An eccentric and artist, Arnold Henry Savage Landor won his way into the late 19th-century courts of east Asia by painting royal portraits. He traveled through India with two Persian cats, surveyed in the Himalaya, and ventured deep into the Amazon.

Neglected today, he was a subject of celebration and suspicion in his own time. He hobnobbed with English high society and sold many volumes of travel writing. He also publicly butted heads with the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society, and feuded with Theodore Roosevelt.

Landor’s painting of prayer flags in the Himalaya. Photo: All photos in this article are taken from Landor’s public domain books unless otherwise stated.

A famous grandfather

Arnold Henry Savage Landor was born in Florence, Italy, in June 1867. His mother was Italian, but his father was the son of Walter Savage Landor, a celebrated English author, poet, and satirist. The family had settled in Florence after a series of libel cases and possible involvement in an attempt to assassinate Napoleon III drove the senior Landor out of English society.

When he was two, the younger Landor fell from a six-meter-high wall and sustained a near-fatal head injury. He survived but with significant brain damage. By his own account, it left him with fainting fits and memory issues. While these mostly faded by adulthood, his difficulty with reading and remembering words led him to focus on visual memory and develop his artistic abilities, instead.

Landor did well in art and in school, but seemed prone to accidents. The first chapters of his autobiography are a litany of falls, carriage crashes, and near-strangulations. By the time he managed to survive to teenage-hood, Landor was studying under a Florentine painter. He showed an early talent for social climbing, courting favor with his teacher’s illustrious clients by producing caricature portraits.

Soon he was in Paris, studying (and according to him, excelling) under contemporary giants in the French art world. In fact, Landor felt he was so gifted that further contact with formal education could only degrade his art. One day in 1888, he set off into the French countryside on foot and didn’t look back.

Arnold Henry Savage Landor was heavily influenced by the legacy of his famous and controversial grandfather, Walter Savage Landor, above. Photo: National Portrait Gallery

Sketching around the world

With paints and pencils and not much more, the young Landor made his way across Normandy, through the Pyrenees into Spain, then Malta, Morocco, and Egypt. He painted scenes from his travels for illustrious clients back in England, including the Duke of Edinburgh, brother of King Edward VII.

But even his successful social climbing couldn’t keep Landor in one place. He soon headed for America, where prestigious letters of recommendation won him many portrait clients, including then-President Benjamin Harrison. Landor also noted that he was disappointed that the Statue of Liberty was not as large as he’d hoped. He had the same complaint about the Sphinx in Egypt.

In August of 1889, he was on the move again, on a ship bound for China. It dropped off Landor in the Japanese port of Yokohama.

Japan had only been opened (semi-forcibly) to the Western world a few decades earlier, and it was a place of mysterious fascination in the West. Gilbert and Sullivan’s Japanese-themed opera The Mikado had opened in 1885 and became a massive hit. It was still running on both sides of the Atlantic when Landor arrived in Japan.

Landor painted dozens of scenes of daily life in Japan, venturing outside the port cities where most Western visitors stopped.

Landor and the Ainu

Landor crisscrossed mainland Japan, sketching everything he saw. He produced 24 paintings in the first week alone. He was most interested in areas with little Western contact. Eventually, he took a boat to Japan’s northern island, Hokkaido. There, he soon met an Englishman, who told him that it was impossible to circumnavigate Hokkaido. Especially for a small, frail figure like Landor.

Of course, he immediately took this as a challenge. He loaded up 300 wooden panels for painting, his paints and brushes, a dozen sketchbooks, and a revolver. He then set off, as he later emphasized, alone and without a tent or provisions.

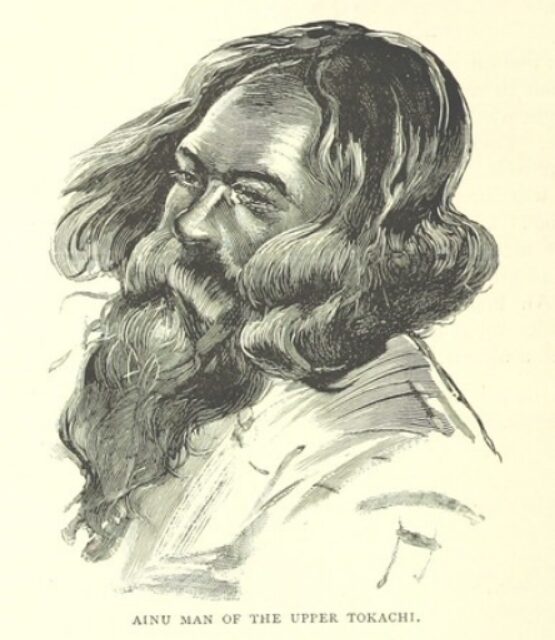

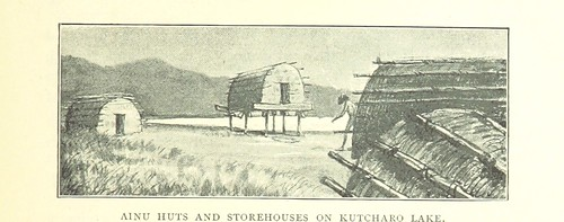

His journey took five months and covered over 6,700km, mostly on horseback. He spent much of his time, and the bulk of his resulting book, with the Ainu people. (The book was flamboyantly titled, Alone with the Hairy Ainu.) The Ainu are an ethnic group indigenous to Hokkaido and parts of nearby islands, subjected to Japanese imperialism and forced assimilation for centuries.

Landor obsessively sketched the Ainu he met, leaving dozens of portraits.

Landor clearly saw himself as something of an anthropologist, recording the daily lives, material culture, spiritual practices, language, and social structures of the Ainu. He explained that when abroad, he follows the natives and “whether they are savage or not, I endeavor to show respect for them and their ideas, and to conform to their customs.”

His cultural relativism only went so far, and the language he uses to write about the Ainu is far from sensitive. Nevertheless, he left us with a detailed record of traditional Ainu life and his experience traveling in late 19th-century Hokkaido.

Landor’s book about his travels in Hokkaido includes dozens of small sketches of scenes, portraits, and Ainu items.

World traveling highlight reel

From Japan, he went to Korea, where he spent much of 1890 traveling, sketching, and observing the people and customs. His prolific public sketches drew significant curiosity. After several weeks in Seoul, he was summoned to the royal court.

With much excitement on all sides, he was asked to paint European-style portraits of two powerful officials, known in English as Prince Min-Yonghwan and Prince Min Yeong-chan. His demand as a portrait artist allowed him to glimpse the private lives and court customs that outsiders rarely witnessed. These unique insights were part of what made his books so successful.

Landor’s portrait of Prince Min-Young-Huan.

After Korea, he went to China, where he met and painted a seascape for Czar Nicholas of Russia. Landor went from China to Australia, where he made a portrait of Sir Henry Morton Stanley, famed explorer of central Africa.

When he finally returned to England, Queen Victoria herself invited him to visit and tell her about his travels. After a brief break to try (and fail) to invent a flying machine, he hit the road again. Ever the opportunist, when he heard of the ongoing Boxer Rebellion in China, he rushed to be there. No sooner had Landor entered the Forbidden City than he was off to Russia.

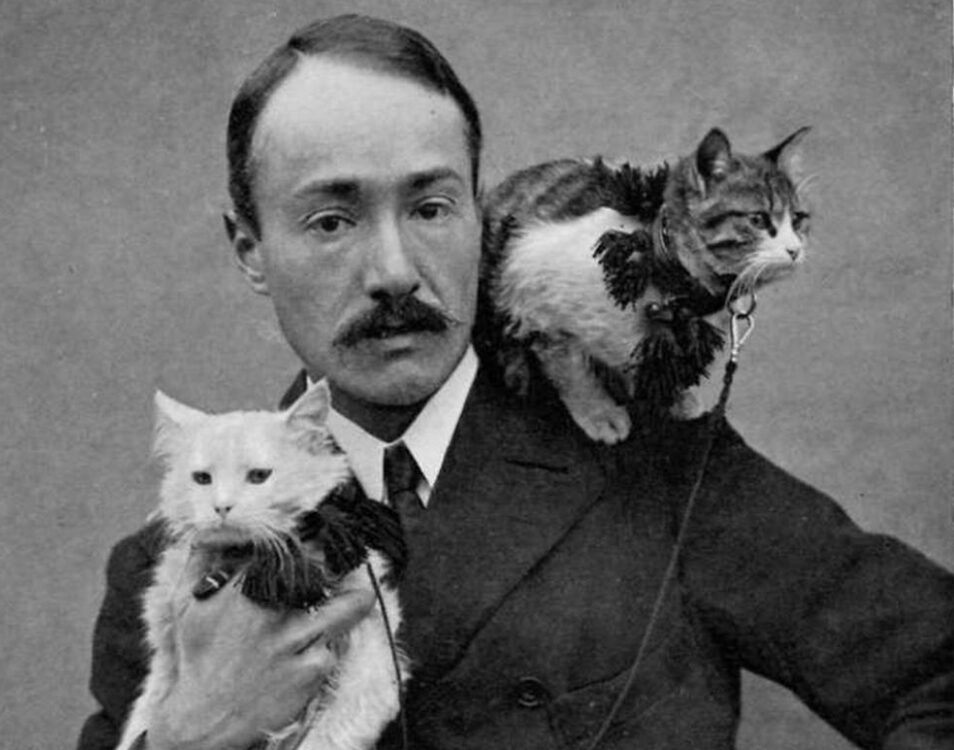

Russia was only the starting point for a long journey all the way down to Calcutta. As usual, his travels oscillated between the luxury of foreign courts and roughing it on the road. This time, he traveled with two cats, along with a more typical retinue of local guides and companions.

Landor versus Theodore Roosevelt

Landor first met Theodore Roosevelt in connection with his travels to the Philippines in 1904. Good relations were not long to last.

In 1909, Landor told The New York Times that the ex-president was embarrassing himself by going to hunt in Africa in his old Rough Rider clothes. Landor had toured swathes of the continent himself a few years earlier and painted a portrait of the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik. The region Roosevelt was hunting in, Landor claimed, “could scarcely be called wild.”

To give Landor due credit, he was right about Roosevelt looking silly. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The early 1910s found Landor in Brazil. His goal, which he reported success in, was to penetrate to the interior of the Amazon, proving wrong those who claimed it was impenetrable, and demonstrating the material wealth of the land, to encourage future exploitation. In case you haven’t gathered it by now, Landor was very much on the side of Empire.

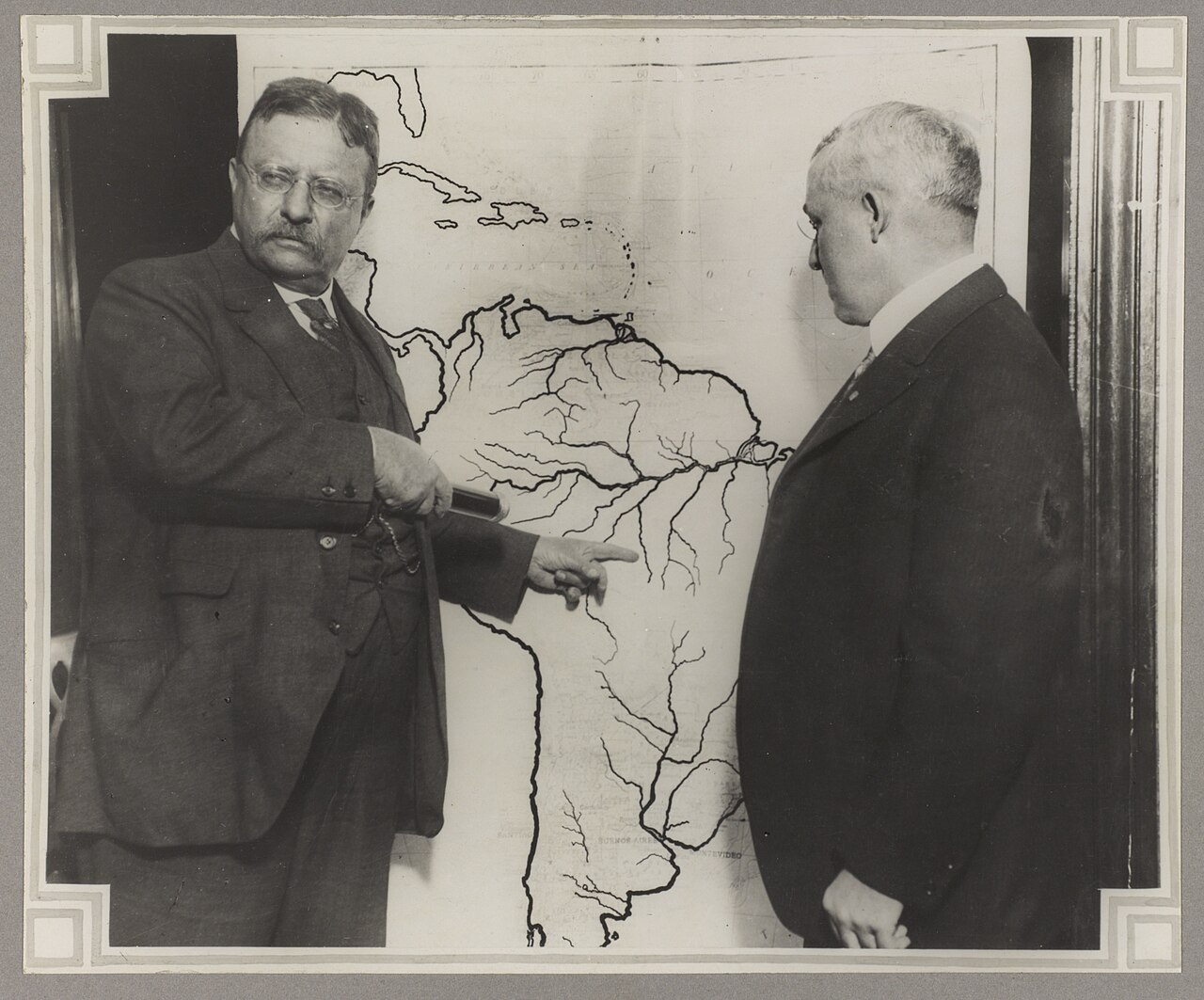

Per his account, he endured starvation, quelled a mutiny of his native guides, forged a road through the jungle, and navigated nearly all the Amazon River. Three years later, Theodore Roosevelt co-led, and nearly died on, a survey expedition along an Amazon tributary.

Landor’s map of his alleged route through South America, his movements marked in red.

An ‘alleged explorer’?

No sooner had Roosevelt returned, health permanently damaged, than he found Landor attacking him in the press, calling the expedition a fraud and Roosevelt a plagiarist, who had stolen parts of Landor’s account for his telling of the expedition. Clements Markham, always ready to weigh in on a messy public debate, agreed with Landor.

Roosevelt, still half dead, fired back immediately, turning the fraud charge back against Landor. He traveled directly to London to begin giving presentations to geographical societies, challenging Landor to show up if he dared. It seems Landor found other places to be at the time. In fact, according to Roosevelt’s private letters, two of his companions had previously been on Landor’s expedition. These two had alleged that Landor was lazy, selfish, and let his native employees do all the work.

American geographers largely sided with Roosevelt, and in 1927, a later expedition confirmed the Roosevelt party’s findings. In a letter to British mountaineer Douglas William Freshfield, Roosevelt said Landor was “as specious as Dr. Cook,” referring to fraudulent North Pole claimant Frederick Cook. In his published book, he called Landor an “alleged explorer.” He was not the first to do so.

Roosevelt, still in poor health, gives a presentation on his expedition to counter Landor’s claims. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The visit to Tibet

Landor’s most controversial exploit was his 1897 Tibet trip. Once again seeking to challenge a land’s reputation for being impossible to penetrate, Landor went to the Royal Geographical Society. He wanted to make this a scientific expedition, so he trained in surveying and astronomical observations at the RGS and took equipment to collect specimens.

Coming only a few years after Francis Younghusband led a failed military expedition into Tibet, it’s clear that Landor was interested in British attempts to open Tibet. In fact, he was approached by the British prime minister, who saw survey work by an ostensibly independent civilian as a way to covertly gather information of military value.

From the Indian town of Almora, he set out with several dozen local assistants, including a man named Chanden Sing, who became his right hand in Tibet. The party entered Tibet through the 5,000m Lipulekh Pass.

His account is one of daring adventure, dodging the Tibetan authorities in pursuit, enduring long marches at high elevation, while gathering valuable geographic and scientific data. Finally, abandoned by all but Chanden Sing and one other, Landor was captured only a day from his goal, the forbidden city of Lhasa.

The trio was held in captivity and tortured, but finally conveyed back across Tibet to British authorities at the border. It was once he got back to England that the trouble started.

Landor and companions, Chanden Sing and Mansing.

Controversy and accusation

Though he had failed to penetrate Lhasa itself, Landor billed his expedition as a remarkable success. He had, he claimed, discovered the Transhimalaya range, as well as the source of the Indus and Brahmaputra rivers. Back home, Landor recalled that being very famous was “a positive trial.” I’m sure.

The Royal Geographical Society, however, declined to invite him to lecture, and their review of his book called his geographical results “unimportant.” The review went on to say his calculations of altitude measurement were “much wanting.” His own account of the adventure showed he could not possibly have had the opportunity to take careful, accurate measurements.

They cited that earlier European geographers had visited the region, and their more thorough findings did not agree with Landor’s. Landor insisted that Lake Manosarovar was not connected to nearby Lake Rakshastal. Previous surveyors said it was.

Alpine Club president Douglas Freshfield wrote to the papers, outlining the unbelievable nature of Landor’s account. To anyone who had actually spent time at high altitudes, the feats of endurance that Landor described, Freshfield argued, were obviously impossible.

Landor fired back, supported by Clements Markham, a highly political figure in exploration in that era. He insisted that his measurements were accurate and that the two lakes were not connected. We now know that they are. The extent of Landor’s deception regarding what happened in Tibet, however, remains a mystery.

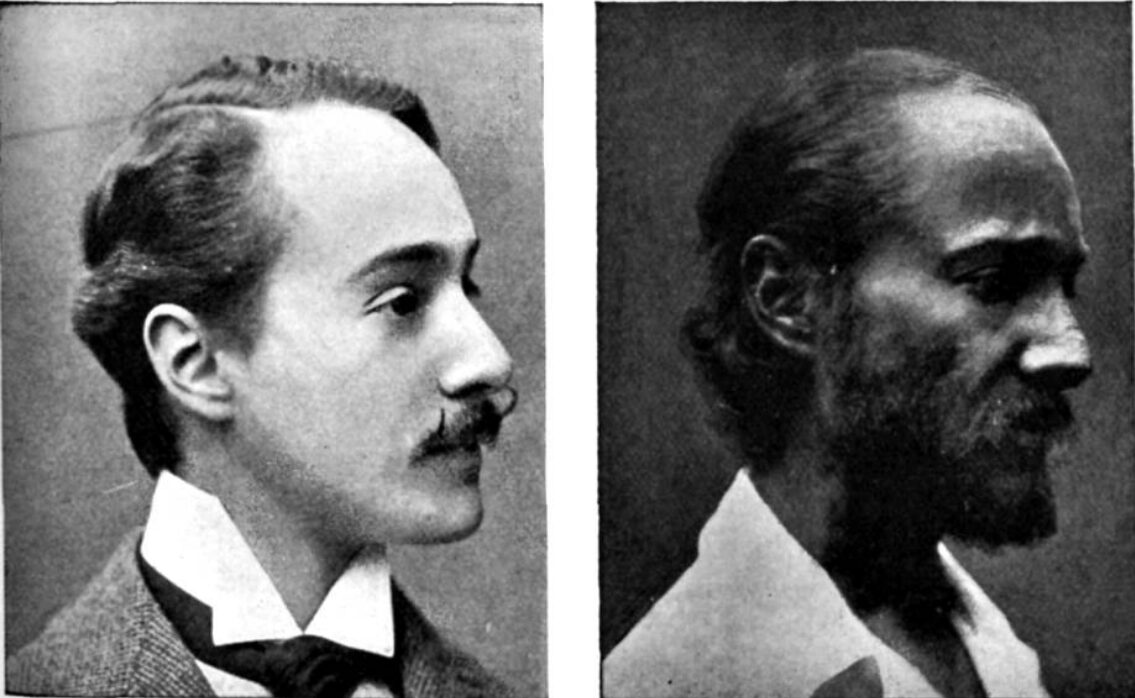

Landor immediately before and after Tibet. It seems likely that the broad strokes of his story — deprivation and capture — are true.

A complicated figure

Landor was always an opportunist and a shameless self-promoter. This is true of many explorers, and it’s what allowed him to do what he did so successfully. It also meant he ran into trouble, made enemies, and announced poorly thought-out ventures to capitalize on whatever was trending in the papers.

One of the stranger instances of this practice came in September 1909. American aviator Walter Wellman had recently failed badly in his second attempt to reach the North Pole by airship. Landor immediately announced his own polar airship expedition, claiming to be building his own craft, which would soon be ready for testing. In it, he expected to reach the Pole and return in less than seven months. Nothing ever came of this.

Years later, Swedish explorer Sven Hedin visited Tibet and charted the Indus and Brahmaputra Rivers to their source. Everywhere I checked, he, not Landon, was credited with that discovery. Landon, of course, called him a plagiarist.

By the late 1910s, Landor finally began to slow down as his health lapsed. Too old to serve actively in World War I, he dedicated his time to patenting designs for airships and armored tanks.

He died in 1924. For all of his success and high connections, today, he is forgotten. His art was last exhibited in the 1950s, and his books are out of print. Perhaps the most terrible fate for an explorer is not to be called a liar; it is to be called nothing at all.