The climbing season has started in the Himalaya, and the Icefall Doctors are already working on Everest’s normal route. Dozens of other Nepalese sherpas are also working on other peaks. Soon, they will guide clients to summits, carry gear up and down mountains, and open routes while fixing ropes.

But these jobs are dangerous. Both the statistical data, via The Himalayan Database, and the individual stories of loss on Everest illuminate the dangers faced by sherpas each season.

The Khumbu Icefall. Photo: Onestep4ward

Not just statistics

Three years ago, I saved a photo of a Nepalese sherpa who died on Everest. I still have it, out of respect and appreciation. It is of Lhakpa Nuru, known by his nickname Tate Lhakpa, from Tate in the Khumbu district. He died on May 29, 2021, from acute mountain sickness at 5,350m. Tate Lhakpa was 42 years old.

There is another image that is difficult to forget. On April 14, 2022, 37-year-old sherpa Ngima Tenji was found dead in a sitting position close to an area known as the Football Field, in a relatively safe part of the Khumbu Icefall. He died at about 4 am while carrying loads to Camp 1. There was a photo published at the time of a helicopter recovering the body by longline.

The late Lhakpa Nuru Sherpa. Photo: Seven Summit Treks

Last year, of the 18 people who died on Everest, one third were sherpas. The figure includes Dawa Chhiri, Lakpa Rita, and Pemba Tenzing Sherpa who died on April 12 at 5,700m in an icefall collapse. Their bodies could not be recovered.

A total of 332 people have died on Everest; 130 of them were working sherpas, more than a third of the total. If we examine the death reports from the last 10 years, between 2013 and 2023, 92 people died on Everest and 47 of them were sherpas.

Not a new phenomenon

The first registered sherpas died on Everest on June 7, 1922. An avalanche at 6,800m killed seven.

The Khumbu Icefall is the most dangerous part of the normal route. Located between Base Camp and Camp 1, hundreds cross it every year. But sherpas cross it more times than clients, every season, year in and year out. Between 1953 and 2023, almost 50 sherpas have died in the Icefall.

On April 5, 1970, six sherpas died in the Icefall from a serac collapse at 5,700m. Another sherpa died four days later in a lower section, at 5,525m.

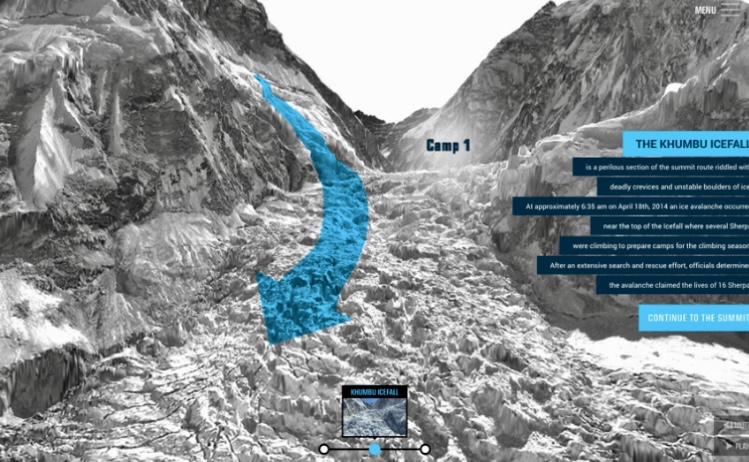

The path of the deadly 2014 avalanche in the Khumbu Icefall. Photo: Snowbrains

On April 18, 2014, at 6:45 am, a huge ice avalanche caused by a toppled serac killed 16 sherpas in the Icefall. A longline operation recovered 13 bodies. After the accident, the sherpa community threatened to strike because the Nepalese government did not offer enough compensation to the victim’s families. Out of respect for their fellow sherpas, they did not continue working that season.

Accidents happen, but unfortunately, it is assumed that some sherpa workers may die every year, as if it were just part of the business. It shouldn’t be normal. Most sherpas now don’t want their kids to remain in the business. It is simply too dangerous.

Climbers head up Everest. Photo: Ngaa Tenji Sherpa

Roger Marshall’s take

In 1986, The New York Times Magazine published “One Man Vs. Everest,” sharing the thoughts of the late British-Canadian climber Roger Marshall. In it, Marshall explained why he would never employ sherpas in his expeditions.

Marshall argued that sherpas have worked for Western expeditions for several decades, doing the dirty work, humping loads up the mountain to stock permanent camps used in siege climbing. Marshall and others pointed out that “the system is not only unsupporting, but unethical, and even inhumane.”

Marshall highlighted that sherpas must make repeated trips along the most dangerous sections of the route, such as the Khumbu Icefall, which becomes a tomb for countless sherpas. “Having seen all the sherpas who are mutilated, the sherpanis who are without husbands, I would never employ a sherpa,” Marshall said.

Crossing the Khumbu Icefall. Photo: Ngaa Tenji Sherpa

Marshall added that “if it weren’t for the money, sherpas would have no interest in climbing because they are hill farmers and traders by tradition, not adventurers. They’re making a living while we’re having a good time, and no amount of money is enough to justify what they’re asked to do.”

Since that article, things have changed. Sherpas have become important businessmen and developed the climbing business, employing many more sherpas than in the 1980s.

Everest Base Camp, 2021. Photo: Kenton Cool