Extraordinary coincidences led to a misunderstanding about an accident on the Matterhorn. Yet the lesson remains: Mountaineering is no joke, the Matterhorn is a serious endeavor, and mistakes sometimes exact a high toll.

Two weeks ago, we were shocked to report that three people died on the Matterhorn in two separate accidents. The day that the third solo climber reportedly fell to his death, guide Eukeni Soto was on the mountain with a client.

At 4,200m, with the Hornli route already covered with snow and ice and near the end of the fixed ropes, they crossed paths with a man progressing with some difficulty and inadequate gear: jeans, snow cleats (the kind used by trail runners), and no ice axe or climbing harness. The sight was so scary that the guide stopped for a moment and filmed the rogue climber. Later, he shared a clip on his social media:

When we contacted Soto for details, he said that the guy he had filmed had died on the descent. That was the news he heard after arriving back in Zermatt. Indeed, ANSA (the Italian National News Agency) reported on Saturday, August 17, that a “solo climber” had fallen to his death from the upper part of the Matterhorn’s Hornli route. That word that spread among climbers in Zermatt. ExplorersWeb echoed the story the same day ANSA released the news.

No more details were shared at the time. Soto was genuinely shocked at the man’s casual approach to a serious peak. He admitted he tried to draw the climber’s attention to warn him, but he was ignored.

The good news

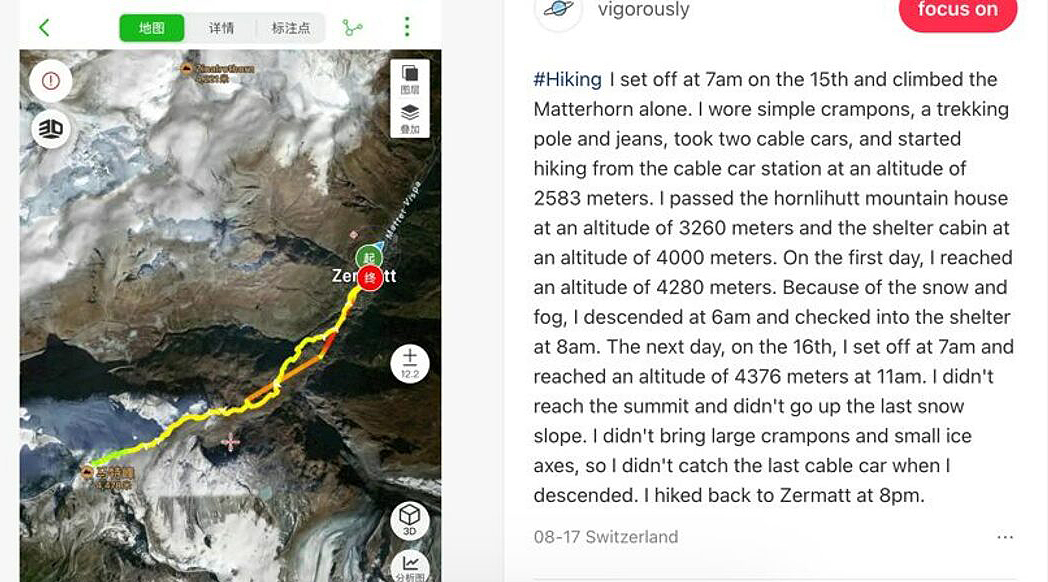

As it happened, the guy whom Soto filmed didn’t die. He eventually turned around and made it back to the Hornli hut. Not happy with the result, he tried again the following day, with the same lack of gear and the same result — but no accidents. We know this now because the climber himself shared the details of his “feat” on Chinese social media. Thanks to one of the commenters on our original story for finding this.

Post by the climber on Xiaohongshu.com

We contacted Soto again for further comments and tried to obtain further details. On an update, ANSA offered no new information but pointed to “imprudence” as the cause of recent accidents in the Alps. But a week after the accident took place, Swissinfo.ch posted a brief story mentioning that the climber who died on Thursday (a day earlier than previously thought) was with a partner, who suffered minor injuries. The climber that Soto saw was alone.

Still tragic, still irresponsible

We apologize for the confusion. Yet, two facts remain: Three people lost their lives on the Matterhorn within a week; that is tragic. And the way the Chinese climber progressed on an exposed 4,478m mountain was irresponsible and reckless. He was putting his life (and perhaps the lives of others below him) in serious danger.

As Soto put it, “It is unbelievable that this guy got so far up, with no equipment and no knowledge.” He may have survived, but he is not an example to follow. Because he made it down safely, he may never know how close to death he was.

For the record, Soto described the situation as follows:

It occurred on Friday, Aug. 16, at around 9:30 am, at 4,200m. Soto and his client had summited and had started their descent 30 minutes earlier.

“As usual on the Hornli Route, I was downclimbing and guiding my client at a speedy pace, but I couldn’t help stopping in my tracks for a moment and film the climber with my cell phone,” he said.

He hoped to share the clip later as a cautionary tale of how not to climb the Matterhorn.

They were at the end of a section equipped with thick, hawser-like fixed ropes. Beyond, the fixed rope ended, and just 100 vertical meters, covered in snow, remained before the summit. The climber was hoisting himself up on a rope with its end buried in snow.

“For some meters, this person had to cling to the climbing rope of another guide, who was leading a client on their descent, until he reached the following rope,” Soto recalled.

Most climbs are guided

The normal route up the Swiss side of the Matterhorn — the Hornli Ridge – involves 1,220 vertical meters of easy but exposed scrambling and climbing. Climbers leave the Hornli Hut at around 4 am in the dark to summit and get down before the typical afternoon clouds cover the mountain.

Eukeni Soto’s client on the summit of Matterhorn. Photo: Eukeni Soto

The climb requires mountaineering boots and, on the upper section, crampons. You also need an ice axe and to know how to use it. As usual in the mountains, the descent is more dangerous than the ascent.

Because of the large number of climbers on the peak every summer, local guides have installed a series of thick ropes and fixed anchors. Clients are short-roped, and guides waste no time with classical climbing techniques. (Check the video below.)

Such an endeavor requires speed, the endurance to scramble up ropes for hours, a steady mind to bear the spooky exposure, and a background in alpine climbing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Most Matterhorn wannabes these days use guides. (Guides operate in a 1:1 ratio.) There are independent teams too, but they are usually slower than the guided pairs. This often leads to tense situations, with guided pairs passing them up and down, which can create safety issues for both teams.

It is unlike Mont Blanc, where there are no fixed ropes, and the snow route offers enough room to pass safely. Matterhorn guides are fast, and to avoid traffic jams, their clients must be able to keep up or turn around.

Soto said that conditions on the mountain were okay that day. “The weather was good, and there was almost no ice on the upper sections,” he said. “But of course, mistakes are not an option.”