On Dec. 3, 1827, an engraving changed the world of ornithology forever. Robert Havell Jr. of Edinburgh made the engraving, which was based on a painting by a man who had bet his career on its success.

The painting’s artist was John James Audubon. Born in Haiti in 1785, the illegitimate son of a sugar plantation owner, he had dedicated his life to his work as a self-taught artist and ornithologist. After a stint in France, he moved to America at age eighteen, where he obsessively hunted and sketched the birds around him.

Around 1820, after over a decade in business, he decided to make his hobby his career. Intending to paint every American bird, he set out into the wild with a gun and his art supplies.

The result was 435 plates of detailed, lifelike avian illustrations. But the American public wasn’t interested, so he took 250 of his best plates on a ship to England and began exhibiting there. The jewel of his collection was his large painting of Falco Washingtonii, which was chosen as the first engraving and published to drum up interest in his work.

Today, John James Audubon’s name is synonymous with ornithology. But how far would he go to get his work to the public? Photo: Wikimedia Commons

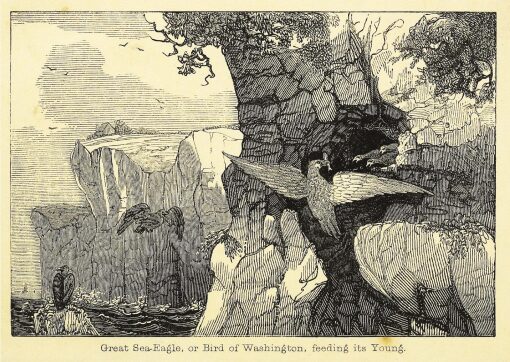

Falco Washingtonii, the Washington sea eagle

The regal bird, perched on a cliff face and overlooking the sea, was a new species, and not just any new species, but the largest eagle in North America. Patriotically, Audubon named it after George Washington. It has been called, interchangeably, the bird of Washington, Washington sea eagle, great sea eagle, and sea eagle.

According to Audubon, it was a bird with reddish-brown plumage, notably larger than any other American eagle. The specimen Audubon painted had a three-meter wingspan and stood a meter tall; its sharp hind talons were over six centimeters long.

The public, and Audubon’s fellow naturalists, were astonished by the discovery. It was a career-making moment for Audubon, and it helped him secure funding to print his seminal work, Birds of America.

The problem? As Matthew Halley has pointed out in his thorough and excellent analysis of Audubon’s supposed Washington sea eagle, there has never been a confirmed specimen. Today, it is not considered a species because of a lack of evidence. So why did Audubon seem so sure it existed?

There are, broadly speaking, three possibilities: He mistook a known animal for a new species; he was lying, and possibly even plagiarized the illustration; or he was right, and the giant North American eagle disappeared before its existence could be verified.

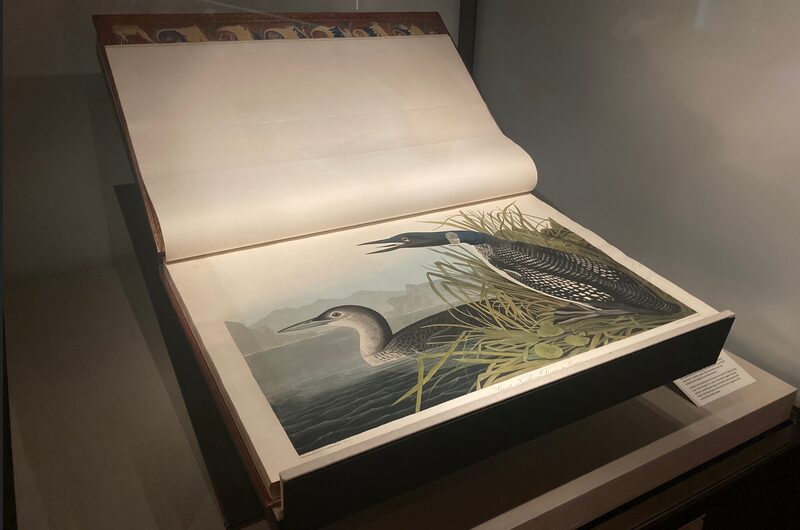

The original folios of Birds of America now reside behind glass in museums and university special collections libraries. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Birds just look like other birds sometimes

We all know the distinctive white head of the bald eagle, but only mature birds have that feature. For the first year of their lives, bald eagles have completely brown plumage. The next few years are an awkward, patchy, white-bellied stage. Finally, around year five, they attain the classic white head, brown body combination.

When juvenile bald eagles leave the nest, they have reached their full, impressive adult size. While not as big as the purported Washington sea eagle, the largest bald eagles can have a wingspan of 2.3 meters. It can be difficult to accurately judge the size of a moving object at a distance, and in his excitement over sighting a big bird he didn’t recognize, Audubon could easily have remembered the animal as larger than it was.

The problem is, he also claimed to have measured an actual specimen. It was significantly larger than even the biggest bald eagles. It was supposedly a male — usually up to 25% smaller than females — suggesting a female of this new species would be even bigger.

Audubon knew that juvenile bald eagles were brown, and this larger specimen was distinctive. He also claimed to observe a breeding pair with chicks, which could not have been juveniles. Finally, bald eagles do not nest on cliff faces, but in trees.

A mature bald eagle, left, perched beside a juvenile. You can certainly see a resemblance between the juvenile and depictions of the Washington sea eagle. The black beak, which turns yellow with adult plumage, is another similarity. Photo: Shutterstock

Sea eagle timeline

There is more than motive to suggest Audubon’s account wasn’t honest. Looking closely at his timeline, the math doesn’t quite add up.

According to Audubon, he first saw the eagle in February 1814. He described “rapturous feelings” at the sight of the large bird flying over his pontoon boat on the Upper Mississippi. His companion, a Canadian, calls the bird a “great eagle,” which he claimed was a very rare eagle, larger than any other, that roosts on rocky cliffs.

Audubon saw the bird again “a few years afterwards,” near the Green River in Kentucky. There, high on a rocky cliff, he saw a nest and watched a mated pair of sea eagles bring fish to their chicks.

Two years after seeing the nest, Audubon had another encounter. Again in Kentucky, this time near the Ohio River outside the town of Henderson, he saw a large brown eagle fly up from a hollow and perch on a low branch. Audubon crept forward stealthily. Once in range, he shot it with his double-barreled hunting rifle. It fell, dead, and Audubon was delighted.

This, according to Audubon, is the specimen on which he based his official description and painting. His last sighting of a living Washington sea eagle was in November 1821, when a pair of them flew over his boat at the mouth of the Ohio River.

The 1835 book A Familiar History of Birds: Their Nature, Habits, and Instincts included the Bird of Washington uncritically, reproducing their rocky cliff nests. Photo: Edward Stanley

The holes in his story

Critical readers of his account had a few questions. Why wait until 1828 to publish anything on this new species? He’d procured the specimen (which he was never able to produce) in 1821 at the latest. During the seven years he waited to publish, he was periodically broke and attempting to gain funding for his work. Surely, revealing this exceptional new species would have been helpful.

Another oddity: according to his diaries, it was only in late 1820 that he began to think that there were two eagle species, one brown and the other white-headed. But eight years later, he claimed to have known since 1814 that there was a larger brown eagle.

This 1820 diary entry, in which he wrote about seeing a group of brown and white-headed eagles, is probably the “last sighting” he claims took place in 1821. He wasn’t at the mouth of the Ohio River in November 1821, but was there in November 1820. His timeline doesn’t line up. Could it be that the entire account given in 1828 was invented?

Plagiarism accusations

There’s no doubt that Audubon was an extraordinarily skilled artist. He used thin wires to arrange his freshly deceased specimens in lifelike poses, and had a very strong visual memory. But he drew from life, not from imagination. So, how could he draw a bird he hadn’t seen?

Over a century and a half after the painting was unveiled, historian Linda Dugan Partridge noticed a similarity between it and an 1802 print in The Cyclopædia, a serialized British encyclopedia. It depicted a golden eagle, the other species of eagle native to North America.

Original, left, and Audubon’s, right. Audubon’s greater artistic skill may have obscured the plagiarism. Photo: Hathi Trust/Wikimedia Commons

In Audubon’s written description, he specified that his bird had twelve tail feathers. But in his painting, the bird has ten, matching the golden eagle print. Feather count aside, from subjective observation, there is something stiff and old-fashioned about Audubon’s painting. His birds are usually livelier and more dynamic. The Washington sea eagle seems posed, statuesque, but not in a good way.

Then there’s the matter of the foot. The feet are unlike those of any known eagle species. What they are like is a second illustration from The Cyclopaedia.

Left, the engraving in The Cyclopaedia, right, a close-up of Audubon’s painting, flipped horizontally. The plated scales, which go all the way down to the toes, are not characteristic of other eagle species. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

An international debate

In an obvious bid to inspire patriotic feelings, Audubon named the bird after America’s first President. “If America has reason to be proud of her Washington, so has she to be proud of her great eagle,” he wrote. Challenging the bird, therefore, would be challenging Washington, challenging America itself.

Nevertheless, some experienced ornithologists on both sides of the Atlantic began looking askance at his eagle.

In 1831, Audubon claimed there was a specimen of the bird in Philadelphia. Several local ornithologists visited the purported Washington sea eagle, which a friend of Audubon’s had bought and donated to a museum. Among them was George Ord, who examined the specimen and declared it identical to juvenile bald eagles he had seen. Another ornithologist, Titian Peale, came to the same conclusion.

Unfortunately, the eagle specimen didn’t survive, so we can’t confirm their findings. But Ord was sure, and wrote pages and pages of scathing letters dismissing Audubon’s claims.

But the public loved Audubon. They were, as Ord opined, “determined to make him a great man in defiance of truth and common sense.”

As the decades went on, the scientific community grew more skeptical about Audubon’s eagle, though public support for Audubon stuck. By the late 19th century, naturalists were sick of the whole debate. Ornithologist Elliot Coues said in 1876 that “this eagle business is about done to death…That famous ‘bird of Washington’ was a myth. Either Audubon was mistaken, or else…he lied about it.”

George Ord published the first scientific descriptions of animals like the grizzly bear, pronghorn antelope, and prairie dog. Photo: American Philosophical Society

A lost giant of the skies

Despite the compelling case against Audubon, there are still those who argue that he was right. There had, after all, been birds of prey of the size he described, and larger, on the North American continent in the past. Buteogallus woodwardi, or Woodward’s eagle, lived in the United States and Cuba during the Pleistocene. Paleontologists estimate it grew over a meter tall with a wingspan of up to three meters.

Outside of the Americas, we find even larger extinct birds of prey. Haast’s eagle flew in the skies of New Zealand until 1445, when competition with early Māori settlers drove it to extinction. These eagles grew up to a meter and a half in length and had comparatively short wings for their body size. Even so, their wingspan may have been as wide as three meters.

Giant eagles aren’t wholly a thing of the past, either. The Steller’s sea eagle can have a wingspan of over two meters. They live in the Pacific Far East, such as northern Japan and Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. Like the purported Washington sea eagle, they nest on rocky outcroppings.

This painting, which imagines a Haast’s eagle attacking a pair of up to 200kg moa, shows its intimidating size. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The skeptic is not always right (often, though)

There is also a precedent for Audubon being correct. Naturalists of his day claimed his depiction of a rattlesnake attacking a mockingbird nest was unscientific because rattlesnakes can’t climb trees. We now know that they can.

Botanists mocked him for his painting of the common American swan, which featured a yellow water lily. Fifty years later, the yellow water lily was discovered in Florida.

Species thought extinct have reappeared in the past, and enthusiasts of speculative zoology are quick to point out that animals like the platypus and giant squid were once thought to be hoaxes. A lost giant eagle, now extinct, is a romantic prospect. But it is far from the most plausible one.

Audubon called the yellow water lily ‘Nymphaea lutea.’ It was rediscovered by botanist Mary Treat in 1876. Photo: Birds of America via University of Pittsburgh library

Time will uncover the truth?

Audubon has a complicated legacy, to put it mildly. That business I mentioned he was engaged in before he dedicated himself to birding? It was slave trading. On his journey down the Mississippi River, two enslaved black men accompanied him. When they arrived in New Orleans, Audubon sold them into the cotton farming industry. He used the profits to help fund Birds of America.

Later in his career, Audubon helped collect specimens for Dr. Samuel Morton’s anthropological work. Morton was establishing scientific racism by developing a ranking of human races by cranial capacity.

Audubon’s contribution included the skulls of five Mexican soldiers, scavenged from a battlefield, as well as looted indigenous remains. Once, for instance, he came upon the tree-burial of “a three-year-dead Indian chief, called the White Cow.” Audubon cut down the chief’s body and unwrapped the buffalo skins he had been lovingly interred in. He sawed off the head for Morton and left the rest of the body on the ground.

Suffice to say, possibly lying about an eagle species is far from the biggest problem with Audubon’s legacy. But the Washington sea eagle issue raises questions about the scientific legitimacy of work that underpins two centuries of ornithology.

What does it mean for American birding that the father of it all likely built his career on a scientific fraud? When it comes to evaluating his legacy, what should weigh more heavily, fraud or racism?

Audubon’s motto was Le temps decouvrira la vérité — “time will uncover the truth.” Let’s hope that he was right about that.

Readers who want to learn more about this should consult Matthew Halley’s thorough account here.