Throughout history, the world’s mountain ranges have provided refuge for outlaws. Mountain passes, hidden caves, and steep cliffs allowed these figures to ambush travelers, evade authorities, and launch raids before vanishing into the terrain. Many began as ordinary people driven by poverty, injustice, or war into a life of crime.

Unlike the largely fictional Robin Hood, the outlaws whose stories we’ll tell today were real men who lived and died by the gun and the blade. Some of them became folk heroes and carved legends that are still remembered today in popular culture. This week, we revisit the stories of some of those legendary bad guys who chose mountains to hide from the authorities. Today: Eastern European outlaws.

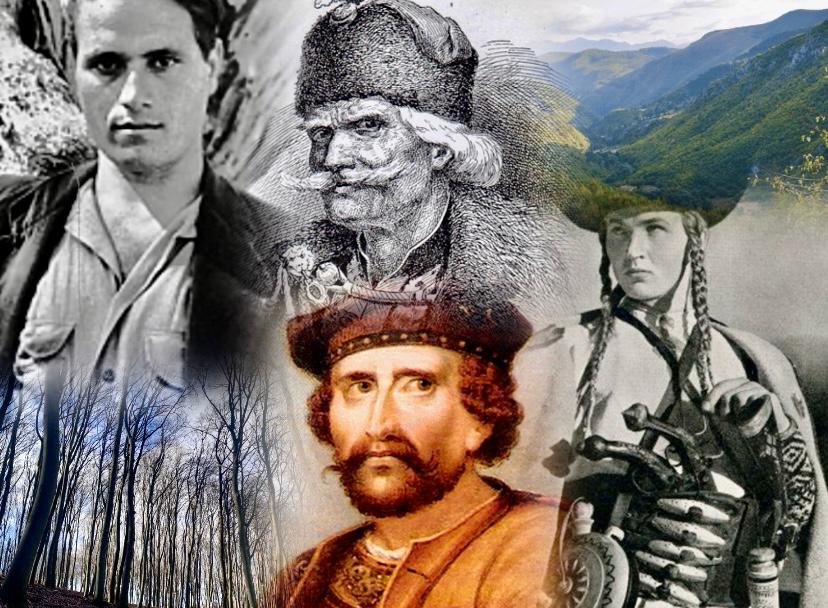

The Balkans: hajduks as freedom fighters

In the Balkans, what is the line between a bandit and a patriot? Well, practically nothing.

Under Ottoman rule, the hajduks used the Rhodope and Dinaric Alps to wage a centuries-long guerrilla war. Imagine a hundred outlaws hiding in the crags, led by a single harambasa (leader). They didn’t just hide. They struck fast and disappeared, hitting Ottoman officials, wealthy Turks, and caravans. They punished oppressors, avenged Christian communities, and shared spoils with supportive villagers who offered shelter and intelligence.

This bond cast hajduks as folk guardians, romanticized in ballads as Balkan Robin Hoods, resisting foreign domination.

Starina Novak. Photo: Wikimedia. Drawing: Uros Predic

Starina Novak of Serbia

In the 16th century, Starina Novak operated across the Balkan Mountains and the Timok Valley. This Serbian hajduk, celebrated in epic poetry, shared loot with the villagers who hid him. One of his craziest stories involves him sneaking right into an Ottoman camp to free prisoners.

By the 19th century, that old hajduk spirit had turned into a full-blown revolution. In eastern Serbia’s highlands, Hajduk Veljko (born around 1780) rose from outlaw to vojvoda (warlord) during the First Serbian Uprising. He led daring raids, culminating in a heroic 1813 stand at Negotin. Here, he and a few men held off massive Ottoman forces to aid Serbia’s independence bid, dying gloriously in battle.

Starina Novak, and tennis player Novak Djokovic, on a mural. Photo: deroks22/Instagram

Petko Kiryakov of Bulgaria

Bulgaria has its own legends, too. Take Petko Kiryakov. He was active in the Rhodope Mountains. Born in 1844 (in what is now Greece), he didn’t start out as a rebel. He was just a guy looking for revenge after his wife was attacked.

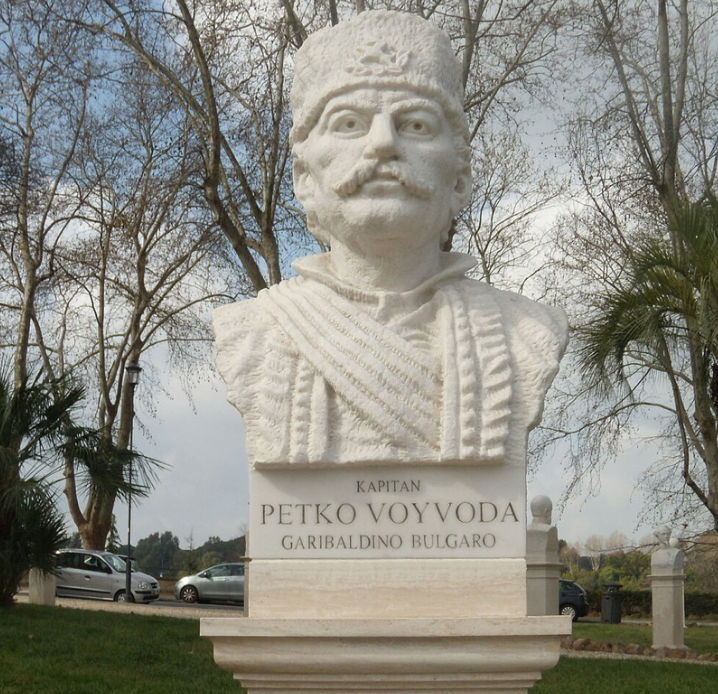

Eventually, he led 1860s guerrilla bands harassing garrisons and freeing villages. He even met Giuseppe Garibaldi and joined the struggle for Italian unification. During the Russo-Turkish War, he once saved a besieged village by having the locals build a straw dummy, hoist it onto the church belfry, and ring the bells like mad. The approaching Ottoman troops, thinking the village was heavily fortified, fled without firing a shot. Petko died in 1900 as a revered revolutionary, familiarly known as Petko Voyvoda.

Petko Voyvoda’s bust at the Janiculum, Rome, Italy. Photo: Amaunet via Wikimedia

Petar Karposh of Macedonia

Petar Karposh was a late 17th-century Hajduk and leader of a short-lived anti-Ottoman uprising in the central Balkans in 1689, known as Karposh’s Rebellion. Born likely as Petar in the Ottoman Sanjak of Skopje (possibly near Kumanovo in present-day North Macedonia), he fled to Romania, worked as a miner, then settled in the Dospat valley of the Rhodope Mountains, near today’s Bulgaria-Greece border. Here, he became notorious for raiding Ottoman forces.

Gathering hajduks and locals amid Holy League wars, he captured towns, built a fortress, and briefly proclaimed a “kingdom” with Austrian support, earning the title King of Kumanovo. Ottoman forces eventually caught up with Karposh, dragged him to Skopje, and executed him on the celebrated Stone Bridge in late November or early December 1689.

Today, North Macedonia remembers Karposh as a folk hero. He features in regional stories as a freedom fighter, blending hajduk banditry with patriotic defiance.

The Carpathians

The Carpathian range was home to the opryshky (Ukraine) and zbojnici (Slovakia/Poland), highland outlaws who lived by the “rob the rich, give to the poor” mantra.

The most famous of them all was the dashing Juraj Janosik. An 18th-century soldier-turned-bandit leader, Janosik became known as the Carpathian Robin Hood. He was known for stopping nobles’ carriages in the fog and seizing gold, though trial records suggest he went out of his way to leave victims unharmed if they weren’t known for exploiting their peasants.

Some historians argue that this whole Robin Hood flavor was heavily romanticized during 19th-century national revivals to create symbols of resistance. Janosik’s end was horrific: In 1713, he was executed by a rib-hook, a meat-hanging device. Janosik is still a national hero in his country.

The handsome Juraj Janosik. Photo: Bystricoviny.sk

In Ukraine’s Hutsul region, Oleksa Dovbush led a similar crusade. Born into a poor family, Dovbush took to the peaks around 1738 with a band of 50 men as part of the longstanding opryshky tradition of resisting feudal oppression.

He famously ambushed a ruthless moneylender on a mountain pass, but instead of taking the money, he seized the debt ledgers and burned them, freeing the local villagers from financial ruin. While legends say he burned ledgers to help the poor, some historical accounts suggest these raids also involved violence or the killing of the lenders. Dovbush was finally betrayed and killed in 1745, and his body was quartered and displayed as a warning.

The ‘abreks’ of the Caucasus

The abreks lived as solitary outlaws or in small bands in the Caucasus Mountains, and frequently acted against Russian imperial domination.

Zelimkhan Gushmazukaev (sometimes called Kharachoevsky), a Chechen folk hero of the early 20th century, escaped to the mountains after a blood feud and an unjust accusation. For more than a decade, he conducted raids on tsarist officials and troops, distributing spoils to struggling villagers.

While the tsarist administration regarded him merely as a criminal nuisance, the villagers considered Zelimkhan a lone defiant voice against an empire that offered them very little. He evaded capture so effectively that Russian forces deployed thousands of soldiers. Ultimately, betrayal led to his wounding and death in a large-scale ambush in September 1913.

Zelimkhan Gushmazukaev. Photo: Wikipedia