Throughout history, the world’s mountain ranges have provided refuge for outlaws. Mountain passes, dense forests, hidden caves, and steep cliffs allowed these figures to ambush travelers, evade authorities, and launch raids before vanishing into the terrain. Many began as ordinary people driven by poverty, injustice, or war into crime, while others remained feared criminals and real nightmares to authorities.

Unlike the largely fictional Robin Hood, the outlaws, whose stories we’ll tell today, were real men who lived and died by the gun and the blade. Their stories often blend daring exploits with violence. Some of them, however, became folk heroes and carved out legends that are still remembered today in popular culture. This week, we revisit the stories of some of those legendary bad guys around the world who chose mountains to hide from authorities. Today, some little-known and famously familiar characters from North America.

The Appalachians: the moonshine kings

In America, the outlaws weren’t always robbing travelers. Sometimes, they were just trying to sell a product the government wanted to tax.

Lewis Redmond, the 19th-century King of the Moonshiners, became a hero in the Blue Ridge Mountains after he killed a revenue agent during a raid. To the federal government, he was a murderer. To the local poor, he was a provider. In 1878, Redmond famously eluded a massive posse for months by using a network of secret mountain cabins and remote hideouts in the “Dark Corners” of South Carolina. He became a regional symbol of resistance against federal authority.

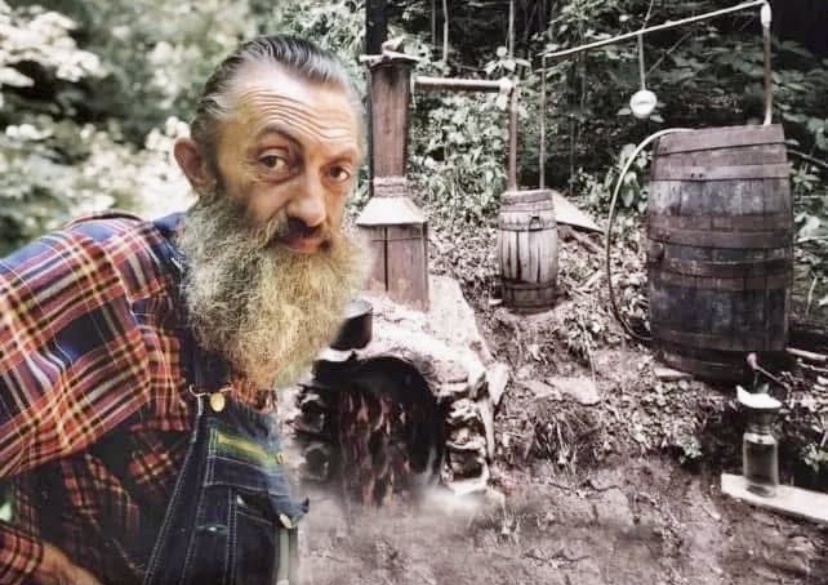

Marvin ‘Popcorn’ Sutton. Photo: Kimberly Wright/Appalachian Americans/Facebook

Fast forward to the 20th century, and we find Marvin “Popcorn” Sutton. A defiant, old-school moonshiner from Tennessee, Sutton didn’t hide from the camera. He didn’t just brew; he bragged. Sutton wrote books, filmed his own life, and basically dared the feds to come knocking.

He thumbed his nose at authorities, using an old school bus on his property to stash over 800 gallons of moonshine and bragging that he traded just three jugs of liquor for his green Ford Fairlane, a car that he later chose as his place of rest to avoid federal prison in 2009.

Popcorn Sutton’s legacy is preserved in the definitive documentary, Popcorn Sutton: A Hell of a Life.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

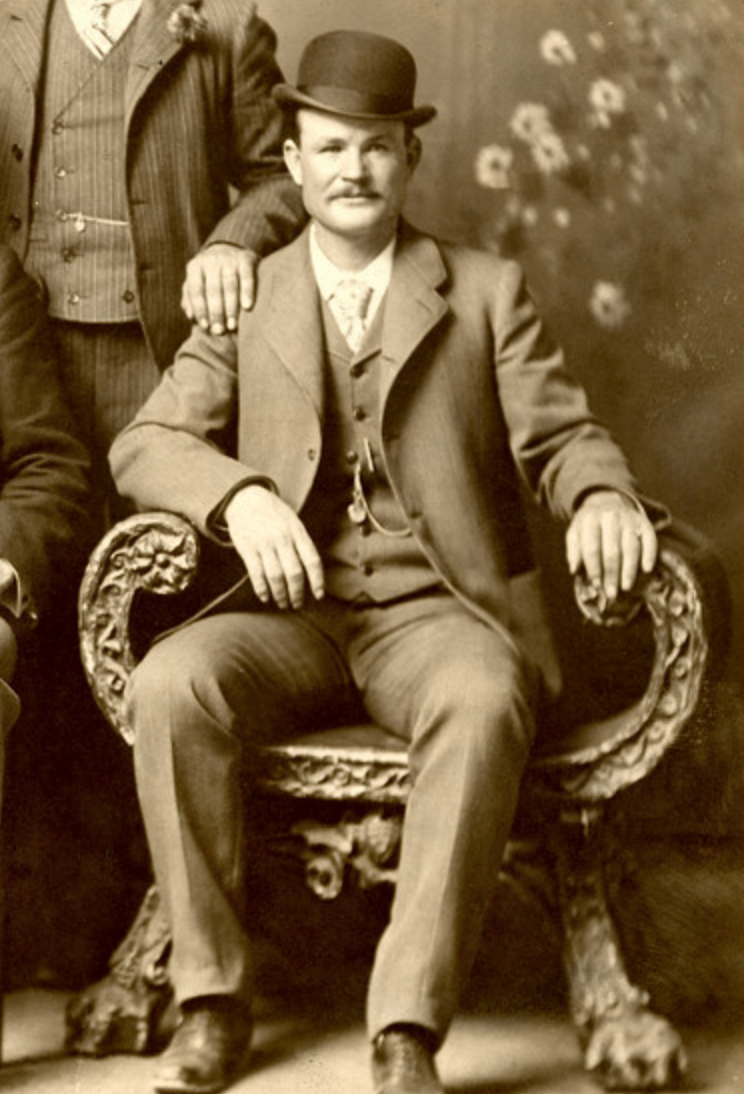

By 1900, Butch Cassidy and his crew weren’t just running from the law — they were running out of room.

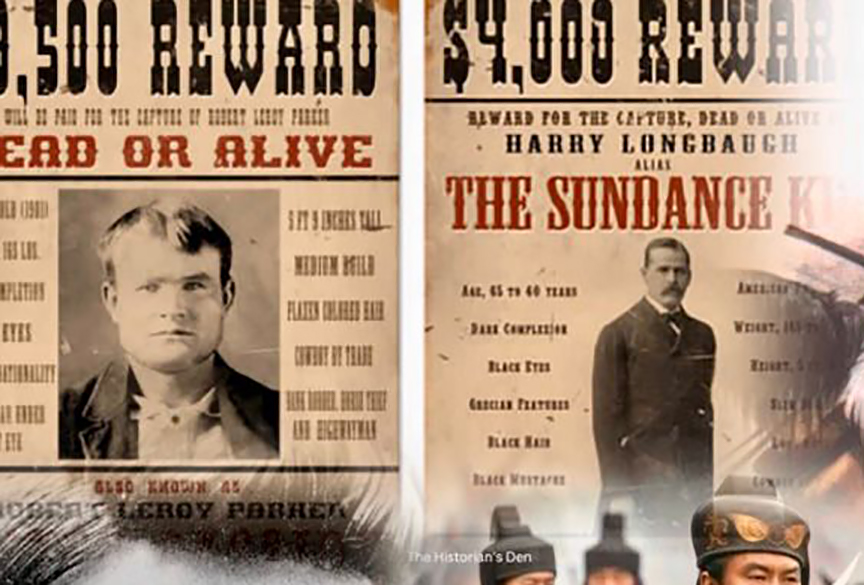

The “civilized” West was closing in, and they knew it. Feeling the heat from the relentless Pinkerton Detective Agency, Butch Cassidy (Robert LeRoy Parker) and the Sundance Kid (Harry Alonzo Longabaugh) decided to vanish entirely. Heading for the southern tip of the globe, in 1901, they stepped off a steamship in Buenos Aires with Sundance’s companion, Etta Place. Here, they began a strange new chapter as ranchers in the Argentinian Andes.

For a minute there, they actually pulled it off. The infamous duo traded bank vaults for cattle stalls and spent a few years living a remarkably quiet life in Cholila. They bought a ranch, built a four-room log cabin, and raised cattle and sheep. They even became well-respected members of the community.

Butch was known for his charisma, and local accounts describe the pair as hardworking neighbors who spoke decent Spanish. At one point, they were so integrated that they even hosted the Governor of Chubut for a night. It’s the kind of detail you couldn’t make up: the most hunted men in the world casually clinking glasses with a state official in the middle of nowhere.

Butch Cassidy. Photo: Wikimedia

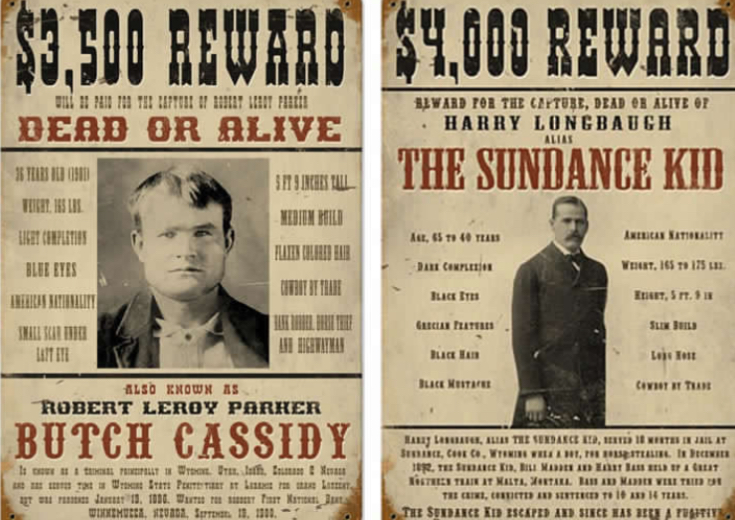

Pinkertons closing in

But let’s be honest, guys like Butch and Sundance weren’t exactly built for a lifetime of ranching. Whether it bored them or they became aware that the Pinkertons were closing in, they eventually sold their land and returned to crime. By 1905, the itch for fast money had come back. They hit a bank in Rio Gallegos and just vanished into the mountains again.

The trail eventually led them into the high air of the Bolivian Andes. The end finally came in 1908. They were in San Vicente, Bolivia, cornered in a small house after a messy payroll heist.

The whole scene was chaos. While local reports described a gunfight and a mercy killing/suicide pact, forensic exhumations in 1991 and subsequent DNA testing proved that the remains in the supposed “outlaw graves” did not match either Butch or Sundance.

The negative DNA results only served to breathe new life into the old ghost stories. As it turns out, the poor guy in the grave was just some German miner called Gustav Zimmer, who basically became a legend by accident.

Wanted dead or alive. Rewards for helping to capture Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Photo: Manquehue.org

While the Bandidos Yanquis are supposed to have died in that Bolivian cabin, the lack of identified remains fueled legends of their survival. His sister, Lula, swore that Butch actually showed up at the family home in 1925 and didn’t die until much later, in 1937. Most historians think she was just trying to keep some family secret alive, but it definitely breathes life into the mystery.

So, did they die in that shootout or retire to a quiet life in the States? Honestly, we’ll probably never know for sure, and that’s exactly how Butch would’ve wanted it.

The Sierra Madre of Mexico and Pancho Villa

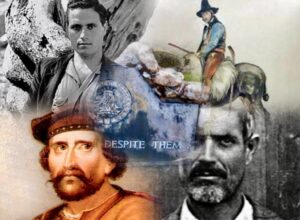

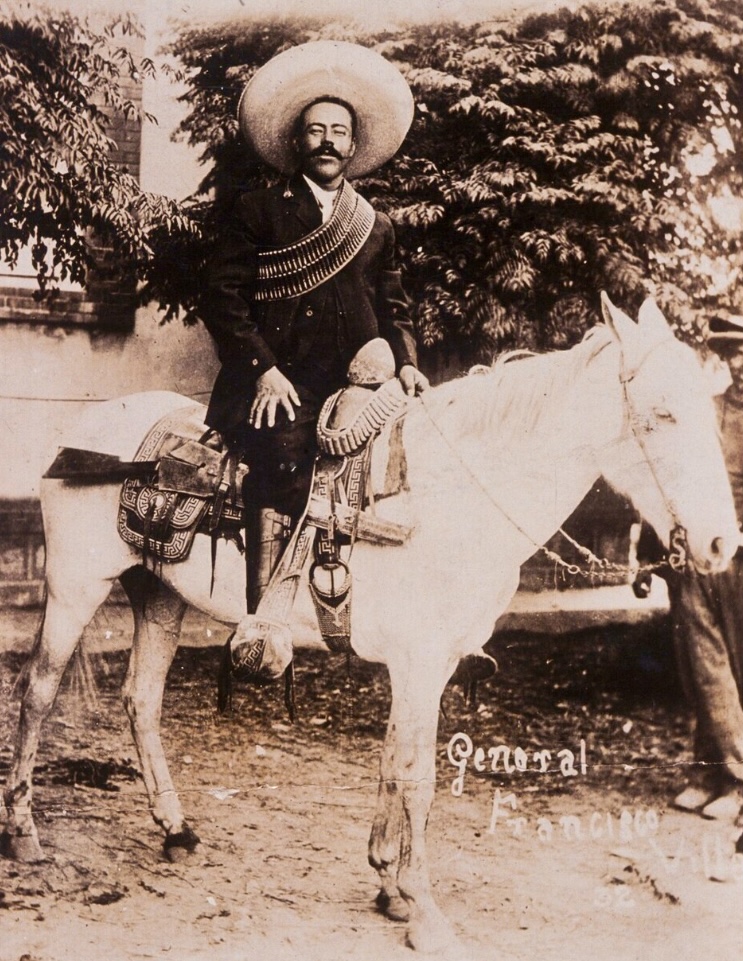

Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa passed much of his early adulthood as a mountain bandit in the harsh Sierra Madre Occidental of Durango and Chihuahua in Mexico.

In 1894, at age 16, after shooting a hacienda owner who had allegedly assaulted his sister, Pancho Villa fled to the mountains. There, he survived as a fugitive, using aliases (first “Arango,” later “Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa”), and joined or led groups of cattle rustlers and robbers. Sometimes, they attacked wealthy haciendas.

This outlaw phase spanned from the mid-1890s until 1910, when he allied with the Mexican Revolution under Francisco Madero. Accounts portray him wandering the hills as a thief, sustaining himself through banditry. Authorities branded him as a mere criminal. He faced multiple arrests (such as in 1902 for mule theft and assault) and even had a short forced army stint before deserting.

He spent 15 years playing a deadly game of hide-and-seek with the law until the Revolution gave him a reason to stop running. His bandit experience sharpened the guerrilla skills he later deployed as a revolutionary commander.

Historians highlight how class divisions influenced perceptions: Peasants viewed him as a defender against exploitive landowners, while the elite saw him as a dangerous outlaw. This chapter closed when he redirected his talents into the revolution, eventually leading the Division del Norte during the Revolution.

Pancho Villa on horseback. Photo: D.W. Hoffman