expedition a few years later, signing onto Amdrup’s

expedition to East Greenland. Immediately after returning in 1901, he set out again on the Baldwin-Ziegler expedition to Russia’s Frans Josef Land. Then, while Erichsen and his men were dying in Greenland, Mikkelsen led an Anglo-American polar expedition across the frozen Beaufort Sea.

His bona fides had become ironclad, and so when he applied to lead an expedition to look for the remains of the Erichsen party, he received widespread support. Funded half by the Danish government and half by private subscription, he bought a small sloop called the Alabama in 1909.

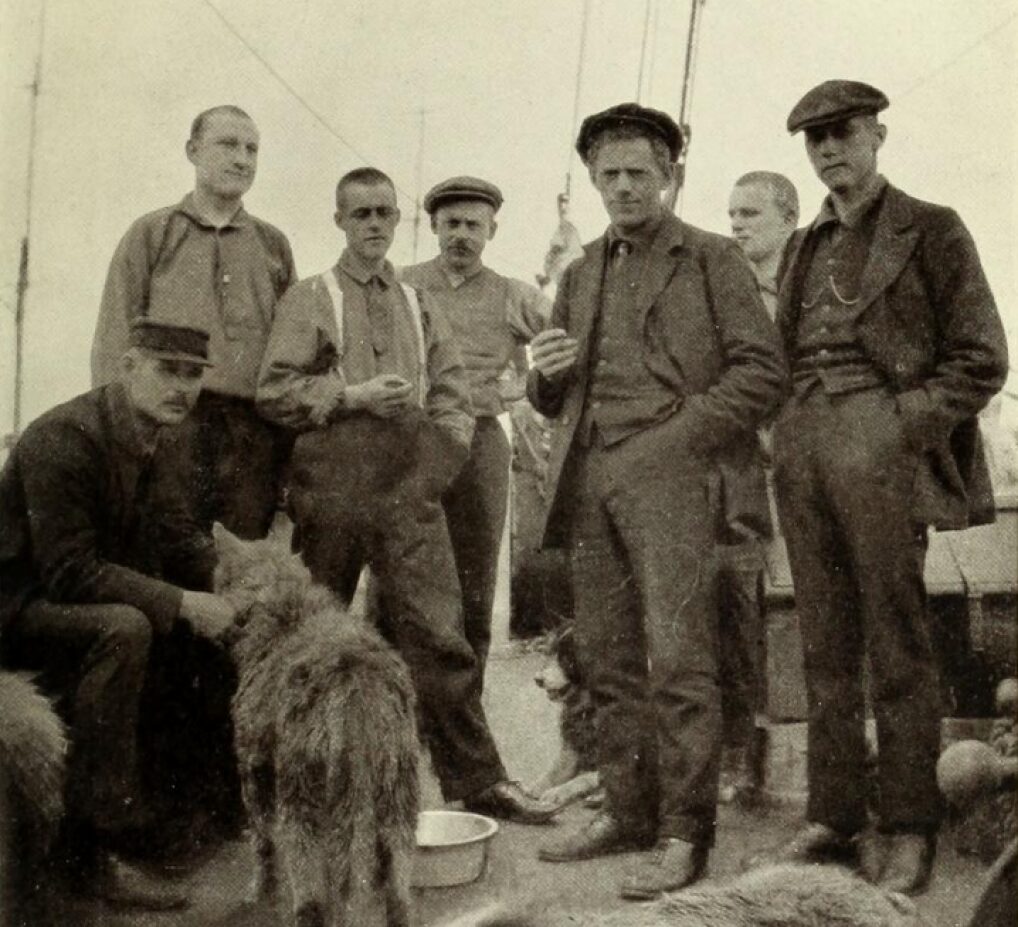

Not intended for the ice, the Alabama was rebuilt and retrofitted with a 15-horsepower motor, then loaded with 18 months of supplies. Besides Mikkelsen, the small crew consisted of only six others: Royal Navy Lieutenant Wilhelm Laub, Infantry Lieutenant C. H. Jorgensen, carpenter Carl Unger, mechanic Aangaard, and mates Hans Olsen and Georg Paulsen.

They set sail on June 20, 1909.

Members of Mikkelsen’s expedition. Left to right: C.H. Jorgensen, Carl Unger, Hans Olsen, Aagaard, Ejnar Mikkelsen, Georg Poulsen, and Wilhelm Laub. Photo: Ejnar Mikkelsen, 1913

One hardship after another

Things began poorly. The weather was poor, and the dogs were sick. One by one, they were dying, and when Mikkelsen managed to find a veterinarian, his advice was that the animals were doomed. Reluctantly, the men put down the remaining ill dogs.

Luckily, Mikkelsen was friendly with the people of nearby Ammassalik Island, whom he had met on the Amdrup expedition. He bought 47 healthy dogs from them, but the stop delayed the expedition’s arrival in Iceland.

Meanwhile, the mechanic Aagaard had “fallen sick,” as Mikkelsen delicately put it. In reality, he was struggling with an alcohol addiction, which made him distinctly unsuited for the journey. They dropped him off at a small Icelandic village, then telegraphed the nearby naval vessel, Islands Folk. Did they have any volunteers who knew their way around an engine?

They sent over their eager assistant engineer, a young man named Iver Iversen. His appointment was so short notice that he had no chance to make arrangements or bid his loved ones goodbye.

Staffing issues resolved, the Alabama said farewell to the Islands Folk, and with it, the world they knew. They forged ahead alone into the cold northern waters.

Bad weather continued to oppress them. By late August, the Alabama was trapped in the ice off Shannon Island, about 300km from where Erichsen’s party had wintered.

The ‘Alabama’ at anchor in summer 1909. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Miserable work

Before winter truly set in, Mikkelsen set off on an initial exploratory journey with Iversen and Jorgensen. Autumn sledding, he admitted, was miserable work, and they lost several dogs. However, they succeeded in reaching their goal, the depot on Lambert’s Land where Jorgen Bronlund had died.

His body was still there, preserved by the Arctic cold, and they searched it for clues. All the records he had carried had already been collected, so they buried him solemnly and moved on. The small party split up to explore the area, searching for Erichsen’s last camp without success.

With winter closing in and supplies low, they turned around. After a difficult journey — they ran out of food and fuel and lost many dogs — they rejoined the Alabama crew at its winter quarters on Shannon Island.

The crew passed the winter as well as could be expected, managing to keep warm and fed and not poisoned by anything. This is the height of luxury on a polar expedition. Jorgensen, however, had been very badly frostbitten, and by spring, he still wasn’t fit to sled.

Though his second-in-command was out of commission, Mikkelsen pushed on, sending depot-laying parties in early spring and preparing sledding equipment. Once ready, Mikkelsen set off. Lieutenant Laub, Olsen, and Poulson would accompany him for the first leg, with only Iversen continuing on with him.

The pair had no idea that they were beginning a nearly three-year-long ordeal.

Jorgen Bronlund, left, was an experienced polar traveler. The son of a Greenlandic Inuit hunter and childhood friend of explorer Knud Rasmussen, he acted as an expert interpreter for Mylius-Erichsen. Left, the final page of his diary, written in Greenlandic. Photo: Wikipedia/Det Kongelige Bibliotek

On the trail of Mylius-Erichsen

The journey was slow going. The weather was as bad as ever, and they carried so much weight in supplies and had so few healthy dogs left that they had to go in stages. For every kilometer of progress, they had to travel three kilometers. Though they hadn’t made it as far as they’d hoped, Iversen and Mikkelsen said goodbye to their three companions on April 10. They continued on, while the other three returned to the ship.

Mikkelsen and Iversen prepare to set out on April 10. Photo: Ejnar Mikkelsen, 1913

Knowing that they may not rejoin the Alabama before she was freed from the ice and made her escape, Mikkelsen wrote to his former captain, Amdrup. If they failed to return on the Alabama, he wrote, there was no cause for concern. He and Iversen would find a passing sealing ship to take them home. He also wrote that there was no reason to send a relief mission. Any attempt to find them would be like looking for a needle in a haystack.

Iversen and Mikkelsen continued to struggle northward. After crossing a stretch of inland ice riddled with deadly crevasses and impassible cliffs, the two reached Danmark Fiord, down several dogs. There, they began to trace the steps of Erichsen’s lost party.

In late May, they found a cairn and the remains of a camp, with a note that Erichsen had left. It was heartbreakingly sanguine: They had starved and struggled but had recently found game and hoped to reach their ship in six weeks by following the coast.

“Poor fellows,” Iversen exclaimed aloud. “So glad and hopeful here — and then — what they must have gone through before the end!”

A few days later, they reached a second cache and found another message. What was written there would serve as an answer to the mystery of Erichsen’s death. The bodies of Erichsen and Hogan were never found.

The cairn where Mikkelsen and Iversen found the last records of Erichsen’s party. Photo: Ejnar Mikkelsen, 1913

The nonexistent Peary Channel

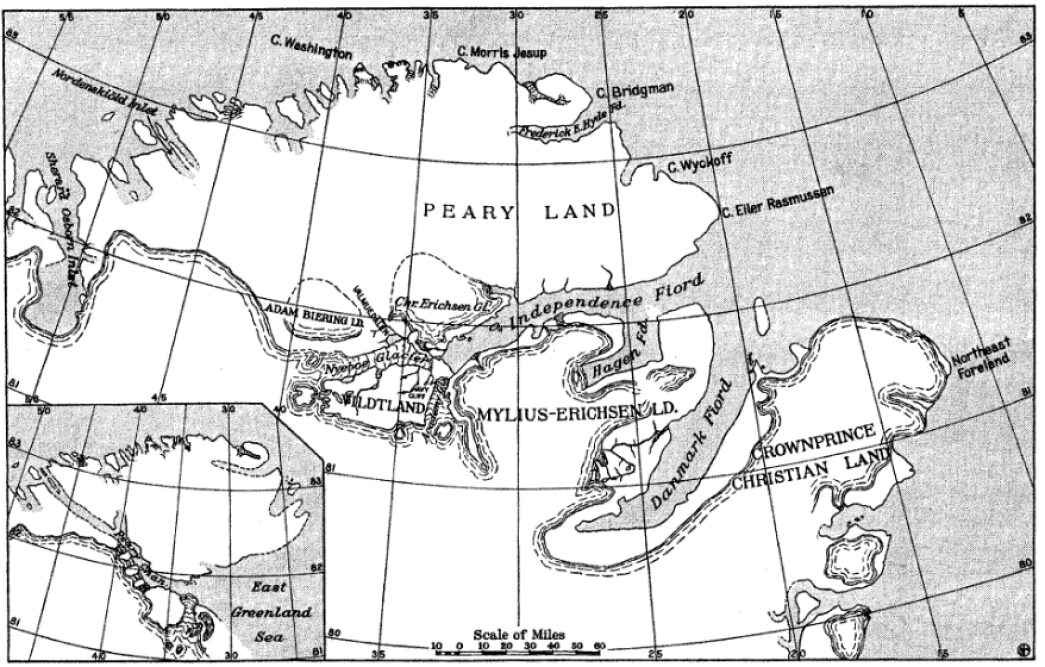

The note harrowingly described the expedition’s struggle, but what struck Mikkelsen most was a geographical revelation: “Peary’s Channel does not exist.”

Robert Peary was an American explorer best known for not discovering the North Pole. On an earlier 1892 expedition to Greenland, he had mapped a long swath of the coast. On this map, he placed a marine channel separating Peary Land from mainland Greenland. According to his account, he had observed the entire channel, and even a number of islands within it, from a vantage point on Navy Cliff. This supposed discovery of the north end of Greenland and land beyond it first made Peary famous.

Nowadays, many historians believe that Peary deliberately lied about his discovery. One of the men accompanying him, a respected explorer named Eivind Astrup, even insisted that Greenland extended far past Navy Cliff. There was no channel. But official support went to the politically savvy Peary. Sadly, Astrup took his own life in 1896, aged only 24, before he could be proven right.

Peary’s observations formed the basis of the maps that both Erichsen and Mikkelsen had used, and both parties had made their plans based on the existence of an open waterway. The waterway, Mikkelsen explained, would have allowed them to reach civilization much more quickly than a journey along the east coast of Greenland. Erichsen’s party had faced the same problem, and it had likely contributed to their deaths.

The expedition’s goal, at least, had now been met. Mikkelsen and Iversen could contemplate the long way home, at least knowing that they had recovered the important discoveries Erichsen, Hogan, and Bronlund had made.

Published in 1916 by the Geographical Review, this diagram compares Peary’s map, insert, with its through channel, and an updated map. Photo: Geographic Review

A desperate dash

The Alabama was over 1,200km away. The season was late. They had only seven exhausted dogs left and almost no food. As the dogs weakened further, Mikkelsen felt his strength ebbing, too.

By early June, he was unable to walk, suffering from aching muscles, swollen joints, and dark purple bruises all over his body. Iversen helped him onto the sled, leaving most of their remaining supplies so that their weak dogs could pull Mikkelsen. Though he was initially reluctant to admit it, scurvy had taken hold.

Iversen remained cheerful, and as they moved south they found game and old depots of food. The vitamin C in the fresh meat helped Mikkelsen, who was soon able to walk. But it was too late for most of the dogs, and they were soon down to three.

That number became two with the death of Girly, Mikkelsen’s favorite dog. Though she had been sick for some time, he was unwilling to put her down like he had others, and she had been riding on the sled. But in the end, they butchered Girly and fed her to the last two dogs. Mikkelsen wrote that he wished he could’ve buried her properly, with a gravestone reading, “Here lies Girly — her little life of faithful and untiring service ended.”

Two pictures of Girly. Mikkelsen’s favorite and leader of his dog team, she was the only dog allowed to sleep in the tent. Photo: Ejnar Mikkelsen, 1913

Abandoned

Iversen also grew weak and sick as they went on. Eventually, they were forced to leave everything– even tents, sleeping bags, and diaries — in a final effort to reach Alabama.

On September 19, they reached her. But what should have been a triumph was a bitter disappointment. She had been wrecked by the ice, and the other five men had gone home on a passing sealer.

The wreck of the ‘Alabama.’ Photo: Ejnar Mikkelsen, 1913

The Alabama Cottage

Their shock was devastating, numbing. Neither swore or even spoke at all. “So confident we were,” Mikkelsen wrote ruefully, “and now so utterly alone and helpless.”

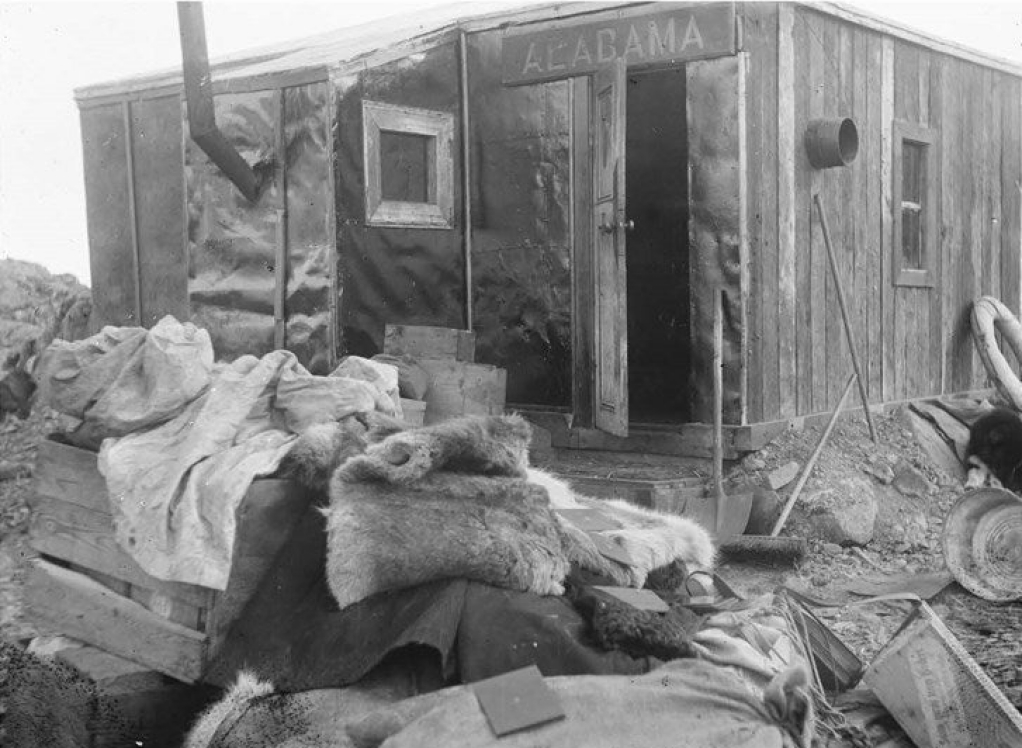

Mikkelsen and Iversen built a small hut out of the wreckage of the lost ship. With the Alabama‘s remaining supplies, they weren’t in immediate danger of starving. The little canvas-covered hut would keep them from freezing.

Without coal, they had to slowly cut up and burn what was left of the ship. Even then, temperatures inside the hut were rarely much above freezing. While Mikkelsen cannibalized the ship for warmth, Iversen took it upon himself to serve as cook. He was not gifted in the arena, and the best that could be said of their diet was that it was enough to live on.

Aside from daily disputes with the neighbors– a family of arctic foxes that stole their scraps — the winter was uneventful.

The Alabama Cottage, where the two men overwintered for two years. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A third winter

As soon as winter broke, they set out on a sledding trip. It wasn’t an attempt at self-rescue but a trip to retrieve their log books, left during their desperate push to regain the Alabama.

A polar bear had broken into their depot and eaten Mikkelsen’s diary, but most of the log books, with their vital scientific discoveries, were unmolested.

They returned to the Alabama Cottage, confident that a ship would sail in to retrieve them in less than six weeks. The pair even adopted six baby hares, setting them up in a box in their hut. Caring for and playing with them was a welcome distraction from the waiting.

By mid-August, however, no ship had come. They had to face the dread prospect of spending another year in the Arctic. Worst of all, they were running out of fuel. They spent the autumn making a series of frantic trips back and forth from an American depot, where they discovered that a ship had stopped by, missing them by only 25km.

Once they settled in, boredom was again all-consuming. When Mikkelsen got a toothache, he was initially pleased because at least it was something new. They spent hours every day examining a book of postcards and coming up with backstories for the people pictured in them. They also adopted a “house-fox,” and named him Prut.

The pair launched escape attempts by boat and by sled, but both proved impossible. Waiting for rescue while trying to keep themselves sane was all they could do.

The ‘Alabama Cottage’ while Iversen and Mikkelsen were living in it. Photo: Ejnar Mikkelsen, 1913

Unrecognizable

Early on the morning of July 19, 1912, Mikkelsen woke up to see Iversen, half-dressed, running across the room to throw open the cabin door. Mikkelsen looked on in confusion as Iversen yelled, “Good morning!”

Then he realized what it meant — after 28 months of struggle and waiting, a ship had found them. The small Norwegian whaler soon put eight men to shore. The crew stared at the two explorers in shock. The steward, thinking they were dangerous lunatics, even darted back for the ship in fear.

Indeed, after more than two years in the wilderness, Mikkelsen and Iversen were a battered and wild-looking sight. But after the initial shock, the crew welcomed the pair aboard.

The captain, Paul Lillenaes, patiently answered all their questions about what they had missed during their three-year absence. Their king had died. Newspapers speculated on whether they were alive. When they set foot in Aalesund, Norway, a journalist was one of the first to greet them.

Mikkelsen and Iversen at a reception celebrating their return. Photo: Det Kongelige Bibliotek/National Library of Denmark

Mikkelsen had nothing but praise for Iversen, the last-minute addition who had stood by his side for nearly three years. The engineer had had enough of adventure, though, and settled down, never returning to the Arctic.

Ejnar Mikkelsen, on the other hand, spent the rest of his career traveling back and forth from Greenland. Even after his death, he maintains a strong presence there. Since 2007, a Danish vessel bearing his name has patrolled the waters around Greenland.