Captain Thomas Dudley’s ship, the Mignonette, had sunk beneath him 17 days earlier, and he and his three-man crew were trying to survive in their lifeboat. Dudley had once been a cook, so he had experience butchering animals. Perhaps this is why he was holding the penknife. Perhaps he felt it was his duty as captain to take the worst (or, at least, the second-worst) job. Maybe he was just the hungriest.

It was July, 1884. Dudley crouched in the bottom of the rickety craft, the sun blazing above him and the unconscious body of a teenage boy beneath him. Dudley offered a brief prayer to God, struggling to speak through the dryness of his mouth. He told the mate to hold down the boy’s legs if he struggled.

Hearing the voice of the captain above him, Richard Parker, 17, blinked awake. The boy’s eyes were discolored, likely blind, and he seemed confused.

“What — me, sir?”

“Yes, my boy.”

With one hand, he adjusted the young man’s head, tilting it up to reveal his bare neck. Then he slipped the penknife into the exposed flesh, cutting into the windpipe and opening his carotid artery.

He used the bailing bucket to catch the blood, which he drank thirstily along with Stephens, the mate. The dying Richard did not call out or struggle, but his body twitched, and his wound made a terrible sucking, gurgling sound.

Mad with hunger and thirst

A third man, who had turned away from the proceedings, emerged from beneath the canvas he had hidden under. Thirst and hunger had overcome his horror now that the deed was done, and they shared the blood with him. Long before the wound ran dry, Richard Parker was dead.

Dudley cut out his liver and heart, then butchered the rest of the boy’s body. They used the brass oar lock as a butcher’s block to protect the thin wood planking. Dudley and Stephens rinsed strips of flesh in the ocean and laid them out to dry. They threw Parker’s intestines, genitals, and feet over the side, and sharks immediately began fighting over them.

When they were rescued by a passing ship four days later, the men made no effort to hide Parker’s remains. They were open about what they had done. Why wouldn’t they be? It was terrible, but the men thought it was perfectly legal.

The lifeboat where Parker died was exhibited in Falmouth later in 1884. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Custom of the Sea

Sailors called it “the Custom of the Sea.” When wrecked or stranded without food, everyone in the group would draw lots. The short straw was killed and eaten. It was better for one to die than all.

Of course, the lotteries weren’t usually fair. Reviewing incidents of the Custom of the Sea, a pattern quickly emerges.

In 1759, those aboard a ship called the Dolphin were without food. According to survivors, a Spanish passenger drew the unlucky short straw. The crew shot then beheaded him, discarding his head but devouring the rest. Another ship rescued the survivors before they had to kill again.

Six years later, the crew of the Peggy was in a similar situation. The sailors told their reluctant captain that they had drawn lots, and the short straw had gone to an enslaved black man. He was killed and eaten. The next time lots were to be drawn, the captain insisted on overseeing affairs, suspecting that the draw had not been entirely fair. This time, it fell on a popular white sailor. Instead of killing him, the crew delayed for several days until they were rescued by a passing ship.

In 1874, the Euxine sank in the South Atlantic. A series of misadventures found five survivors in an open boat without food. One of them was a “dark-skinned Italian boy,” who did not speak English. They drew lots three times and, according to the survivors, the young Italian man had the incredible bad luck to draw the short straw on all three occasions. They were rescued only hours after the young man was dispatched and eaten.

Though cannibalism was not included in Theodore Gericault’s well-known painting, ‘The Raft of the Medusa’, it was depicted in his preliminary sketches. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Don’t be a cabin boy

When racial and ethnic minorities were not available, the next people on the menu were the youngest members of the crew. You might think it would be the other way around — wouldn’t the older men try to protect their young compatriots? Just the opposite, it turns out. The justification was that young boys did not have families relying on them financially. They were also the lowest in the pecking order and the easiest to overpower physically.

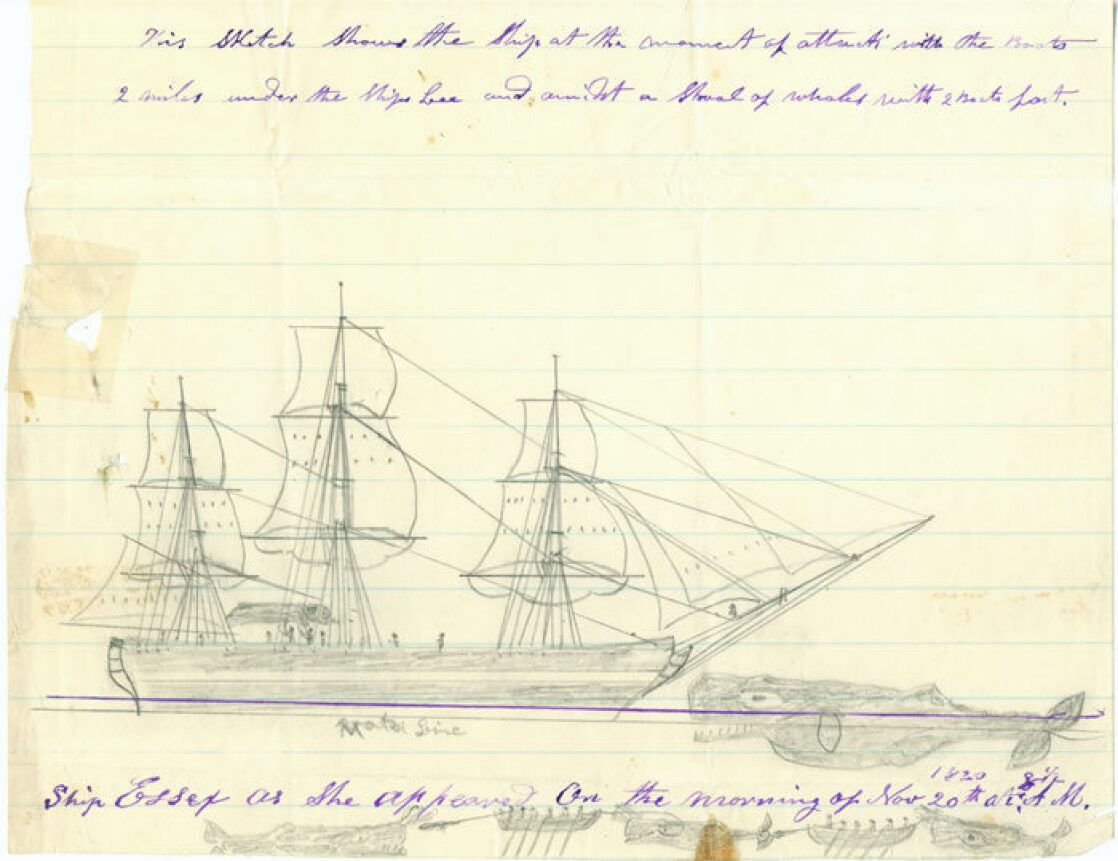

One of the lifeboats following the infamous wreck of the whaleship Essex drew straws, and the lot fell on 18-year-old Owen Coffin. According to survivors, the black seamen had already died of natural causes and been eaten.

Owen Coffin’s fellow cabin boy, Thomas Nickerson, drew the whale attack which sunk the ‘Essex’ in 1820. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

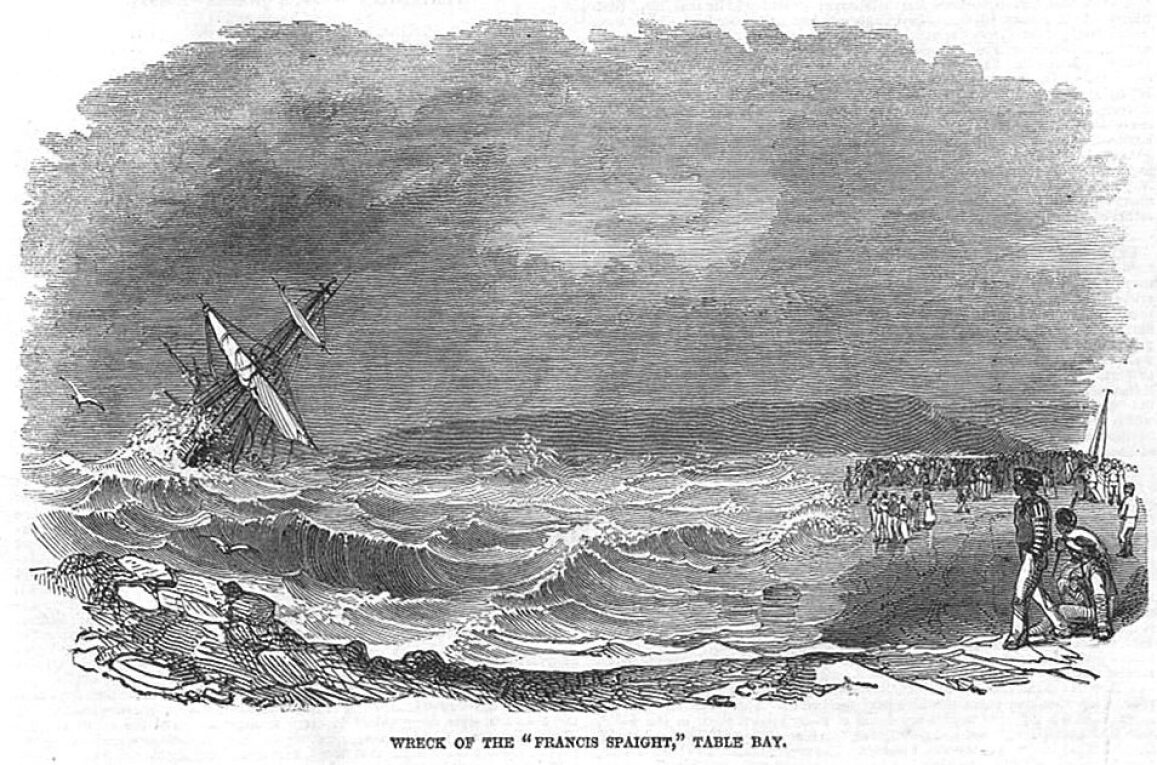

The ‘Francis Spaight’

The clearest case of selective boy-eating occurred in December 1835 on the Limerick vessel Francis Spaight. A storm tossed the ship on its side, drowning three men. The rest were forced to cut away its masts so it would right itself. This prevented them from drowning but stranded them on a mastless, drifting ship. Most of their food and supplies disappeared in the storm. After two weeks, Captain Gorman decided a lot must be cast…between the four cabin boys.

Fourteen-year-old Patrick O’Brien protested that this wasn’t fair. He had agreed that lots should be drawn, but among the entire crew. The draw went on, anyway. In what could have been a coincidence, the short straw went to Patrick. Though he resisted, verbally and physically, brandishing a small knife, the boy was overpowered by the captain and several crewmen, who slit his throat. Contemporary newspaper reports, which were sympathetic to the crew and captain, say only that lots were drawn. The courts acquitted the captain and crew of murder.

The actual Custom of the Sea wasn’t to draw lots and eat the loser. It was to eat the cabin boys, passengers, and racial minorities, then make vague gestures at lot drawing to preserve plausible deniability. But for hundreds of years, English law courts accepted this thin pretense.

This illustration of the wreck of the ‘Francis Spaight’ appeared in the Illustrated London News. The public ate up, if you will forgive the pun, stories of maritime disaster, the gorier the better. Photo: Illustrated London News Archive

The ‘Mignonette’

To return to the Mignonette: A wealthy Australian lawyer named John Henry Want recently bought this 16-meter yacht in the UK and wanted it transported back to Australia. A racing and leisure vessel, the Mignonette was not designed for the open sea and was entirely unsuited for the 24,000km journey from Southampton to Sydney.

But practicality rarely stops the kind of man who buys a yacht on a whim while on a business trip. Want hired Thomas Dudley, who found three sailors to crew the vessel. Want promised a large reward in exchange for the danger: £100 in advance, with a further £100 on delivery of the yacht. An average sailor’s yearly wage at the time was less than £50.

Dudley was an experienced sailor with a reputation for being sober, dependable, and fair to those working under him. He planned to use his share of the money to buy a home in Sydney and pay for passage over for his wife and their children.

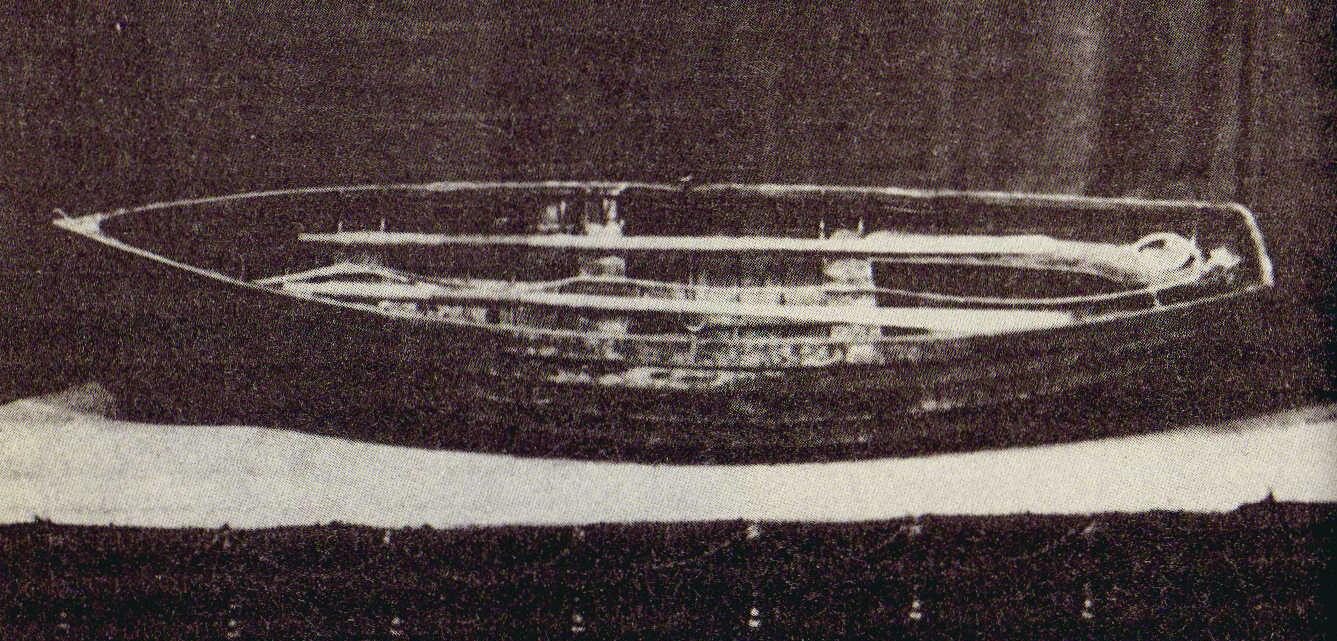

Thomas Dudley’s drawing of the Mignonette. Photo: Public Record Office, London

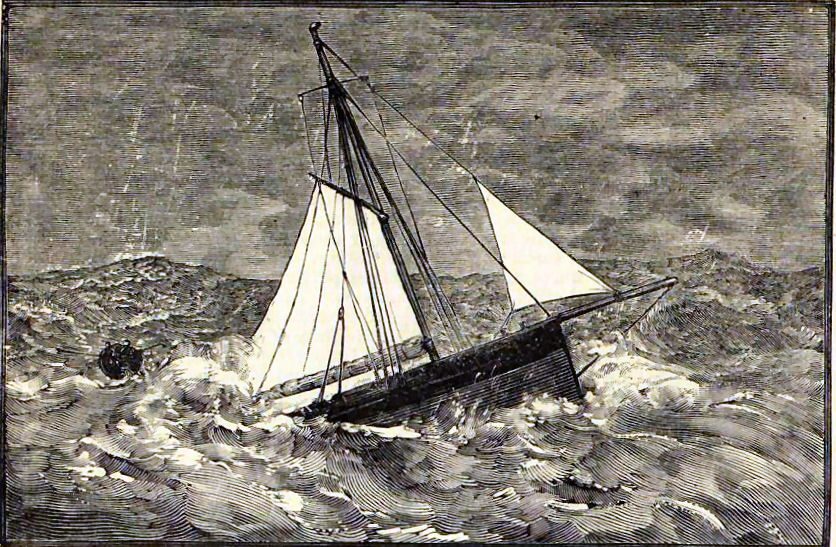

The inevitable sinking

Dudley had serious misgivings about how the yacht would fare in the open sea and took out a hefty life insurance policy on himself before leaving. With him were a mate, Edwin Stephens, a sailor, Edmund Brooks, and the cabin boy, Richard Parker. He was an orphan, small for his age, with little sailing experience. His pay would be a little over a pound a month, plus food and accommodation.

Dudley was right to be worried. A little over two months after setting off from Southhampton, they battled ferocious winds and seas that the old yacht couldn’t handle. She sunk 2,500km off the African coast.

All four sailors managed to escape into the four-meter dinghy, but Parker was injured and badly shaken up. They had no water or fishing gear. The only food they’d saved was a kilo of turnips.

The ‘Mignonette’ was old and not built for the open sea. Photo: Illustrated London News Archive

Three weeks adrift

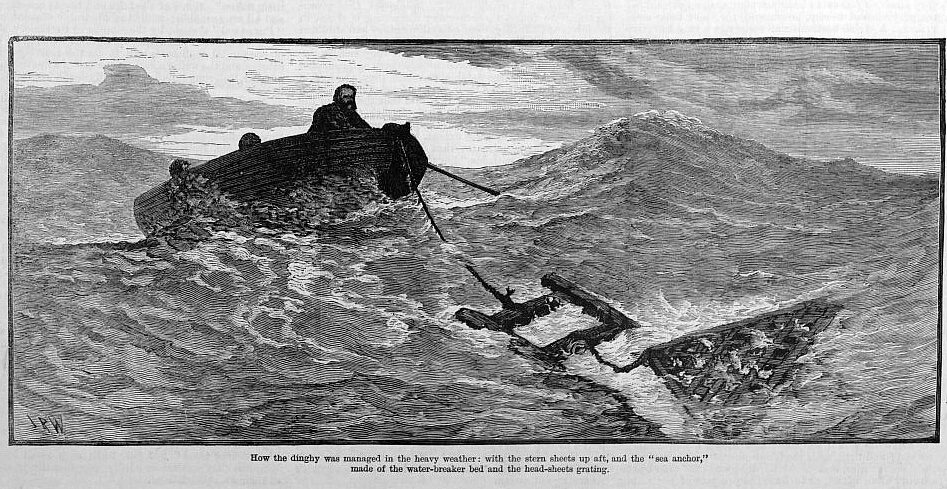

Dudley also salvaged navigational equipment. Acting quickly, the veteran sailor constructed a sea anchor to guide their lifeboat, then set course for the nearest shore. Dudley rationed the turnips strictly, and they had a stroke of good luck when they managed to catch a sea turtle.

But if the food situation was dismal, the water situation was truly desperate. They weren’t able to gather the little rain that fell, and the men resorted to drinking their own urine. The experienced sailors knew never to drink seawater, but the temptation was terrible as thirst became all-consuming.

Parker struggled the most. At one point, he fell into the sea — or perhaps jumped — and had to be rescued by Dudley. The captain repeatedly cautioned Parker not to drink seawater, which they used to rinse and wet their mouths.

This Illustrated London News drawing shows how Dudley steered the small boat with an improvised sea anchor. Photo: Illustrated London News Archive

Seawater and blood

On July 17, Dudley raised the idea of drawing lots but to little enthusiasm. That same day, a devastating disappointment rocked them all. They sighted another sailboat, but the ship refused to help them, saying they had nothing to spare, and left.

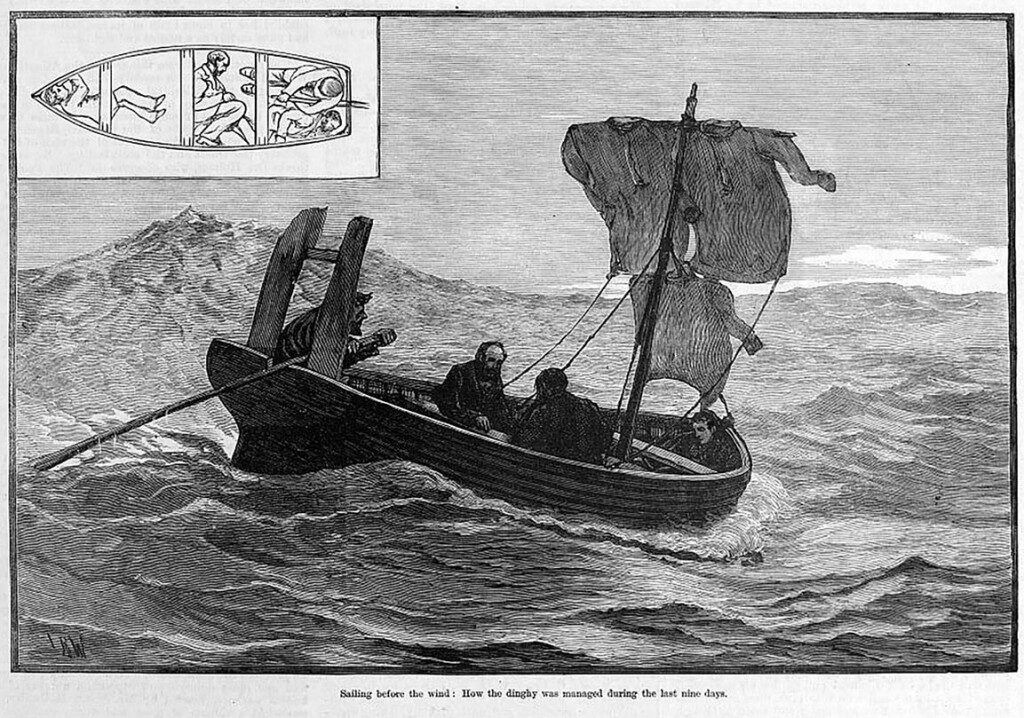

Three days later, Parker became horribly ill. Stephens claimed to have seen him drinking seawater despite their injunctions, and now the boy could do little but curl up in the bottom of the boat. Delirious, he begged for a ship to come for him while the others attempted to comfort him. By the seventeenth day in the boat, Parker appeared to be comatose and dying. Talk again turned to lots.

Brooks argued that they had to wait for Parker to die on his own. But if they did, they wouldn’t be able to drink his blood and slake their thirst. Their thirst would kill them long before they starved. Stephen and Dudley, with a reluctant Brooks, prepared to draw lots. Ultimately, they didn’t bother; they all knew who was drawing the short straw.

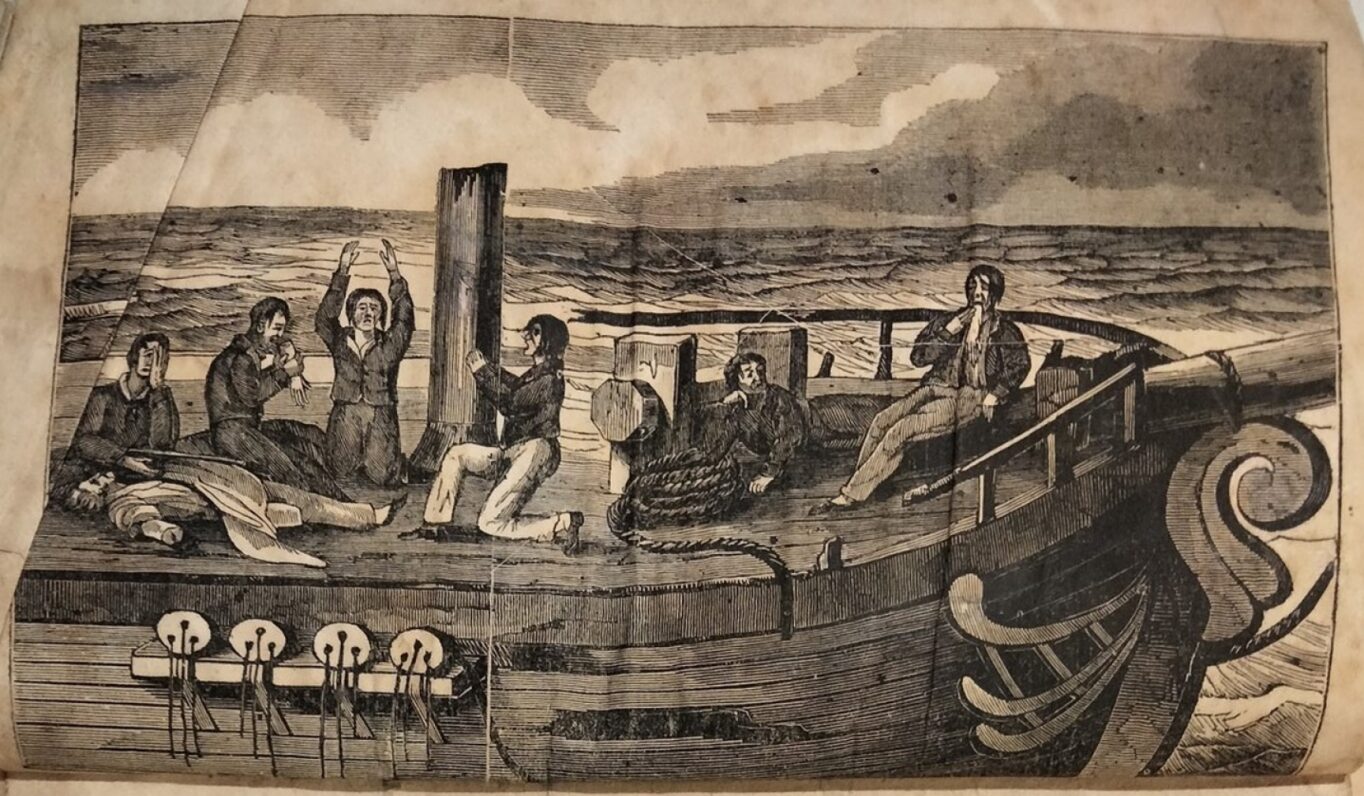

This illustration shows the desperate, cramped conditions in the lifeboat. The three men used their shirts to improvise a sail while they allowed Parker to keep his shirt. Photo: Illustrated London News Archive

An unpleasant shock

A German bark, Montezuma, picked the men up four days later after they had killed and eaten Parker. In September, the three survivors landed in the harbor at Falmouth, back in Britain. They went to the harbor commissioner and explained the story, telling him honestly what they had done to survive. A policeman present, either not knowing or not caring for the Custom of the Sea, was alarmed by the blithely reported child murder and consumption.

He returned with a warrant and placed all three under arrest, with a further two Montezuma sailors summoned as witnesses. A second unpleasant shock came to Dudley and Stephens when they found out that Brooks had turned Queen’s witness, and was going to testify against them.

They had the public’s sympathy, though. Supporters took up a collection for a Mignonette Defense Fund to cover legal fees. Even Richard Parker’s elder brother went to the jail and met with Dudley and Stephens, shaking their hands as a public display of understanding and sympathy. In a testament to public feeling, they were both released on bail to await trial, and messages of support poured in.

But the courts were determined to rule against them.

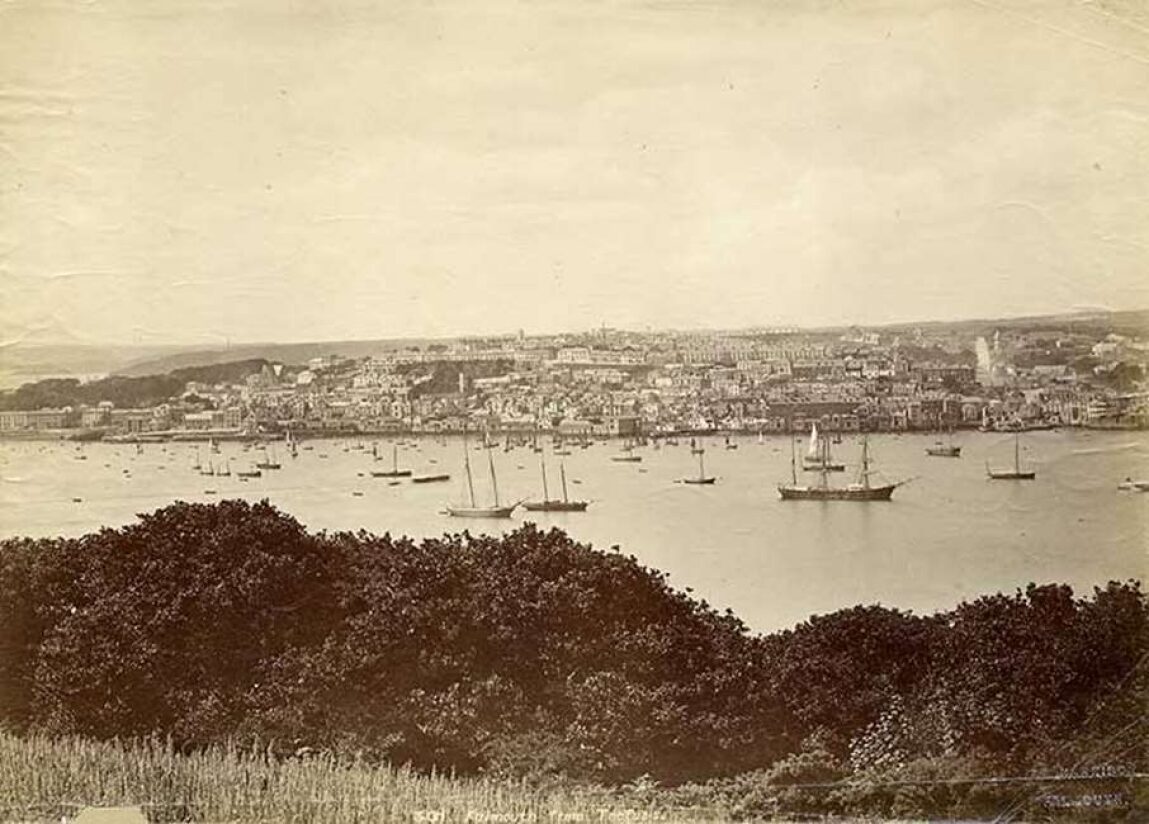

Falmouth harbour in the late 19th century, where the ‘Mignonette’ survivors finally returned to shore. Photo: Historic England Archive

The Queen vs Dudley and Stephens

After an initial investigation in Falmouth, Dudley and Stephens were sent to Exeter to stand trial. The judge was the formidable Baron Huddleston. The Baron was an eminent judge who wore color-coded gloves to court.

For this case, his gloves were black for murder. He was also determined to get a guilty verdict, as the courts had for some time been looking for a landmark case to end the grisly Custom of the Sea. The fact that they didn’t actually draw lots may have made matters worse.

Because the jury was sympathetic to the accused, Huddleston decreed that the jury would only decide the facts of the case, not the verdict. They were found guilty, but the verdict was deferred to a higher court, which Huddleston also served on.

This third round of deliberations took Dudley and Stephens to London. They continued to plead not guilty, with their lawyer citing previous cases of “Murder by Necessity.” Though the court was sympathetic to the difficult position of Dudley and Stephens, they couldn’t set a precedent that allowed cold-blooded murder.

On Dec. 9, 1884, the court declared Dudley and Stephens guilty of murder on the high seas and sentenced them to death.

Left, Chief Justice Lord Coleridge, who presided over the final London trial. Right, Baron Huddleston. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London

Aftermath

Dudley and Stephens were not executed. The court likely never intended for them to be executed. In fact, the court included a recommendation for mercy in the formal decision, kicking the problem up the chain to Queen Victoria herself.

She obligingly commuted the death sentence to six months’ imprisonment. After their release, their statuses as Captain and Mate were restored. Dudley followed up on his plan to emigrate to Australia with his family. There, he started a business making sailing equipment. He died in 1900 of the bubonic plague, aged 46.

As for the Custom of the Sea, English courts didn’t see another case. Perhaps sailors stopped consuming each other; maybe they just stopped talking about it afterward. The custom did stick around longer in other places, such as Norway. Nowadays, though, it is pretty much universally frowned upon to kill and eat your coworkers, even if you are very, very hungry.