Teams started arriving at Annapurna Base Camp last week. Incredibly, summits could start before the end of this week.

Looking back 20 years, it is hard to believe we are speaking about the same mountain. The old Annapurna had fewer climbers, a very low success rate, and many tragedies. It also featured more adventure, and, surprise, two other mountain faces to consider attempting! For better or worse, the risk isn’t the same today, either.

2024 – hurry, hurry

Seven Summit Treks, the company in charge of fixing the ropes on Annapurna, hasn’t a moment to waste. The sooner they finish, the faster their personnel will helicopter to another mountain. Most will go to Dhaulagiri and Everest.

In the few days they have worked on Annapurna, the sherpa rope fixers have already reached Camp 2.

“The team is planning to fix the remaining section from Camp 2 to the summit [on April 2],” expedition leader Chhang Dawa Sherpa said.

According to Allie Pepper of Australia (one of the few commercial climbers who is using no supplementary oxygen), the weather is not good. But the rope team is at work, anyway.

Annapurna was the first 8,000m peak to be summited, in 1950 by Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal of France. However, by the turn of the millennium, Annapurna was the least attempted and least summited of all 14 8,000’ers.

1970s-2010s: The age of the bold

Yet expeditions went there nearly every year, although summit options were scarce, and climbers assumed a high risk. The goal with Annapurna was to make it down alive. It was a peak for seasoned, self-sufficient climbers only.

The 1970s and the 1980s filled a good number of pages in mountaineering history on Annapurna: from Chris Bonington and the UK team’s first ascent of the South Face in 1970 (by Doug Haston and Don Whillans) to Messner and Kammerlander’s 1985 climb of the Northwest Face for the first time (Guinness World Record controversy notwithstanding). In 1987, there was the first winter ascent by Jerzy Kukuczka and Artur Hajzer.

Even after these firsts, climbers kept going to Annapurna for what most considered their ultimate challenge. Some sought new, high-difficulty routes on the mighty South Face or the endless East Ridge route. A handful tried to repeat Messner’s 1986 success on the Northwest Face.

Others gambled with the avalanche-prone north side, via either the classic French or German routes. Because of its danger, the first 14×8,000m collectors usually left Annapurna till last. Some excellent climbers lost their lives there, such as Alex MacIntyre, Inaki Ochoa de Olza, Young-Seok Park, and Anatoli Boukreev.

Ueli Steck solos a new route on the South Face of Annapurna in 2013. Photo: Ueli Steck

2015 – Changing trends

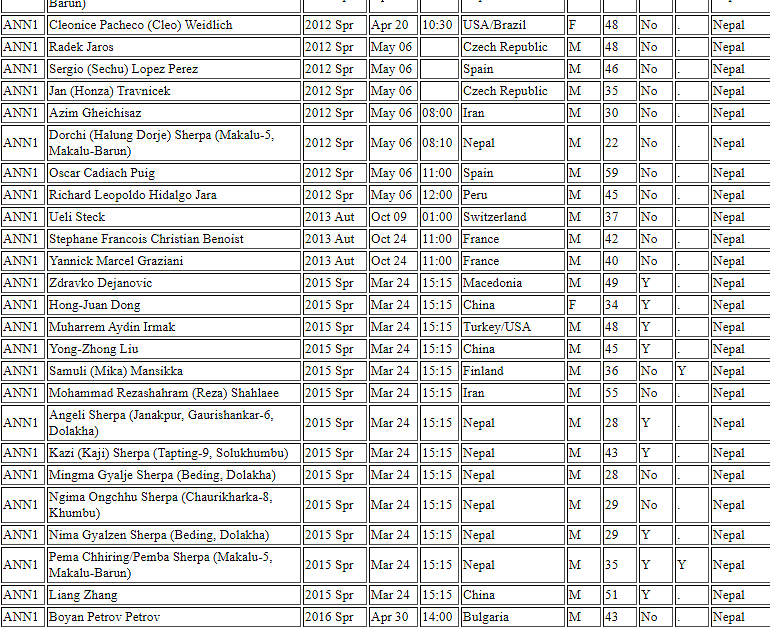

Things started to change in the 2010s. Until then, ascents with supplementary oxygen were extremely rare. Around 2010, some climbers from India, China, and a few working sherpas began to do oxygen-assisted climbs.

Then in 2015, the tide suddenly turned. Climbers on oxygen equaled and then surpassed those without. The number of Nepalese climbers also grew remarkably. Interestingly, the name Seven Summit Treks appears for the first time in The Himalayan Database’s Annapurna archives, although company founders Chhang Dawa Sherpa and Mingma Sherpa had themselves climbed Annapurna some years earlier, in 2010 and 2011. The other founder, Tashi Lakpa Sherpa, has not yet done so.

Extract of The Himalayan Database’s Annapurna summit list for 2012-2015. The use of oxygen is noted in the ninth cell.

From 2015 to 2023, only five expeditions attempted routes other than the normal North Face. None of them were successful. In the last decade, only Adam Bielecki, with various companions, has kept trying a different goal: a new route on the NW Face. On his fourth attempt in 2023 with Pawel Haldas, he ended up saving the life of Anurag Maloo of India on the normal route. This spring, Bielecki is not going to Nepal.

The most dangerous peak switches back to Pakistan

According to the statistics of The Himalayan Database, Annapurna has a total of 476 summits and 73 deaths. Given that the convention for calculating relative risk on 8,000m peaks is done by dividing the number of summits by the number of deaths, Annapurna is no longer the most dangerous 8,000’er. That dubious honor goes back to the original Killer Mountain, Nanga Parbat, according to statistics compiled by Rodrigo Granzotto of Brazil. (The Himalayan Database does not register records from Pakistan.)

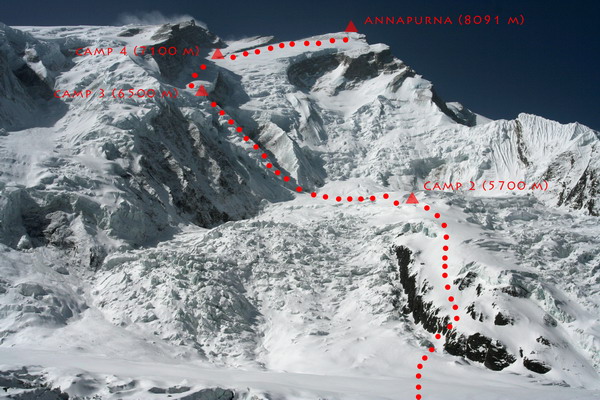

Does that mean that Annapurna is suddenly less dangerous? Not exactly. The normal route involves a serious risk of avalanches, especially between Camp 2 and Camp 3. There, pieces of serac fall from the notorious ice barrier on the upper sections of the mountain.

Annapurna’s normal route. Photo and topo: Ferran Latorre

Why are climbers safer now?

The key change today is the vastly greater number of seasonal summits. In the entire 20th century, since its first ascent in 1950, 110 people summited Annapurna. That’s one less than the number of summits registered in the last two years alone! (There were 111 summits in 2022-2023). The summit waves of recent years have skewed the statistics. But that’s not all.

A line of climbers heads toward the summit of Annapurna in 2021. Photo: Pasang Lamu Sherpa Akita

In addition, scaled-up expedition logistics, with fixed ropes, limitless use of oxygen, and a huge staff of rope fixers and supporting sherpas have improved safety, because everyone spends less time on the mountain. Climbers jumaring up fixed ropes are much faster, and the oxygen allows them to summit with just one rotation — or even none, in some cases.

The Nepalese guides know every millimeter of the route. They know the safest spots to set the lines and pitch the camps. Drones assess conditions on sections above the climbers, and helicopters have improved rescues. As seen in 2021, they may also resupply teams as high up as Camp 4.

The situation is not exclusive to Annapurna. Currently, the rope fixing on Dhaulagiri, led by the Pioneer Adventure team, is progressing at the same swift pace. Camp 2 is already awaiting clients. Whether we like it or not, the logistics worked out on Everest have been applied successfully to the rest of the 14 highest peaks.

Yet it would be unwise to underestimate any of these mountains, especially Annapurna. Every season still features rescues, some bordering on the miraculous. And people still die, as Noel Hannah did from illness on his way down the mountain last year. Zero risk is not an option on any mountain, least of all on the biggest ones.