Earendel is Old English for “morning star” or “rising light”. The star, which the Hubble Space Telescope recently pinpointed in the void 28 billion light-years away, is the most distant object that humans have ever discovered. The twinkle that Hubble registered has been traveling through space almost since the Big Bang.

Earendel’s astronomical age

If you were around when the universe was young, you might have counted Earendel among the dawn stars. According to a paper published March 30 in the journal Nature, it was born just 900 million years after the universe began.

That makes it 12.9 billion years old, based on estimates that put the universe itself at 13.8 billion years old.

The real mind-blower, though, is the reason why scientists only just discovered it. Because 28 billion light-years of distance yawn between us and it, Earendel’s light didn’t arrive on earth until recently.

The star’s astronomical age could give scientists new insights into the universe’s ever-mysterious origins.

“As we peer into the cosmos, we also look back in time, so these extreme high-resolution observations allow us to understand the building blocks of some of the very first galaxies,” said study co-author Victoria Strait of the Cosmic Dawn Center in Copenhagen.

Strait explained that because the universe constantly expands, Earendel was only four billion light-years away from Earth when the Milky Way formed. Back then, the universe was only 6% as big as it is now.

Warp light, see far: gravitational lensing

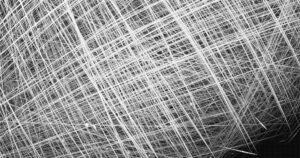

Telescopes capable of identifying and measuring objects so far off do so by using obstructions between the lens and the object of interest as magnifiers.

Albert Einstein discovered this effect, which is called gravitational lensing. It occurs when gravity warps light from more distant objects around closer objects. The closer object deflects light around the distant object, and the resulting angle of deflection can magnify the distant object.

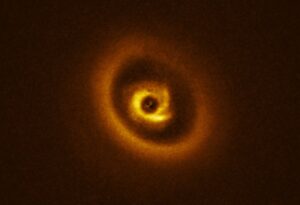

Galaxies in the foreground acted as a magnifying lens, amplifying the light of the distant background star Earendel thousands of times. Photo: NASA/ESA/Brian Welch (JMU)/Dan Coe, Alyssa Pagan (STSCI)

The process often produces fuzzy images. Galaxies are the typical discoveries that come from gravitational lensing, and they usually look like blobs.

But in Earendel’s case, the countless obstacles throughout the 28 billion light-year distance coalesced into an unusually sharp and powerful magnifying glass.

“Normally at these distances, entire galaxies look like small smudges, with the light from millions of stars blending together,” said astronomer Brian Welch of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “The galaxy hosting this star has been magnified and distorted by gravitational lensing into a long crescent that we named the Sunrise Arc.”

The purity of youth: Earendel’s composition

Earendel is also enormous — scientists estimate anywhere between 50 and 500 times the size of the sun. In their next research step, scientists will use the James Webb Space Telescope to try to determine its composition.

Astronomers want to know more about the star’s makeup because if it’s as old as they think, it should be relatively pure — undiluted by the heavy elements released by the deaths of billions of stars since the Big Bang.

If Earendel is mostly composed of primordial hydrogen and helium, it will qualify as a Population III star — the group of stars thought to exist shortly after the birth of the universe.

“Earendel existed so long ago that it may not have had all the same raw materials as the stars around us today,” Welch said. “Studying Earendel will be a window into an era of the universe that we are unfamiliar with, but that led to everything we do know. It’s like we’ve been reading a really interesting book, but we started with the second chapter, and now we will have a chance to see how it all got started.”