Many animals withstand freezing temperatures partly thanks to hollow hairs. These hairs, with millions of little dead air spaces, provide incredible insulation.

New research shows that the inner structure of the hollow hairs changes between seasons, making the fur warmer in winter and cooler in summer, so that their owners are always at a near-perfect temperature.

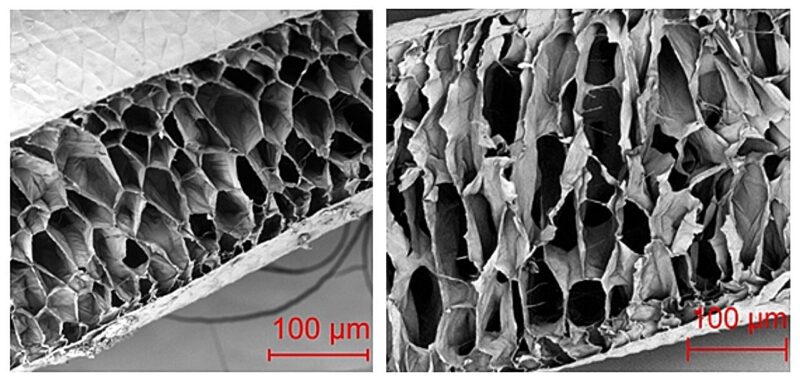

Previously, most research focused on domesticated animals. This study looked at wild animals and how the hair structure changes during the year. Using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), the researchers analyzed hair samples from three animals: Rocky Mountain elk, mule deer and pronghorn antelope. They got the hair from local taxidermists and the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. The SEM revealed an intricate honeycomb-like structure of tiny air pockets on all the hairs.

Pronghorn antelope. Photo: Shutterstock

The scans showed how these air pockets change between seasons. As it gets cooler, the size of the air pockets in all three animals increased dramatically. In mule deer, for example, it doubled from 13 micrometers in summer to 26 micrometers in winter.

“With some animals, the coat looks different in summer and winter,” said study lead Taylor Millett, a student at Utah Tech University. “But…it’s not just the outer coloring of the hair that changes. The inner microscopic details also change.”

Mule deer. Photo: Shutterstock

The SEM uses a beam of electrons to scan the surface of an item. To prepare the hairs, Millett sliced the hairs open, then coated them in gold to improve the resolution of the images. This is when she saw the stark differences between winter and summer hair.

Now the team would like to extend the study. They are currently unsure if this features only in the animals of the region, or if it is widespread.