Pterosaurs — the family of avian dinosaurs that included the famous pterodactyl — definitely soared through Triassic skies.

However, it’s unclear how they got there.

And that remains the case, despite ongoing research shedding new light on the past lives of our planet’s earliest known flying animals.

Pterosaurs (Greek for “wing lizards”) emerged around 237 million years ago, though the first pterosaur fossil dates to around 219 million years ago. (That’s a bit of a blip in geologic time — the earliest known dinosaur lived 243 million years ago, and the fossil record really picks up 13 million years after that.)

It’s hard to beat the pterosaur’s wild combination of attributes and sheer spectacle. Some pterosaurs were as big as fighter jets, some were as small as songbirds; the fastest ones could reach air speeds north of 100kph. Their hunting habits enabled them to walk on their hind legs with hugely distorted hands as walking sticks. And a huge range of prey prompted them to evolve snarling cages of teeth that jutted out at all angles.

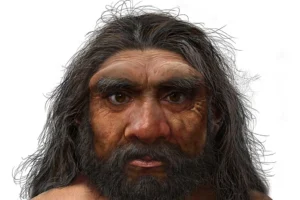

Photo: Flickr

Creatures from nightmares

“Some pterosaurs looked like creatures from your nightmares,” Brian Andres, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Sheffield in England, told Science News.

Though often the subject of famous dinosaur-related phantasms, pterosaurs still don’t exist as solidly in the known paleontological record as some of their headliner contemporaries.

“Often, pterosaur remains are just a jumble of bones,” Matthew Baron, a “freelance vertebrate paleontologist,” told Science News.

Studying early pterosaurs presents strong challenges. Researchers have clearly established their eventual widespread presence, and the winged creatures later evolved into a huge panoply of subspecies.

But the fossil gap in early pterosaurs has prevented a concrete understanding of their evolution.

They hung around water, or in it

There is a relative consensus that they shared a close connection with aquatic ecosystems. Either they principally ate aquatic species, were one themselves — or both.

For instance, a striking fossil record of drowned young pterosaurs exists. Researchers think that comes from their ability to float in order to hunt on water — but maybe not with great posture. And because pterosaurs had powerful flying muscles (rather than structures that prioritized gliding), still-developing juveniles could have had more difficulty lifting off.

Yet whether their closest ancestors originated in the water, on land, or in the canopy above remains unclear. The best bet for a missing link so far is the humble Scleromochlus taylori — a 20cm-long reptile that lived about 230 million years ago. It was a close relative of pterosaurs, according to a study published last year in the journal Nature.

View this post on Instagram

The creature’s proportionally huge head and long femur suggest a relation with pterosaurs, Science News pointed out at the time of the study. And S. taylori is also related to lagerpetids, another family of small dinosaur with similar, running-optimized features.

Promising as the comparison is, some gaps between the species still remain. Pterosaurs’ wings spread from their large hands, especially an extremely elongated fourth digit (most of the leading edge of a pterosaur’s wing would be our ring finger, if it was our hand). S. taylori had relatively small hands.

“We’re missing several intermediate forms in between that bear features related to active flight,” explained Argentine paleontologist Martin Ezcurra, who was not involved in the 2022 study.

Now, researchers hunt that intermediary ancestor, which could have displayed more passive, gliding flight.