Throughout history, mountains have provided refuge for outlaws. High passes, dense forests, hidden caves, and steep cliffs allowed these figures to ambush travelers, evade authorities, and launch raids before vanishing back into the complex terrain. Many began as ordinary people driven into crime by poverty, injustice, or war. Some became feared criminals, and their elusiveness made them real nightmares to authorities.

Unlike the largely fictional Robin Hood, the outlaws whose stories we’ll tell today were real men who lived and died by the gun and the blade. Their stories often blend daring exploits with violence. Some became folk heroes and carved legends that are still remembered today in popular culture. Over the next few days, we revisit the stories of some of those legendary bad guys around the world who plied their trade from the safety of their mountain fastnesses. Today: the betyars of Hungary.

The Gerecse Mountains in Transdanubia, where beeches grow in dense stands and wild boars grunt from the undergrowth. Photo: Kris Annapurna

The Betyars, Hungary’s romantic outlaws

In the 19th century, the dense, shadowy woods of Hungary became the playground of the betyars (Hungarian outlaws). They weren’t just common criminals, but symbols of rebellion against feudal misery and Habsburg authority. While the most famous betyar of all, Rozsa Sandor, operated mostly on the open expanses of the Great Hungarian Plain, others made their home in the highlands of the Bakony Mountains, Transdanubia, and the Matra Mountains.

(Note that in Hungarian, the family name comes first, as in Japan, China, Korea, and Vietnam. Here, we will follow this convention.)

Sobri Joska. Photo: Bakonycentrum.hu

Sobri Joska

A romantic betyar icon, Sobri Joska (1810-1837) went from a simple pig thief to the most wanted man in Hungary. He was active in the Bakony Mountains. His 1836 raid on Colonel Hunkar’s estate was the stuff of legend. He didn’t just rob the place: He also locked the guests in the cellar and vanished with their silver and guns.

It took a massive, multi-county manhunt to finally corner his gang at Lapafo in 1837. There, according to some sources, he decided to shoot himself rather than endure capture. Though some say he died in the shootout or on the gallows, others insisted that he slipped away to live a quiet life under a fake name.

Adding to his mythic status was his legendary romance with Repa Rozi (“Carrot Rosie”), a fiery red-haired servant girl who fled to a roadside inn after defending herself against a nobleman’s assault. According to folklore, Sobri fell for her instantly, protected her, and made her his betrothed. Folk songs immortalize their passionate yet chivalrous love. She disappeared mysteriously after his death.

Sobri Joska’s hideout in the Bakony Mountains. Photo: utirany.hu

Vidroczki Marton

Another of Hungary’s most famous betyars, Vidroczky Marton (1837–1873), also features in many folk songs and legends.

Born near the Bukk Mountains to a poor rural family, Vidroczki worked as a shepherd in his youth. The stories vary on why he turned to outlaw life. Some say that he deserted from the Austrian Habsburg army after a conflict while serving as a trumpeter. Others claim that an employer mistreated him brutally or peg it on a romantic tragedy.

He began his betyar “career” after escaping from a military prison by drugging the guard and jumping into the Danube. He and his band committed robberies and became wanted men throughout the country. Folk tales describe him as handsome, generous, vengeful, fond of revelry, and even “bulletproof.” (!)

Vidroczki Marton enjoys some revelry between raids. Photo: Kekesonline.hu

Though he was born near the Bukk Mountains and active there at first, Vidroczki spent the final phase of his outlaw life in the Matra Mountains, hiding in remote villages and caves. He was betrayed and killed on February 8, 1873, at age 35. He was reportedly ambushed by Pinter Pista, one of the members of his outlaw band, during an internal dispute.

His legacy is a Matra cultural heritage, a subject of ballads and songs. Folk dance groups even perform his story.

‘Sour Joe’

A bit later, Savanyu Joska (“Sour Joe”) took up the mantle as Hungary’s chief betyar. He was a short, multilingual man who knew the Cuha Valley’s tiny caves better than his own home in the Bakony Mountains. He was brutal and fearless.

In 1881, Savanyu committed one of his most notorious crimes during a failed robbery attempt, when he and six of his men surrounded the manor of Kalman Haczky, a Hungarian nobleman and landowner. Savanyu’s group had learned that Haczky was keeping a big sum of money at home after a land sale. When the robbery took place, Haczky was playing cards with guests at home, including Antal Bogyay, a former judge. Bogyay tried to escape by jumping out a window, when one of Savanyu’s men shot and killed him instantly.

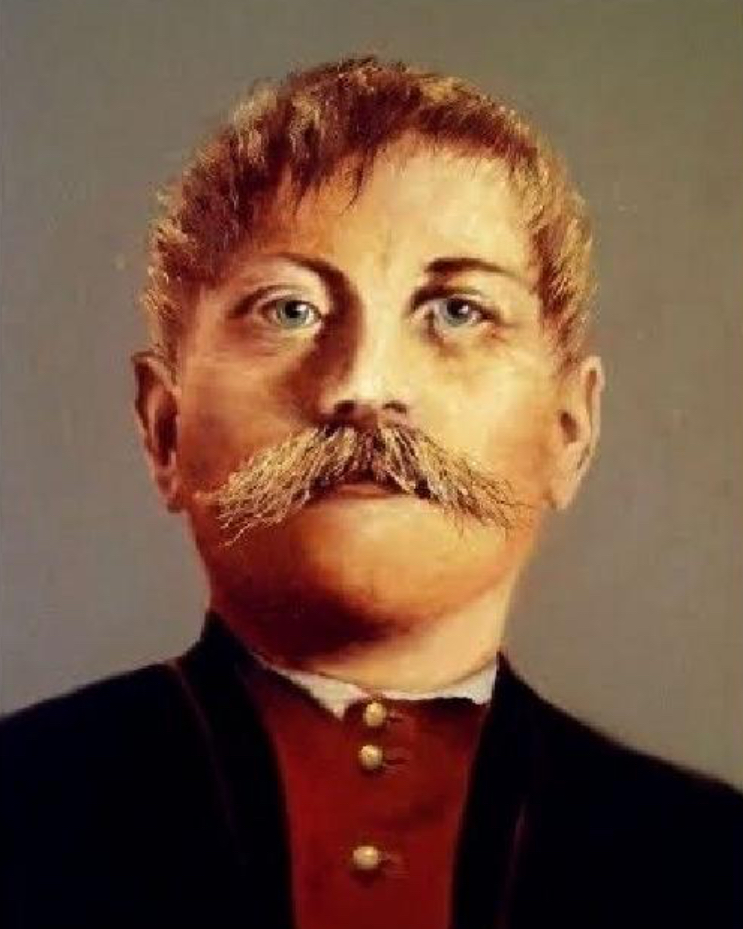

Savanyu Joska. Photo: Painting by Szava Sandor/Wikimedia

Savanyu’s luck ended in 1884 when one of his own men betrayed him by drugging his drink, making it possible for the police to capture him easily. He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

In the end, he spent more than 20 years in prison and was released in 1906 thanks to good behavior and lobbying from various highly placed allies, including the bishop of Vac. A few months later, in 1907, Savanyu took his own life with his favorite revolver due to unbearable rheumatic pain. Savanyu is considered the last famous betyar of the Bakony region. Several caves in the Bakony Mountains, his former alleged hideouts, are named after him.

The betyar culture remains alive in Hungary through songs, dances, and other activities celebrating those swashbuckling characters.

Grave of Savanyu Joska. Photo: Botfai Tibor