The celebrated trail runner, skimo racer, and speed climber also explains why “world record” makes no sense in alpinism.

Speed records have become fashionable in mountaineering, but so has criticism against some of those claims done without regard to style, context, or proper proof. The term FKT, meaning Fastest Known Time and originally applied just to trail running, has recently entered the mountaineering conversation as well.

We asked Kilian Jornet, for whom speed is his passion and the source of his celebrity, to clear up some of the confusion. He has also shared tips for athletes on keeping their accomplishments free of controversy.

In addition to holding over a dozen FKTs himself, from the Matterhorn to Everest, Jornet is a self-professed “data geek” who has even put together Mountains and Athleticism (MTNATH). This is a free website with information about all categories of mountain racing, advice on training, nutrition, and equipment, and a list of useful online resources. It includes a section about mountain FKTs, defined according to Jornet’s expertise.

Records have equal conditions

To begin with, Jornet noted the difference between a record and an FKT.

“A record is done when all the contenders climb under the same conditions and there are people ensuring the conditions really are equal,” he said. In other words, records require rules, referees, and even anti-doping criteria.

This means that there have to be specific rules about equipment, pacing, support, conditions, and even anti-doping policies, his website explains. Referees from the organization validating the record should be there to verify that those rules are met.

“Otherwise,” Jornet told ExplorersWeb, “it should be considered an FKT.”

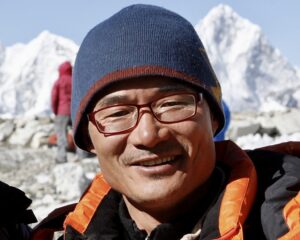

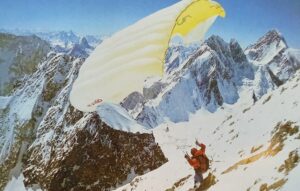

Kilian Jornet flying on familiar routes in Norway. Photo: Kilian Jornet

Jornet explained further: “Records are set on certain mountain races, in which all participants have the same conditions. Sometimes, mountain associations or guiding schools even monitor a speed ascent, for example, by stationing guides on the Matterhorn’s Hörnli route, but this is not the norm.”

He notes that given the controlled conditions, a record can be slower than an FKT that occurs outside an official race or a monitored climb.

Kilian Jornet (left) and David Goettler on Everest last year. Photo: David Goettler

World records

For Jornet, speed records make no sense in alpinism, because conditions make such a difference. The style or support also differs in every case. So it is more accurate to talk about FKTs for alpinism and high-altitude mountaineering.

The term “world record” makes even less sense, says Jornet.

“It should be possible to equal or improve a world record in several places around the world. So why should speak of world record or world first, when referring to a time over a specific route, such as the Colorado Trail or the GR 20 [a 180km path across Corsica] or a cycling challenge like the Alpe d’Huez?” Jornet said. “What you have then is an FKT on a specific route, in a specific place, in a specific style.

“In the end, it is not really possible to compare two alpine or high-altitude climbs, even if the route is the same. Some factors — conditions, weather, and so on — will always be different.”

But Jornet says that FKTs are still interesting from an athletic point of view, “to check how fast someone can go across a particular terrain, under certain conditions and support.”

Below, as an example, is Benjamin Vedrines’ impressive FKT on the Spaghetti Tour in the Italian Alps.

On his website, Jornet lists different FKTs on mountains — both ascents and linkups. He parses the style beyond the simple “supported” or “unsupported” favored by trail-running websites. He includes details such as solo, rope solo, onsight, and first ascent. Here’s the table: mtnath.com/fkt/

“I don’t count any climb supported by PEDs [performance-enhancing drugs],” Jornet says.

He is referring both to people who acknowledge that they take drugs like EPO, but also supplementary oxygen.

O2 like e-bikes

Jornet is very strict about what it really means to climb no-O2.

“For me, going without oxygen means that no one on the team uses it and that there is no oxygen available if something goes wrong,” he says. In this, he is similar to those professional climbers past and present, who go no-O2 or not at all, including Denis Urubko, Reinhold Messner, Jerzy Kukuczka, Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner, Andrzej Bargiel, and Kim Chang-ho. Carla Perez, another no-O2 practitioner, said more about this in a past interview with ExplorersWeb.

Yet Jornet is not against using oxygen, “as long as it is properly reported,” he says. “I believe O2 is great for mountain tourism because it increases safety. But nowadays, when it comes to an FKT or a new route, it makes no sense to count O2-assisted climbs.

“O2,” Jornet adds, “is like an e-bike. I love riding them, they’re fun, and they allow less well-prepared people to access routes they couldn’t otherwise. But we can’t take seriously a cyclist who claims a speed record on the Alpe d’Huez while riding an e-bike.”

How to set an FKT

So what should a mountain athlete do to properly set an FKT, especially on 8,000m peaks?

“First, they must be crystal clear about their style,” Jornet said. “Ueli Steck used to note that he did the Eiger in 2 hours and 47 minutes in 2008, with no packed trail or ropes. In 2015 he completed the same route in 2 hours and 23 minutes, but he always remarked that, although he was faster, he used the ropes and ran on a well-broken trail.

“Everyone needs to be equally transparent about support, ropes, trails, onsight or not,” Jornet says.

“Also, you need to provide as much proof as possible to document the climb: witnesses, tracks, GPS watch, camera metadata,” Jornet noted. “Technology can provide a great deal of information about a climb.”

What if someone lies? What if they cheat about the style that they used, or dissemble in some other way?

“Well, lying about something like that is not a big deal in the history of the world,” says Jornet. “It’s just a rich person’s problem. But as with doping in sports, it distorts the reality of a performance. We push our limits to see how far the body can go with certain training and conditions, and doping distorts what we can really achieve as humans.”