The original Mercury space capsule had no window, a hatch with 70 bolts that had to be removed from outside, and zilch for the astronaut to do except endure g-forces, hope nothing went wrong, and throw an “abort” switch on command from mission control if it did.

It was so easy a monkey could do it.

The year was 1960. Two years earlier, seven test pilots known as the “Mercury Seven” had fought through almost two years of experimental training to become the first American in space.

It is understandable if their egos were hurt when NASA decided to send up a monkey first.

Correction: a chimpanzee.

In an event that’s varyingly heralded and maligned, the first hominid in space completed his record-setting flight on Jan. 31, 1961. Ham the Astrochimp blasted off on top of a Mercury-Redstone rocket — a rig that amounted to a chair strapped to an eight-story-tall ballistic missile — and punched a hole through the atmosphere.

Ham survived a 250-kilometer-high Mach 7 flight that spiraled out of its planned path and almost killed him. At three-and-a-half years old, he became an incidental hero while still technically an infant.

Three months later, astronaut Alan Shepard became the first U.S. astronaut in space. NASA largely assuaged his and his cohort’s complaints in the years to come. All seven Mercury astronauts made landmark flights as the American space program decisively eclipsed the rival Soviets’.

Ham, meanwhile, never flew again. In fact, according to virtually all accounts, he refused to.

Though the ape was “grinning” when recovery crews rescued him from a sinking Mercury capsule and brought him aboard the U.S.S. Donner, all may not have been well. When handlers later brought him near the “couch” he sat in for his 16.5 minutes in space, he recoiled from it.

In 1983, Ham died from liver failure at a North Carolina zoo at around 26 years old. The Astrochimp’s remains now lie in a commemorative grave at the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico.

But what good is a Hall of Fame honor to a chimp?

It’s been 60 years since NASA closed the books on Project Mercury. Now, space historians, animal advocates, and even philosophers have all spun Ham’s story into a complex fabric that unites humans with our closest living ancestors — but also highlights a mutual isolation.

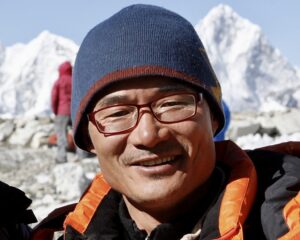

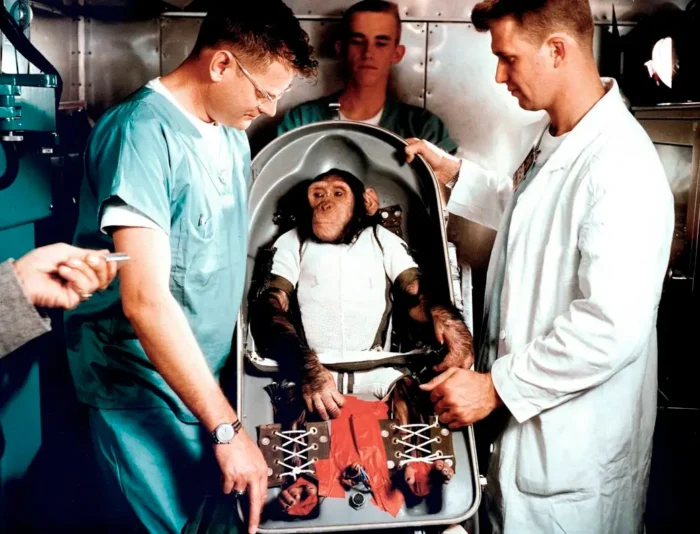

Ham with his lead handler at Holloman Aerospace Medical Center, Edward C. Dittmer, Sr. Photo: International Space Hall of Fame

Number 65

Ham was born in approximately 1957 in what was then French Cameroon, West Africa. Captured by trappers, he soon ended up at a Florida tourist attraction called the Miami Rare Bird Farm. In 1959, the U.S. Air Force purchased the young chimp for $457 and transferred him to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.

The facility spelled out Ham’s name in acronym — Holloman Aerospace Medical Center — but at first, he was just a number.

The U.S. military had been busy acquiring chimps to support testing for the space program. Urgency had run high since October 4, 1957, when the U.S.S.R. struck fear into the free world by launching a microwave-sized, largely inert object.

Sputnik 1 had achieved an elliptical low-Earth orbit, which it proved by transmitting basic, beeping radio signals around the planet.

It’s hard to overstate the primitivity of early space engineering. At the start of the Mercury program, engineers were still trying to figure out if humans could perform tasks in orbital flight as mundane as operating levers. It’s one of the factors that make those early achievements so astonishing.

Enter Number 65 and the rest of Project Mercury’s test chimpanzees.

Ham shortly before his historic flight. Photo: NASA

When NASA personnel selected him and 39 other chimps for aptitude testing — which was virtually identical to the human astronauts’ training — the only living creature in space had been Laika, the Soviet dog.

Laika, a stray plucked from the Moscow streets, died in orbit on a 1957 mission that became infamous for animal rights abuse even at the time. In a cruel turn of early space travel, Sputnik engineers shot the female stray into space with one meal and the expectation that she would run out of oxygen and die in seven days. (The flight went awry and she likely died within hours.)

NASA officials claimed that the U.S., in contrast, chose chimpanzee pilots because they wanted the animals to survive their flights from liftoff to capsule recovery and work while they were on board.

They resembled astronauts, could potentially perform similar tasks in the capsule, and were docile, NASA said.

NASA manuals referenced in the 1998 book, This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury, read:

Intelligent and normally docile, the chimpanzee is a primate of sufficient size and sapience to provide a reasonable facsimile of human behavior. Its average response time to a given physical stimulus is .7 of a second, compared with man’s average .5 second. Having the same organ placement and internal suspension as man, plus a long medical research background, the chimpanzee chosen to ride the Redstone and perform a lever-pulling chore throughout the mission should not only test out the life-support systems but prove that levers could be pulled during launch, weightlessness, and reentry.

Flight school

Ham the Astrochimp’s training followed B.F. Skinner’s conditioning theory: rewards for the correct response, corporal punishment for the wrong one.

Project Mercury handlers strapped chimps into simple chairs, facing a panel fitted with colored lights and levers. According to the National Air and Space Museum, they earned banana pellets if they responded to the right light-and-sound cue by activating the right lever. If not, they received electrical shocks on the soles of their feet.

They endured rocket sled launches, sat in isolation training, and performed intelligence tests. They also underwent g-force testing in a massive centrifuge at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, just like the astronauts. Incessant medical checkups and monitoring accompanied the regimen.

Edward C. Dittmer, Sr., a World War II veteran and non-commissioned laboratory officer, acted as Ham’s lead trainer at Holloman. Later, he repeatedly praised the chimp’s trainability and sometimes humanized him.

Dittmer said, according to the Space Hall of Fame:

“…I think…I know he liked me. I’d hold him, and he was just like a little kid. He’d put his arm around me and he’d play, you know. He was a well-tempered chimp.”

Tom Wolfe, author of the celebrated Mercury Project chronicle The Right Stuff, wrote that the relative peace was hard-won. Before “rebellion proved to be a dead end” for the chimps, he wrote:

The beasts tried everything they could think of to escape. They snapped, snarled, bit, thrashed at the straps, and made runs for it. Or they bided their time and used their heads. They would go along with a training task, seeming to cooperate, until the white smoker seemed to let his guard down — then they’d make a break for it. But the resistance and the wiles were of no avail. All they got for their struggles was more zaps.

Engineers at Holloman culled the entry class of 40 primates down to 18. Six finalists, including Ham, moved on to Cape Canaveral, Florida for final testing.

Starting on January 2, 1961, 29 separate tests stood between the chimps and the planned suborbital flight. Three weeks later, NASA wrote, the tests “had made each of the six chimps a bored but well-fed expert at the job of lever-pulling.”

When the electrical shocks and the banana pellets abated, Ham emerged at the top of the pile along with a female alternate.

“The competition was fierce, but one of the males was exceptionally frisky and in

good humor” in the days leading up to the space flight, NASA wrote.

Ham and his alternate went on a “low-residue” diet 19 hours before liftoff and awaited circumstances they couldn’t possibly anticipate.

Rocket rides

Until flight day, Jan. 31, 1961, the United States space program had produced discouraging results.

Throughout the ’50s, Jupiter and Atlas rockets veered off course and exploded spectacularly, on and off the tortured Cape Canaveral launchpad.

The Redstone proved more reliable in early tests but was still a beast of a machine.

It was essentially a 10-meter aluminum can of liquid oxygen and ethyl alcohol on top of a gaudy combustion engine. First designed as a surface-to-surface ballistic missile with an 800km range, it generated 35,380kg of thrust and tore through the sky at 9,400 kph, or Mach 7.5.

The Mercury capsule acted as its nosecone, and the astronaut — or astrochimp — held on for the ride.

The first Mercury-Redstone launch attempt, MR-1, took place on Nov. 21, 1960 — just over two months before Ham’s flight. It was an unmanned test, and despite the rocket’s menacing power, anyone or anything strapped into the capsule that day would have experienced almost nothing but a meek trip from the top of the rocket back to the ground.

When NASA hit the ignition on MR-1, the rig fumed briefly, climbed a few centimeters off the launch pad, and settled back down. Then, comically, an electrical chain reaction caused the escape tower to blast off and deployed the still-attached capsule’s drogue (or safety) parachute.

The so-called “four-inch flight” drew public ridicule to Project Mercury, along with a little levity. But it also introduced glaring safety concerns. If Ham or any astronaut had been on board, they would have been trapped on top of a teetering, 25-meter-tall live bomb.

The failure also delayed planned tests of the recovery system. This was a critical piece of the Mercury program, in part because capsules would touch down in the ocean off the Florida coast. Recovering a capsule was an all-hands-on-deck situation: a plethora of aircraft and ships were involved. Failure meant the capsule could sink, dooming its occupant to drown.

By the time Ham and his alternate astrochimp made their final trip out to the launch pad for MR-2, only one Mercury-Redstone test (MR-1A) had succeeded.

Malfunctions and setbacks delayed Ham’s January 31 flight almost to the breaking point. And when the rocket finally did lift off, it put him through conditions more extreme than anyone expected.

‘Ham’ in a can

Accounts report Ham’s condition as calm on the morning of the launch. His handlers secured him in his couch, then trolleyed him toward the Redstone.

This New Ocean renders the moment stirringly, if oddly:

“There, an hour and a half before the scheduled launch time, the chimpanzee named ‘Ham,’ still active and spirited although encased in his biopack, boarded the elevator to meet his destiny.”

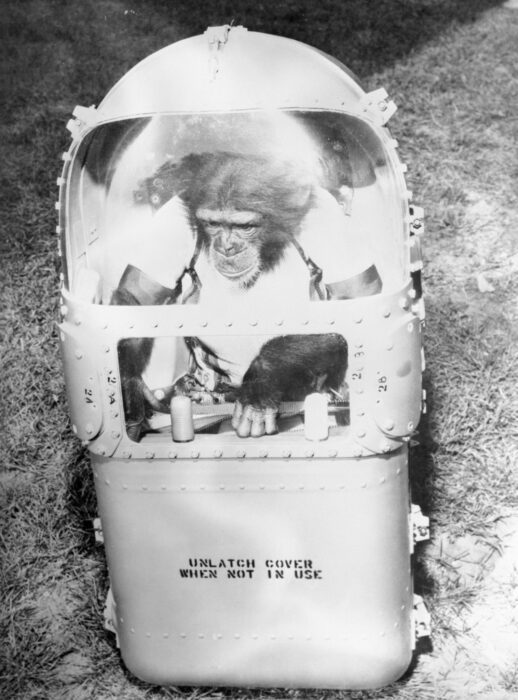

Ham inside his ‘couch.’ Photo: Creative Commons

MR-2 was scheduled for liftoff before noon because mission control didn’t want to risk a night recovery. According to NASA, the hours-long countdown and final check process went as planned until about 7:45 am. That’s when a “tiny but important” inverter in the automatic control system started overheating.

Nevertheless, technicians loaded Ham into the capsule at 7:53 am and bolted down the heavy hatch for liftoff.

Hours of delays followed as mission control tried to fix the inverter. Chaos beset the launchpad, too, as an elevator got stuck, too many people took too long to clear the pad area, checks of the environmental control system ran 20 minutes too long, and flaps on the rocket’s booster tail jammed.

At 11:40, This New Ocean’s authors wrote, “it was decided that now or never was the time to go today.”

Five minutes before noon, controllers hit the red button, and Ham shot skyward.

Seconds into the flight, the Mercury-Redstone started to pitch upward. A launch angle just one degree steeper could significantly alter the flight plan. Speed, duration, recovery point, and g-forces all changed dramatically.

According to NASA, the high angle slammed Ham with a maximum g-force of 14.7 (making his body weigh 243 kg). He experienced 58,000kg of thrust for one unplanned second, and his 8,200 kph top speed was about 1,000 kph faster than planned.

Ham’s flight hit its apex at 253km — about 150km above the rough threshold between Earth and space. He was weightless for 6.6 minutes, according to NASA, during a flight that lasted two minutes longer than expected.

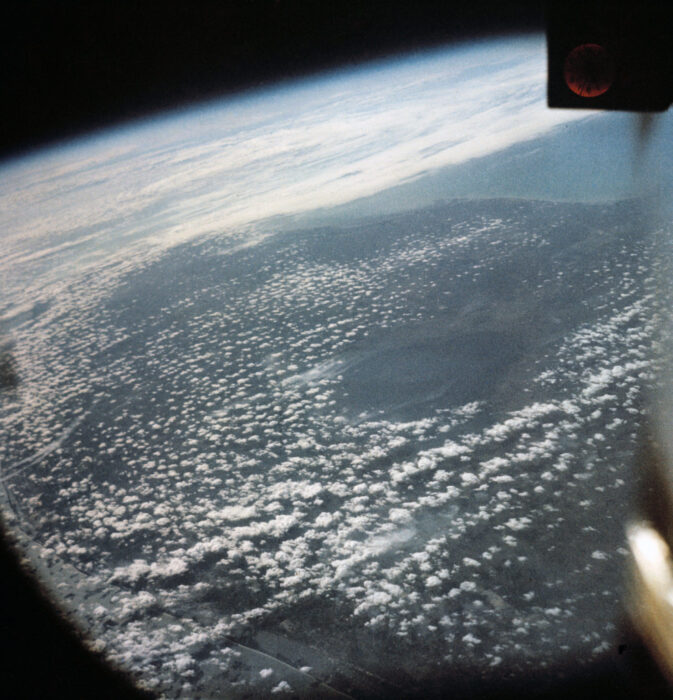

View from MR-2, Ham’s spacecraft, at the apex of his flight. Photo: NASA

At the capsule’s highest point, NASA knew Ham was going to come down farther away — much farther away — than mission control hoped.

“At its zenith, Ham’s spacecraft was already 77km farther downrange than programmed,” NASA calculated. He landed over 200km away from his target landing site.

Ham still wasn’t out of the woods. Cabin pressure had plummeted at one point during the flight. NASA later traced the problem to a spring-loaded valve that had unexpectedly popped open from vibrations.

This breech, and a rough landing due to an overcooked reentry, almost spelled the end for Ham.

When the capsule splashed down at 12:12 pm, it turned upside down and started sinking. The closest rescue was a destroyer stationed almost 100km away.

When the helicopters arrived on the scene, they found the spacecraft on its side, taking on water, and submerging. Wave action after impact had apparently punished the capsule and its occupant severely. The beryllium heatshield upon impact had skipped on the water and bounced against the capsule bottom, punching two holes in the titanium pressure bulkhead. After the craft capsized, the open cabin pressure relief valve let still more sea water enter the capsule.

Pilots finally recovered the spacecraft around 3 pm, filled with about 360kg of water.

On board the U.S.S. Donner post-flight. Photo: Creative Commons

It’s unknown how long it would have taken the capsule to sink, but Gus Grissom almost drowned under similar circumstances on MR-4 six months later. (NASA incorporated an explosive escape hatch into the Mercury design in the interim.)

Through his ordeal, Ham reportedly remained calm and performed admirably — pulling his levers when prompted to avoid the shocks on the soles of his feet. The punishment program was strenuous, with a clock that reset to schedule a new shock every 15 seconds. If Ham failed to prevent it, he would get a full blast.

(Enos, who became the first chimpanzee to orbit the Earth later that year, endured an especially grim situation. During his three-hour flight, the shock system shorted out and inverted. The five-year-old chimp responded to every prompt perfectly but still received 76 shocks.)

Grounded

Ham never flew again. Despite the “grin” he displayed as he accepted an apple after MR-2, he refused to go near his couch for a photo shoot on a later occasion. Though interpreted as a happy gesture at the time, the grin likely meant something else.

The ‘grin.’ Photo: Creative Commons

The world-famous Jane Goodall assessed it for the 2003 film One Small Step: The Story of the ‘Space Chimps.’

“Actually, that is the most extreme fear that I’ve ever seen on any chimpanzee,” she said. It’s now widely thought that when a chimpanzee shows its top teeth during a smile, as Ham did, it’s not a smile — it’s a “fear grimace.”

From the deck of the U.S.S. Donner in 1961, Ham’s story didn’t get brighter. NASA eventually transferred him to the Smithsonian Zoo in Washington, D.C., where he lived alone until 1980. (It’s also widely understood that chimpanzees need companionship to flourish.)

Finally, Ham arrived at the North Carolina Zoological Park in a habitat among several other chimps but died of liver failure three years later. NASA would macerate his corpse for research: separate the flesh from the bones, usually by soaking in room-temperature water. His skeleton showed no signs of stress from his space flight, according to the U.S. National Museum of Health and Medicine. His soft tissue was cremated and transported to his ceremonial grave at the Space Hall of Fame.

Ham’s skeleton. Photo: National Museum of Health and Medicine

It’s impossible to quantify the stimulation Ham incurred during his Project Mercury experience — or during the rest of his life. Shock treatment on monkeys started PETA, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has repeatedly tried to ban it on humans. The human body can only endure the g-forces Ham survived for about a minute.

“Being unable to debrief his handlers, Ham alone knew at this time how grueling his flight had been,” said Robert F. Wallace, an information officer onboard the U.S.S. Donner when Ham landed.

There’s an aviator slang phrase for a pilot with no control over his ship. To a pilot, “SPAM in a can” means exactly what it sounds like: your aircraft is the can, and you’re the SPAM.

Ham’s name is an acronym, sure, but how hard is it to make the SPAM leap?

“[Ham] still would have been nursing at age 3 ½, dependent on his mother for survival,” Save the Chimps points out. “It is hard to imagine a human toddler performing as well as Ham in this challenging task. It speaks to his character, intelligence, and bravery.”

Ham’s involuntary contribution helped re-orient the space race in favor of the U.S., which NASA acknowledged. But if his Project Mercury cohort visited him after he left the program, no record of it exists.

“Ham’s survival, despite a host of harrowing mischances over which he had no control, raised the confidence of the astronauts and the capsule engineers alike,” This New Ocean reads.

Wolfe puts a considerably sharper point on it in his last mention of Ham in The Right Stuff. The public attitude toward human space flight after Ham’s success, he wrote, boiled down to “‘My God, do you mean there are men brave enough to try what the ape has just gone through?'”