It was the day after Christmas 1971, and Juliane Koepcke awoke on the shadow-striped floor of the Peruvian rainforest. She was buckled into a three-person airline bench seat. The plane itself has disintegrated in midair; just the bench seat remained.

The night before, Koepcke had been traveling with her mother from Lima to Pucallpa aboard LANSA Flight 508. The women were on the way back to back home after picking up Koepcke’s high school diploma. The child of two German expat scientists living and working in Peru, Koepcke had been taking classes on and off for years. She was proud of her accomplishment. She saved up to buy a fancy dress for the occasion and convinced her parents she should attend the ceremony in person.

Her mother booked tickets on a Lineas Aéreas Nacionales Sociedad Anonima (LANSA) Lockheed L-188A Electra turboprop for the return journey. This was over Koepcke’s father’s objections — the airline and plane had bad reputations in Peru. The year before, a LANSA flight had crashed, killing all but one of 100 souls aboard.

A Lockheed L-188A Electra turboprop aircraft similar to the one that crashed in Peru in 1971. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“Please don’t fly with LANSA. Any other airline but not LANSA,” Koepcke remembered her father saying.

“I think it will be okay,” her mother responded. She booked the seats, the only two available on Christmas Eve.

It wasn’t okay.

Taking stock

Regaining consciousness in the jungle, she unbuckled and took stock of herself. A 17-year-old girl in a cotton mini-dress with a broken zipper. One white sandal. A bag of hard candies. A concussion, a broken collarbone, and a large cut on her leg. An eye injury. Kilometer upon kilometer of trackless rainforest in every direction. And teenage years that had, improbably, prepared her for just such an occasion.

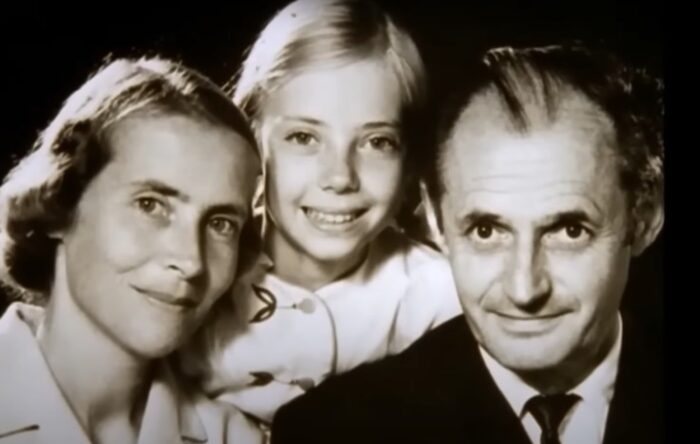

Years before the crash, a young Koepcke (center), poses with her scientist mother and father. Photo: Screenshot/Wings of Hope

In 1968, Koepcke’s family transitioned from an urban life in Lima to a jungle existence, running a research station in the middle of the Amazon rainforest. Koepcke was fourteen, and at fourteen, you have two options in such a situation: Rail against it with all your might or adapt. Koepcke adapted.

In the morning, her family homeschooled her, and in the afternoons and evenings, she rambled the forest, soaking up knowledge from her jungle-savvy parents. For 18 months, she learned how to move through the jungle, how to avoid poisonous plants and dangerous animals, and above all, the mental fortitude the landscape demands. There’s no escaping the bugs, as Percy Fawcett and dozens of other South American explorers have learned.

Above all, she absorbed a key lesson in jungle navigation for the lost — follow a trickle until it becomes a stream, follow a stream until it becomes a river, follow a river until it becomes a larger river. Eventually, you’ll find people. If you can stay alive long enough.

But none of the training in the world can prepare you to fall three kilometers from a disintegrating plane. To survive that, it takes luck and plenty of it.

‘Now it’s all over’

Koepcke and her mother were in a window seat, two rows from the rear. The flight was smooth until the plane descended into a thundercloud in preparation for landing.

“Suddenly, it went very dark as we entered the storm. The turbulence was terrible. Parcels, jackets, bags fell from the overhead lockers, Christmas cakes, and gifts,” she said. “People began to cry and panic. Then I saw a blinding white light over the right wing.”

It was a lightning strike. Kopecke remembers her mother saying, “Now it’s all over,” and then the sounds of 90 other passengers and crew crying out in terror. The deafening roar of engines, the feel of the aircraft in a nose dive. And then:

“The noise was gone. I was outside the plane, and it was completely quiet,” she remembered.

How could she fall three kilometers strapped to an airline seat and survive?

Koepcke examines an artifact from the crash in the 1998 documentary ‘Wings of Hope.’ Photo: Screenshot

Aided by experts, she’s come up with four theories. The seat spun in flight like a maple seed falling from a tree, slowing her fall. A powerful updraft from the storm similarly slowed her. The jungle’s densely woven canopy provided a kind of safety net. And finally, her seat, through random chance, hit the ground with her on top, not underneath.

Chances are it was some combination of all four.

Bird calls

Regardless of how it happened, Koepcke was alive. Injured, traumatized, and mourning the likely death of her mother. But alive, and with the kind of mind that sets survivors apart from the pack.

“I felt no fear because it was the same environment I knew from home,” she said of the moment.

So to business. She knew the jungle she was in was uninhabited but that her plane had been 15 minutes from landing. She knew she’d have to rescue herself if she wanted to live. And she knew she had to find water, both to drink and to follow to rescue. She set out in search of a stream and found one.

Her candy, only meant to sustain her on a short flight, ran out after four days. She slapped endlessly at bugs, and a cut on her arm became infested with botfly maggots. She suffered the rainy season’s relentless precipitation, and when it wasn’t raining, her skin burned from the sun. She stepped carefully, as her parents had taught her, but it was a challenge — she’d lost her glasses somewhere between sky and earth.

Another horror

To make matters worse, after a few days following the stream, she came upon a fresh horror. Another airplane seat — this time with dead passengers buried upside down in the mud. She investigated them just long enough to ascertain none of them were her mother, then moved on.

Afraid of stepping on a venomous snake with her poor vision, and growing ever weaker, she used the stream for travel, floating mid-current to avoid shallow pools where something might take a bite out of her. Hearing a distinctive bird call, a lesson from her ornithologist mother resurfaced.

Koepcke’s survival strategy centered on finding large waterways and following them. Photo: Screenshot

“You only find hoatzins near larger rivers, open water,” her mother had said. The bird calls were coming from a different direction than she was traveling along the stream. It was an inflection point, the kind of decision you only get the chance to make once in a survival situation.

Koepcke left the stream and pushed through the understory, following the bird song. Her gamble paid off. She found a large river.

Hoatzins like large bodies of open water. Remembering this lesson from her ornithologist mother is what saved Koepcke’s life.

She traveled along the waterway for days, surviving on her wits and skills and particular brand of luck in equal measure. She managed to avoid attack by any large predators, and a failed attempt to catch and eat a poison arrow frog probably saved her life. Finally, after ten days in the jungle, she stumbled into a rarely visited logging camp, complete with a hut and a boat. Her luck held. The men who worked the camp returned the next day.

The cut on her arm later produced more than fifty botfly maggots.

PTSD

There’s no surviving something like that without bearing some scars, mental and physical. For Juliane Koepcke, the mental side has been a more challenging road. Heartbroken by the loss of his wife, her father withdrew into his work, and Koepcke was estranged from him for many years.

She suffered traumatic dreams, long crying spells, and other reminders of her ordeal. All this was worsened by the knowledge that other passengers — including her mother — may have survived the crash but perished in the jungle while waiting for help.

Koepcke shortly after rescue. Photo: Screenshot

“My father thought she’d survived for nearly two weeks –- perhaps up to January 6, because when he went to identify her body, it wasn’t as decomposed as you’d expect in that environment,” she said. “It’s very warm and humid, and there are lots of animals that would eat dead bodies. He thought she’d broken her backbone or her pelvis and couldn’t move. It bothers me very much. I think, what must it have been like for her in those last days there?”

Enter Werner Herzog

There was media furor when Koepcke stumbled out of the jungle, but eventually, the attention was too much to bear. She started turning down interview requests, a pattern she held for the next thirty years. She earned her doctorate and returned to Peru to study bats before settling into a comfortable existence as a librarian at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Munich. She married and became a rainforest conservation advocate. Mostly, though, she stayed out of the limelight, trying and mostly failing to process things in her own way.

When filmmaker Werner Herzog contacted her for his 1998 documentary Wings of Hope, she finally broke her media silence. Herzog, long fascinated by death and mortality as subjects, was originally scheduled to be on LANSA Flight 508. A last-minute change of plans in his location scouting itinerary saved his life, and it took him decades to track her down. Koepecke agreed to fly with Herzog to revisit the site of the crash, an experience she later called “a kind of therapy.”

Koepcke accepts an award for her contributions to science in Peru. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Unfinished business

Making the film was a surprising mental and emotional balm for Koepcke. Over a decade later, she wrote When I Fell from the Sky: The True Story of One Woman’s Miraculous Survival. In interviews surrounding the book’s release, she describes writing it as a necessary act, a completion of unfinished business.

So how do you survive a fall from the sky followed by ten days in a jungle? Training, clear-thinking, and knowing when to make hard calls. A heaping portion of grit. Fortitude. And lots and lots of luck.

If you’ve got all that, you’ve got a chance. But as Koepcke will tell you, it’s what comes after that sometimes feels more challenging to survive.