Inside their complex colonies, ants take on one of several vocations: hunter, engineer, soldier, explorer, queen — and hitchhiker?

When car owners filed reports of temporary ant infestations in their vehicles, the stories circulated on social media. In the incidents, which took place in heavily populated north and central Taiwan, thousands of ants crowded into car trunks, crevices, or even engine compartments.

Danger danger Ant-Voltage! 😂🐜⚡️🚗

Returned to disconnect the car from the charger this morning & found these guys going about their business.

Removed adaptor carefully & carefully removed Ants on the floor so they all return home safely. #poletopole #nissanariya pic.twitter.com/iQDvJFkAHl

— Pole to Pole EV (@PoletoPoleEV) August 8, 2023

In all, researchers found nine species of largely invasive, tree-dwelling ants hitching free rides. But could they actually be migrating on purpose?

Six-legged hitchhikers

Virginia Tech entomologist Scotty Yang led a study that leveraged citizen science to investigate. According to his team, the ants are in fact looking to broaden their horizons — and their territory.

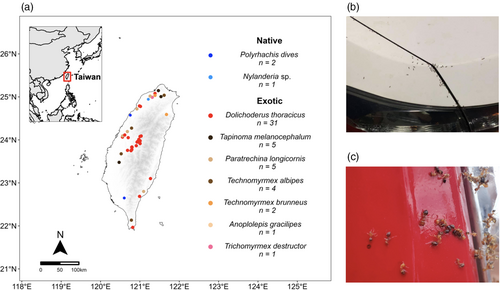

The team documented 52 cases of “ant hitchhiking” on 44 cars and eight scooters from 2017 to 2023. In each event, a car or scooter owner spotted a swarm of ants on their car, then joined a Facebook group Yang started and reported where they were parked, how long they had been there, and where they were going next.

While some cases looked like foraging, many related more closely to the ants’ “exploratory” behavior, the study found. Workers sometimes escorted a queen and larvae into a car that was empty of food or other attractants, presumably focused on finding a new area to colonize.

Hitchhiking ant data. Photo: Yang et. al

Of the nine ant species represented in the study, seven were invasive. Territorial expansion is integral to every invasive species, Yang pointed out. Ants like the black cocoa ant (Dolichoderus thoracicus), which accounted for 60% of the hitchhiking, thrive outside their own habitats because they can overwhelm competitor species in others.

Cocoa black ant. Photo: Jonghyun Park via Wiki Commons

“Tracking invasive insects and how they spread is an important subject for entomologists because these creatures can represent threats to native species of plants and animals,” Yang told Earth.com.

In the urban jungles from which the ants were mainly migrating, the impulse to move out makes sense. Researchers already knew ants in crowded areas often transported their colonies from trees onto building surfaces or other fixtures.

Effective, invasive, pervasive?

If the black cocoas and other ants in the study were looking for new neighborhoods, their strategy was sound. Yang’s research found they could have traveled several hundred kilometers in the infested vehicles — “largely exceeding” their natural ability to spread through dispersal.

Repurposing human infrastructure to do it also made sense. Taiwan is one of the world’s most densely populated countries, so wildlife corridors are often choked by sprawling cities. Ants in the study shared the common factors of strong climbing ability, heat tolerance, and aggressive foraging instincts.

To cling onto their arboreal homes, ants like black cocoas use hooked claws and retractable adhesive pads on their feet. Exposed to the elements, they don’t benefit from temperature-regulated underground nests like other ants. And, the study said, they’re notably vigilant. Because their canopy habitat has limited resources, they “exhibit frequent foraging activities and territorial patrolling” around their nesting trees.

Finally, every driver in a hot city loves a shady parking spot — usually right under a tree.

The authors admitted their study’s volunteer setup limited data availability. But they also suspect ant hitchhiking is far more common than they currently grasp.

Yang’s project envisions a future framework for managing the adaptive technique. The stakes could be high.

One of the world’s most successful invasive ants is also a freeloader. Yellow crazy ants (Anoplolepis gracilipes) find frequent passage on cargo ships transporting produce. Though their original habitat is disputed, they now occur throughout the Indo-Pacific region and Australia. There, they notoriously pillage ecosystems with their acid-spraying attacks and gargantuan colonies.

On Christmas Island, colonies ballooned to 750 acres as they decimated a local crab species, fundamentally altering the forest understory and now endangering even mature trees.

Conservationists think they might have never arrived in the first place — without hitchhiking.