The 2022 spring Himalayan season has ended and everything went reasonably well. There were plenty of summits, local records, and three whole weeks of excellent weather. There were six casualties, but none of these were mountain accidents. While a tragic loss for the families involved, statistically this was a pretty safe season.

Though there was some crowding when big teams, or many small groups, pushed for the summits of Everest, Annapurna, and Makalu, the situation was never out of control. Yet this sedate season may mark a turning point, both in how we understand and how we report on high-altitude climbing news.

The mountains are the same, but the consumer profile has changed. As a result, strategies and business plans have adapted.

Three women

Spanish climber Sito Carcavilla climbed Everest after attempting Dhaulagiri with Carlos Soria. He felt slightly out of place in an environment that he described as “fun, but definitely not a mountaineer’s atmosphere,” in an article for Desnivel. As an anecdote, he mentioned three women in his team who were dancing at a Base Camp party, celebrating their summits. Chinese climber He Jing had just summited without supplementary O2, Sophie Lavaud was celebrating after climbing Lhotse (her 12th 8,000’er), and the third woman was a recent summiter with no previous experience. The third climber’s main concern was whether her skin looked glossy after the climb and whether her make-up would do the trick for her next Instagram post.

The anecdote illustrates the large number of women now on the highest mountains and the massive differences in their abilities.

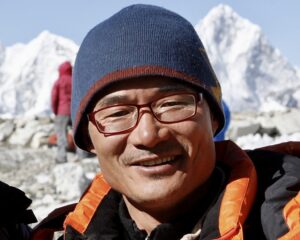

He Jing of China summited Everest without supplementary O2. She climbed her first major peak, Cho Oyu, in 2016.

No-O2 Everest for one Chinese woman

This season, He Jing was the only woman who summited Everest without O2. In fact, she was the first woman to have done so since Carla Perez in 2016 and one of only five since the turn of the century. While she made some headlines at home in China, He Jing, 34, has flown completely under the radar internationally.

Besides climbing, He Jing is a photographer. She documented many sections of the climb on her way up Everest. Photo: He Jing

Jing was one of only four climbers who announced no-O2 Everest ascents this season. That’s a very low number considering the long period of good weather that permitted no-O2 climbers to set their strategy and climb at their own pace.

Sophie Lavaud joins commercial teams while ticking off peaks for her 14×8,000’er project. After Lhotse in spring, she hopes to summit Nanga Parbat in the next few weeks and Shishapangma next year. She started her project in 2012, climbing one or two peaks a year, and then three in 2019. And yet, compared to younger peak-hoppers bagging four 8,000’ers per season, Lavaud seems slightly old-fashioned.

Sophie Lavaud on her way up Lhotse, among dozens of climbers. Photo: Sophie Lavaud

As for the unidentified Instagrammer, she is one of a growing number of inspirational figures catering to social media audiences. Rather than their feats, Instagrammers primarily promote themselves, whether on Everest or in Paris.

Ultimately, the women mentioned are enjoying themselves and achieving goals in the style that suits them best. They are also customers in a thriving business. But they are no longer news.

The multi-headers

As usual, there were new records based on nationality, gender, age, and race. Among these, more than half were achieved by women. This season, women have also led the way with multiple summits.

Kristin Harila on Everest. Photo: Kristin Harila

Helicopters, new O2 systems that permit a flow of eight litres per minute, limitless supplies, enhanced training in hypoxic conditions, and more Sherpas fixing routes all help make multiple climbs in the same season easier than ever.

Climbers such as Grace Tseng, Adriana Brownlee, Jill Wheatley, Purnima Shrestha, Baljeet Kaur, and Kristin Harila have proven that climbing multiple 8,000’ers in a short period is not an impossible achievement but a feasible goal. It depends not only on technical skill, but on efficient logistics, good luck with the weather, willpower, physical strength, and usually on an expert guide leading the way. Namely, Nima Gyalzen with Tseng, Gelje Sherpa with Brownlee, Mingma Sherpa with Kaur, and both Pasdawa and Dawa Ongchu with Harila.

Adriana Brownlee and Gelje Sherpa are a well-coordinated climbing pair. In this photo, they pose on the summit of Annapurna with rope-fixer Pasang Norbu. Photo: Adriana Brownlee

Summit-bagging fever seems to be catching among young climbers, both male and female. Gelje Sherpa, Brownlee’s 28-year-old guide, is racing for the title of youngest to summit all 14 8,000’ers. Were he to achieve it, he might not hold the record for long. Twenty-year-old Pakistani climber Shehroze Kashif already has seven 8,000’ers under his belt.

The proliferation of multi-headers may be a logical (or inevitable) result of ever-improving expedition logistics and the search for new records. However, it is progressively turning what was extraordinary into just another climbing category.

Few facts

Finally, 2022 has been different in a more subtle way. Everest and the 8,000’ers have generated little news this season. Thankfully, some of this owes to the absence of major accidents or tragic events. But there is more to it.

Crowding was not a serious problem this year, although the upper sections were still busy at times. Photo: 8K Expeditions

Nepal’s Department of Tourism has repeatedly tried to control or limit the flow of information coming from the mountains, afraid that the industry is getting bad press because of trash and overcrowding. Last year, they issued some strange regulations, including prohibiting photographs of members from other climbing groups. No one took it too seriously at the time, but teams do appear more cautious about what photos and videos they share.

There was a time when expedition companies sent daily dispatches from Base Camp. Now, climbers can update their Instagram from Camp 4, but summit pictures usually come one or two days after the climber’s summit. Often, reports are clearly PR-oriented, offering few details about difficulties, conditions, morale, etc. Some companies just list their summiters and move on.

Instagram climbing

Individually, climbers can communicate with the outside world very easily but most show little interest in sharing expansive, diary-like updates. Instead, Instagram poses are very much in vogue. These images may only appear days or even weeks after a climb. Trackers are common among climbers but are not always available to the public. Sometimes they are switched off during a summit push.

Uta Ibrahini’s track on Makalu, May 9.

Cautious reporting from the mountains can, contrary to what is intended, raise suspicion among readers and the media. Silence and lack of data create fertile ground for half-truths, false claims, and staged situations. Meanwhile, the bulk of the mainstream audience is not interested in the details, as long as the pictures look good and the narrative gripping.

None of this is illogical. Companies wish to protect their business from controversies and bad press, and social-media-aware climbers have the right to manage their public image as they see fit. It is the age of Instagram mountains.

However, the media’s role is not to parrot public relations messages for the climbers and companies. The result? Less news.

Numbers and business plans

In spring 2022, Everest saw some 650 summits from Nepal (we are waiting for Nepal’s authorities and The Himalayan Database to provide final figures). Nearly two-thirds of them were workers. Nepal’s Department of Tourism issued 325 permits to clients from 59 countries. This includes Nepalis but not working staff and local guides. Alan Arnette estimates that 240 of them summited, an impressive 74% success rate. May featured more than just a good weather window: Almost 20 days had good or very good weather.

Climbing figures were strong on the rest of Nepal’s peaks too. There were 26 permits granted for Annapurna, 27 for Dhaulagiri, 69 for Kangchenjunga, 135 for Lhotse, and 50 for Makalu. If we add Everest, Ama Dablam (with 98 permits), and lesser peaks, a total of 986 climbers paid a fee to climb a peak. Prices ranged from NR500 (about $4) to climb Mt. Urknmang (6,150m), to Everest permits costing a whopping NR3,355,000 ($27,011).

In the Khumbu Icefall. Photo: Pemba Sherpa

Everest income

In total, Nepal’s government earned nearly $4 million in permit fees. Everest alone generated $3,285,743, 83% of the total permit revenue.

In addition, according to prices set by local and international outfitters, every climber setting foot above Everest Base Camp paid between $37,000 and $300,000. Other expenses are spread between helicopter companies, local staff, lodges up and down the Khumbu Valley, and businesses from Namche Bazaar to Kathmandu.

The revenue from climbing royalties is slightly lower than last year when climbers were desperate to be on the mountain after the pandemic lockdowns. However, permits for other 8,000’ers are growing, and the expectations for 2023, both for Everest and other peaks, are very optimistic.

Mountain tourism is essential to Nepal’s economy, and Everest is the goose that lays the golden egg. No wonder those in the high-altitude business do their best to feed it, even at the risk of overstuffing it.

As for the mountaineering media, it too will adjust. There are always stories worth telling, and there are still plenty of opportunities for adventure in Nepal’s Himalaya.